Larger than life

[Page from the mishneh torah, systematic code of Jewish law written by Maimonides (1135–1204) in 1180, c.1351 (vellum)—Bridgeman images]

Jerusalem the golden,

With milk and honey blest;

Beneath your contemplation

Sink heart and voice oppressed.

We hear these words today and think of cathedral choirs. But the original Latin dates back to the twelfth century—part of a rich heritage of medieval Christian prayer drawing on Jewish imagery.

Medieval Christians celebrated the Old Testament as part of their Scripture, reading it allegorically and applying it richly to their own experience. When under attack by Vikings or Magyars or Arabs, Christians prayed penitential psalms and confessed sins that they believed were bringing God’s judgment, while asking God to smite their enemies just as he smote the enemies of ancient Israel. Bishops annointed Christian kings with holy oil like Old Testament rulers. Images of ancient Hebrew kings and prophets adorned churches. Christians sang songs of longing for Jerusalem. At the same time, Christians had relatively few dealings with actual Jews, and thus changes taking place within Jewish communities went unseen by Christians for centuries.

“Slay them not”

Initially Jews enjoyed essentially the same status under Christian emperors as under pagan ones. This changed around 500 when Eastern Roman emperors began persecuting Jews, pagans, and heretical Christians. In the seventh century, Emperor Heraclius attempted to force Jews to convert, in part due to allegations of Jewish collaboration with Persian invaders and atrocities against Christian prisoners. At around the same time in the West, Visigothic kings of Spain enacted harsh legislation to force Jews to convert; but Pope Gregory the Great (540–604) intervened.

For the most part, though, both Christians and Muslims in the early Middle Ages allowed Jews to live in peace as long as they submitted and paid taxes. For Muslims this policy was prescribed by Islamic law. For Western Christians the theology of St. Augustine provided the rationale for tolerating Jews while praying for their conversion. Augustine argued that Jews were indispensable witnesses to the truth of the gospel, citing Psalm 59:11: “Do not kill them, so that my people will not forget.”

After 1000 Western Europe began a series of dramatic changes. A growing population, fueled by agricultural innovations, led to reborn urban life and trade. New universities developed around cathedrals; bishops and monarchs alike sought trained bureaucrats to govern an increasingly complex society. These new institutions used a new intellectual method, scholasticism, which asked critical questions and sought to systematize available knowledge.

Scholasticism led to a more active, dynamic engagement with non-Christian thought, both ancient and contemporary. Muslims and Jews living in the Islamic world introduced Christians to texts by Aristotle they had previously not known, along with commentaries on these texts by Jewish and Islamic writers. Christian scholars sought out Jews and learned Hebrew from them. They became aware of the massive body of rabbinic literature produced since the paths of the two traditions diverged centuries earlier. From the thirteenth century on, the “mendicant (begging) orders”—Franciscans and Dominicans—pioneered this work. These religious communities both focused on engaging in active ministry in the world and evangelizing both non-Christians and lapsed ones.

But this explosion of intellectual and cultural creativity had another side. Traditionally church officials had restrained civil authorities while maintaining their right to defend “true faith” and godly order. But now the church began taking a more active role in putting heretics on trial, handing them over to secular authorities for execution—and justifying this in Old Testament terms. Pope Gregory VII (1015–1085) frequently cited Jeremiah’s prophetic authority over nations and kings to “pluck up and tear down” to support papal actions. Medieval theologians spoke routinely of the gospel as the “New Law.”

Western Christian thought in the High Middle Ages increasingly identified the newly dominant, confident Catholic Church with the heavenly Jerusalem, hoping to capture some fragments of its glory even in this world of sorrow. The most dramatic expression of this was the Crusades—recovering the literal Jerusalem from the Muslims. The long-standing Christian tradition of pilgrimage to Jerusalem ignited crusading fervor, and this fervor had devastating side effects for Jewish populations through which the Crusaders passed.

Killing Jews on the way to fight Muslims had already become a reality in eleventh-century Spain. Pope Alexander II explicitly condemned these attacks and praised Spanish bishops for protecting Jews. Others followed suit. Some, however, offered protection only on the condition that Jews accept baptism, leading the Jews of Worms to kill themselves rather than abandon their faith or fall into the hands of the Crusaders.

In the twelfth century, Peter the Venerable advocated confiscation of Jewish property to fund the Crusades:

The evil, blaspheming Jews, far worse than Saracens, not at a distance, but in our midst, so freely and audaciously blaspheme, trample underfoot, deface with impunity Christ and all Christian mysteries. . . . Let their life be safeguarded, let their money be taken away.

Bernard of Clairvaux, in contrast, while a passionate advocate of the Crusades, reaffirmed the official view:

It is noble of you to wish to go forth against the Ishmaelites; still, whoever touches a Jew so as to lay hands on his life, does something as sinful as if he laid hands on Jesus himself!

Inquisition and expulsion

Mendicants often came from the rising middle classes, those most likely to compete economically with Jews. They also first identified for Christians the centrality of the Talmud to Jewish life and thought. These friars studied Judaism not just as ancient tradition but as a living rival to Christianity. And they were horrified.

Friars discovered Jewish arguments at odds with traditional Christian interpretations. Andrew of St. Victor (d. 1175) had already caused a stir by accepting, as the true literal sense of the text, the interpretation that Isaiah 7 refers to events in Isaiah’s own time. Nicholas of Lyra (c. 1270–1339), who knew Hebrew and engaged extensively with Jewish scholars, identified this as the literal-historical sense and posited a second, more clearly Christian “literal-prophetic” sense.

As the friars laid claim to the literal sense of Scripture, they became increasingly aware that the Jews had their own nonliteral traditions of interpretation. This led the friars to focus on the Talmud and its alleged corruption of Scripture:

They, displaying no shame for their guilt nor reverence for the honor of the Christian Faith, throw away and despise the Law of Moses and the prophets, and follow some tradition of their elders. . . . In it are found blasphemies against God and His Christ. . . . They fear that if the forbidden truth, which is found in the Law and the Prophets, be understood, and the testimony concerning the only-begotten Son of God, that he appeared in the flesh, be furnished, these would be converted to the Faith and humbly return to their Redeemer.

This had serious consequences because the Inquisition had no jurisdiction over non-Christians, but considered Christians who chose to become Jewish as apostates. Jews who sheltered such people or were suspected of proselytizing could be prosecuted. Then in 1232, in the southern French town of Montpellier, some Jewish opponents of Maimonides (see p. 37) allegedly asked inquisitors for help: “Now, while you are exterminating the heretics among you, exterminate our heresies as well and order the burning of these books.” We don’t know whether anyone burned Maimonides’s books. But Christian authorities did burn the Talmud on a number of occasions throughout the later Middle Ages.

“Perfidious Jews”

Hostility to the Talmud became the central pillar of elite anti-Judaism. Christians interpreted Talmudic accounts of a heretical “Yeshu” as blasphemy against Jesus and criticized passages extolling Jewish superiority and encouraging hostility to gentiles. Allegedly the Talmud twisted Jews’ minds so they could not see evidence for Christian claims in Jewish Scripture. The Talmud’s focus on this life seemed to promote greed and worldliness; in contrast, Christian Scripture was seen as pointing people to the life of the world to come.

Medieval Christians felt that allowing Jews to exist among Christians was already an act of extreme forbearance. The church’s Good Friday prayers included a petition for the “perfidious Jews,” that God would have mercy and turn their hearts—a conversion believed to be one of the signs of the End. But now the audacity of the Jews in developing their own traditions furnished a reason to withdraw toleration.

Increasingly authoritative popes led the charge. Innocent IV argued that he had “authority not only over Christians but also over all infidels.” In the course of the thirteenth century, popes and mendicants worked together to burn copies of the Talmud, force Jews to listen to Christian sermons aimed at their conversion, and compel them to debate Christian scholars.

Catalan friar Ramon Llull (c. 1232–c. 1315) tried to educate Jews to make them convert and evangelize other Jews. Jews who refused to go along could be expelled—and were. Jews were most secure from expulsion in Rome itself, but from the thirteenth century on, Jews in Rome had to present each new pope with a Torah scroll, which he accepted with the declaration that Christians accepted the Jewish Scriptures but not Jewish interpretations.

By focusing hostility on the Talmud, Christians could persecute Jews while claiming still to respect Jewish Scripture and the original Jewish Law. Calling the Talmud “human tradition” gave Christians an effective way of dealing with the fundamental problem posed by the continued resistance of Jews to Christianity.

Pressure redirected

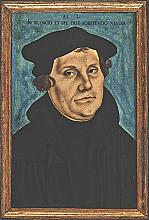

This hostility formed an important backdrop to the Reformation. In 1509 Dominican friar Johannes Pfefferkorn received a mandate from Emperor Maximilian to destroy all Jewish books opposing Christianity. A convert from Judaism, Pfefferkorn was not, by the standards of his time, a particularly ferocious persecutor, but he agreed with the emperor. However, he ran into opposition from humanist scholar Johannes Reuchlin. An enthusiast for Christian Kabbalah, Reuchlin had published a Hebrew grammar so Christians could teach themselves the language of the Old Testament without consulting Jews.

Reuchlin won, for the time being, but this didn’t stop attempts to confiscate the Talmud. And many observers saw in the conflict between Luther and Tetzel a few years later a second round of the Reuchlin debate. Protestants believed medieval Catholics had fallen into exactly the same trap as Jews: replacing Scripture with human tradition. Yet at the same time, they continued enthusiastically to pursue Hebrew learning (Luther’s own scholarly emphasis was the Old Testament) and, even more than their medieval predecessors, appealed to the Hebrew text and Jewish commentaries. Calvin focused so heavily on what he took as the “literal” sense of the Old Testament, often challenging traditional Christian interpretations, that other reformers called him a “Judaizer.”

By relocating conflict between true revelation and false human tradition within Christianity, the Protestants took pressure off the Jews and made them just one more example of a people who had substituted human tradition for a proper understanding of God’s Word. Catholics controlled powerful nations, armies, and fleets; Jews, in contrast, posed little real threat.

In Reformed Christianity in particular, writings of Jewish rabbis filled the shelves of scholars, and the Old Testament, no less than the New, was seen as a revelation of Christ and a guide to the proper way to live and order society. Reformed rulers saw themselves in the mold of kings David and Josiah; this reached almost messianic proportions when Frederick V of the Palatinate (1596–1632) was called a new David delivering Protestants from Catholic oppression. Perhaps unsurprisingly the radical apocalyptic Calvinists of Cromwell’s England readmitted Jews after centuries of exclusion and the Protestant Netherlands, predominantly Calvinist, gave shelter to Jews driven out of Catholic Spain.

But because of the central role of Jews in the Christian story, it was hard, and remains hard, for all these Christians to look at Jews without seeing larger-than-life symbols. The tragedy of medieval encounters between Christians and Jews is that when Christians began engaging more seriously with Judaism, it accentuated rather than ameliorated their hostility. The turn toward a “literal” Jerusalem, whether in exegesis or in Crusade, was also a turn against real Jews. C H

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is a Christian History contributing editor.Next articles

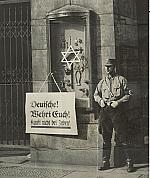

“Never shall I forget”

From 1933 to 1945, Germans—some of them Christians—murdered six million Jews

Chris GehrzSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate