Kabbalah

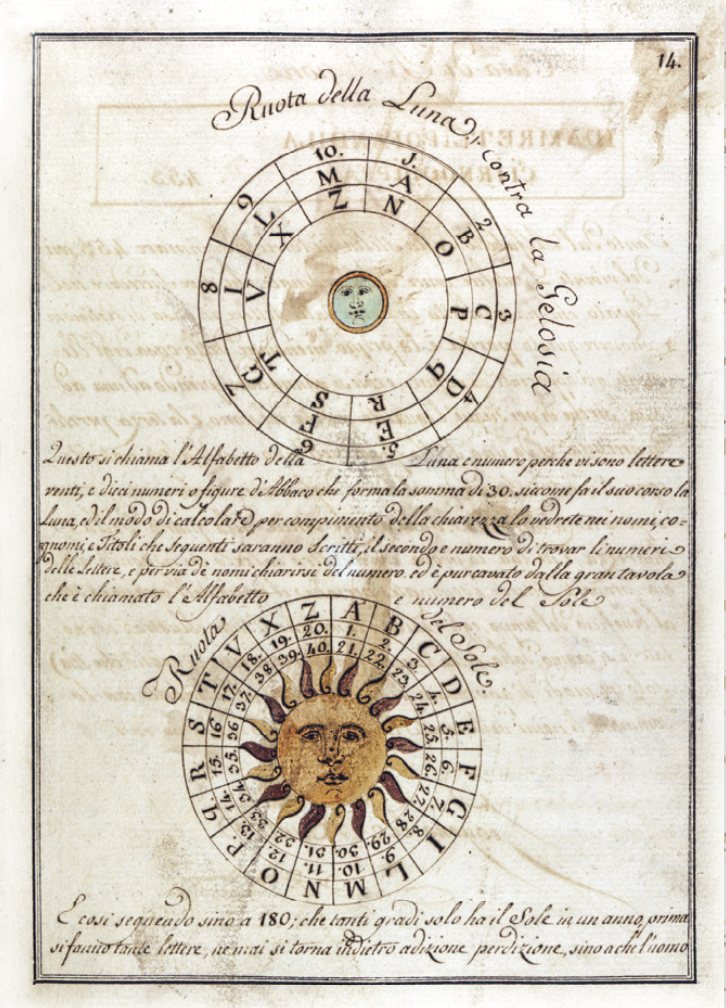

[A HANDWRITTEN PAGE BY GIOVANNI PICO DELLA MIRANDOLA (1463–1494) (JEAN PIC DE LA MIRANDOLE)—IN COMPENDIUM ARTIS MAGNAE ET CABALISTICAE, 17TH CENTURY—© GIANCARLO COSTA / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES]

The desire to experience the presence of or be unified with God is as old as religion itself, and we often give it the name “mysticism.” In the Jewish context, this took on different forms as Jewish communities migrated east and west following the destruction of the Second Temple. However, a new and influential form of mysticism emerged in the mid-twelfth century in Languedoc, a land bordering the Iberian Peninsula in the south, the Kingdom of France in the north, and stretching toward northern Italy in the east. It became known as Kabbalah.

Where did Kabbalah come from? Perhaps it arose in the meeting of cultures. Jews migrated to this area from communities in Ashkenaz (the Talmudic term for the area now known as Germany), where they had developed a form of pietistic mysticism partly based on the adoption of Christian monastic practices. These Jews were joined by others fleeing from fundamentalist Islam in Andalusia, a region of Spain.

They brought with them philosophical works and concepts unknown in the Christian world; new understandings of the relationship between God and humankind began to develop. Basing their activity on anonymous works such as the Book of Creation (Sefer Yetzirah) and the Book of Clarity (Sefer ha-Bahir), along with new interpretations of Jewish rituals, small groups of masters and disciples engaged in mystical practices designed to bring them into close proximity with emanations they believed to be proceeding from the divine. They hoped through their practice to restore unity in the divine world and hasten the final redemption.

Explanations for exile

In the late twelfth century, these oral teachings began to be put into writing, catalyzing a period of intense creativity that peaked with what would eventually become known as the Zohar (Book of Splendor). Written in Aramaic and attributed to a second-century sage, Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai, different authors in Castile (modern-day Spain) actually composed it over a period from the mid-thirteenth century to the fourteenth.

These Kabbalistic compositions mostly focus on the 10 sefirot—considered to be revealed attributes or emanations of the divine emerging from within the Ein Sof (unknowable infinite) and drawing down the divine so that it flows out into creation. The Kabbalist aspires to unite with the last of these emanations, called Malchut (kingship) or Shechina (the feminine aspect of the divine). Kabbalists believe that human history mirrors the sefirotic world and that the current Jewish exile is a result of a break between the top nine sefirot and the tenth sefirah, making the divine unable to flow into creation. They maintain that strict adherence to the 613 commandments (see p. 11) with right intention can help repair the break and bring about final redemption both in the material and the divine worlds.

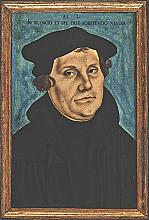

Christian interest in these esoteric teachings started with Ramon Llull (c. 1232–1316), a late thirteenth-century polymath who worked and wrote tirelessly to convert all non-Christians. Llull thought that Kabbalistic teachings about the sefirot were so close to Christian teachings about the inner workings of the Trinity that Kabbalists could be easily convinced to accept Christian truth.

Llull’s quest was unsuccessful, but during the Renaissance, humanists such as Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) focused on Kabbalah’s supposed antiquity and argued that these ancient teachings revealed the truth of Christianity. They particularly focused on the first three divine emanations—Keter (crown), Hochma (wisdom), and Binah (understanding)—which they understood as representing the Trinity.

Mirandola used thousands of folios of Kabbalistic texts translated for him into Latin by a Jewish convert, Flavius Mithridates (1450–1489). Many Christian Kabbalists followed him, such as Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1631–1689) in the seventeenth century, who made Latin translations of many of the central medieval works of Jewish Kabbalah.

While the Christian world adopted and adapted Kabbalistic teachings for its own purposes, particularly after the advent of printing, Jewish Kabbalah had a renaissance of its own. The establishment of an important center of Kabbalistic thought in sixteenth-century Safed, then part of the Ottoman Empire, resulted in its spreading around the world.

By Harvey J. Hames

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Harvey J. Hames, professor of history, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, IsraelNext articles

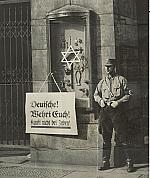

“Never shall I forget”

From 1933 to 1945, Germans—some of them Christians—murdered six million Jews

Chris GehrzA land called holy

The founding of the State of Israel opened new questions for Jewish-Christian relations

Robert O. SmithSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate