People of Torah

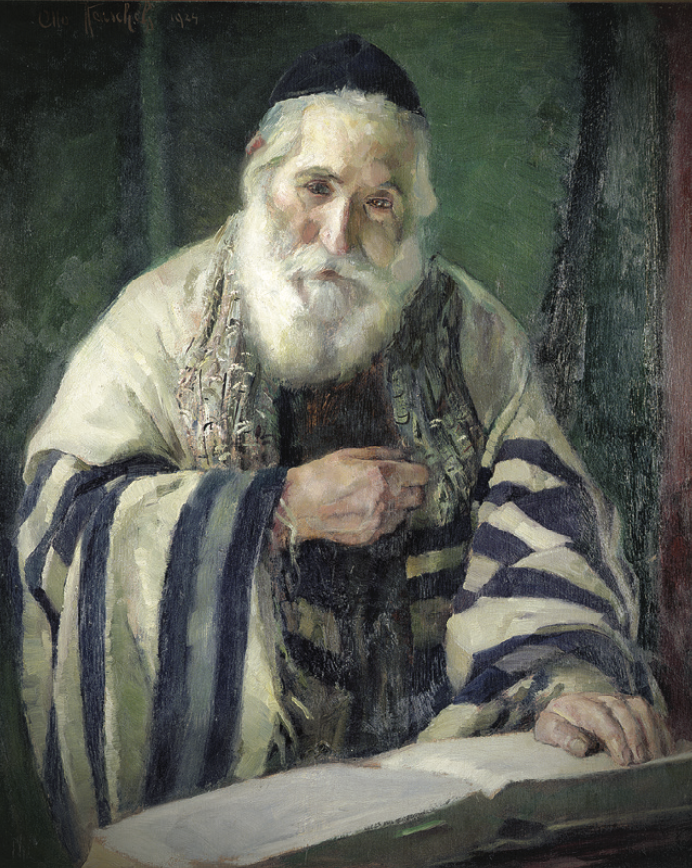

[RABBI READING THE TORAH, 1924, OTTO HERSCHEL—PRIVATE COLLECTION PHOTO ©BONHAMS, LONDON, UK / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES]

Rabbinic Judaism is the mainstream form of Judaism today, preserving the tradition of the Pharisees. After the Second Temple fell in AD 70, leaders called rabbis codified the traditions known as oral Torah into writing and passed on the tradition that Moses had received not only as written but also as oral Torah at Mount Sinai.

The term rabbi primarily means a teacher of Torah. Rabbis study the Talmud as well as Jewish law and worship and may also take courses in modern pastoral subjects such as counseling and preaching. They often lead congregational worship, but their primary roles are as teachers and experts in the law.

The first five books of Moses are known collectively as Torah, or Pentateuch. This is referred to as “written Torah.” The term can also be used more broadly to refer to Jewish writing and tradition, called “oral Torah.” Making a rule or practice stricter than what is explicitly in Torah is often called “building a fence around Torah,” based on Deuteronomy 22:8, to avoid the possibility of transgressing God’s commands.

The entire group of Jewish sacred writings is called the Tanakh, often referred to in English as the Hebrew Bible or Hebrew Scriptures. While the content is essentially equivalent to the Hebrew and Aramaic text of the Protestant Old Testament, the books are divided differently; Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra and Nehemiah, and the 12 Minor Prophets make up one book each, and the books appear in a different order. The Masoretic Text, which dates from c. 800 to 1100, is considered the authoritative text of the Tanakh.

Two major collections of oral Torah into writing exist: the Mishnah, collected in the late second century by Judah ha-Nasi, and the Gemara, a record of commentaries and debates on the Mishnah. Together they are called the Talmud. There are two versions, the Jerusalem Talmud and the Babylonian Talmud.

Rabbis and others interpret the sacred writings through a kind of interpretation called midrash. It focuses mainly on a close examination of the text in light of the tradition of interpretation by previous rabbis. Haggadah is midrashic commentary on Torah that takes the form of storytelling. Much midrash is in this form. Some midrash is halakha, the set of religious laws that explain what counts as carrying out God’s commandments. At the core of halakha are mitzvoth, biblical commandments of behavior—there are traditionally considered to be 613 commandments in Torah. Halakha also includes commentary and discussion on these commandments. One of the best-known examples of halakha is the set of Jewish dietary laws known as kashrut; food conforming to these laws is called kosher.

The synagogue is the primary place of Jewish worship, reading of the Tanakh, study, and prayer. Normal public worship and some other activities require the presence of a minyan, or quorum of 10; in traditional Judaism this must be 10 men, but in Reform and Conservative Judaism women may be counted.

Today Jewish people fall into three major geographical divisions. Ashkenazi Jews descend from those who migrated first to the Holy Roman Empire (modern Germany) and then to Eastern Europe. (Yiddish, their traditional language, combines Germanic and Hebrew influences.) Sephardic Jews descend from those who migrated to Spain and Portugal. Mizrahi Jews are considered to be those from the Middle East, although the exact application of the term is controversial.

Four major divisions of belief and practice exist within rabbinic Judaism. Orthodox Jews are the most traditional branch, believing that Torah and Talmud have been faithfully transmitted and should be observed strictly. One well-known subdivision is Hasidic Judaism, which arose in the 1700s in Poland and spread to the United States. It combines ecstatic kabbalah teachings (see p. 21), Orthodox practices, and Eastern European cultural customs.

Reform Judaism developed in the early to mid-nineteenth century with an emphasis on ethical principles and on God’s continuing revelation, similar to that found in Protestant liberalism of the time. Conservative Judaism developed after Reform to create a middle ground; its adherents maintain generally traditional practices but are also open to adaptation. Reconstructionist Judaism is a branch of the Conservative movement that broke away in the mid-twentieth century. It values traditional practices as expressions of Jewish culture.

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Next articles

Larger than life

Christian thinkers Adopted Jewish symbols—but mistrusted their sources

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate