The greatest missionary you’ve never heard of?

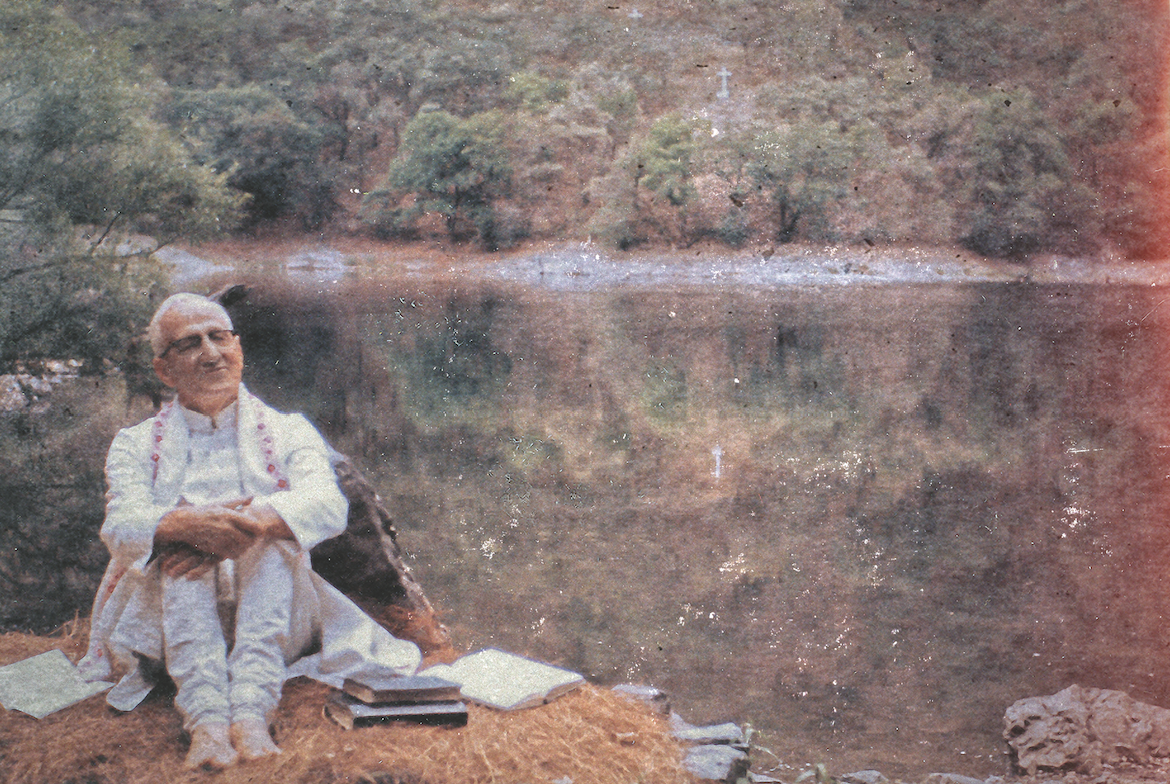

[E. Stanley Jones at Panna Lake Sat Tal, India. B.L. Fisher Library Archives, Asbury Theological Seminary]

In 1938 TIME magazine named him “the world’s greatest missionary evangelist.” Today when we hear these words we might think of Billy Graham or recent famous TV preachers, or evangelists of past centuries such as George Whitefield, Billy Sunday, and Dwight Moody. But after Sunday, and before Graham, E. Stanley Jones (1884–1973) dominated the scene.

Swept off his feet

Born outside Baltimore in 1884, Jones felt his childhood was not particularly notable, and he hesitated to talk about it. Nonetheless Jones’s mother and grandfather influenced his early religious experiences. At 15 years old, he first encountered God, but it did not sustain him. Two years later, in 1901, he responded to an evangelistic invitation in his local church. He rejoiced, “I’ve got Him,” meaning that now he did not have an “it” but a Him. He had Jesus and Jesus had him.

Soon after, Jones met Henry Clay Morrison (1857–1942)—soon to be president of Asbury College in Wilmore, Kentucky—while Morrison was holding meetings in a Methodist church in Baltimore. Jones was impressed. If he could learn to preach like that at Asbury, then to Asbury he would go. Probably in 1903, but perhaps as late as 1905, the first Asbury Revival struck the campus and then the entire town of Wilmore.

There Jones recorded that he experienced the filling of the Holy Spirit and became a self-proclaimed “holiness preacher.” He and four or five of his classmates were praying in one of their rooms when something happened, without provocation, that would change his life. As they prayed he felt the Holy Spirit sweep them off their feet and fill them all. It seemed to him a new Pentecost and would become one of the most sacred and formative moments in his life.

Equally significant was his call to missions. The Student Volunteer Movement invited him to speak on missions in Africa; he prayed, “Now, Lord, I don’t want to go into that room to give a missionary address. I want you to give me a missionary.” He began by saying someone would go to the mission field from that place. Little did he know he would be the one.

Early on Jones felt called to Africa. An excellent student, he had several options and opportunities upon graduation. He received an invitation to teach at Asbury (which he did, briefly); he also received a letter from a trusted friend to consider being an evangelist in America. Then he received a letter from the Methodist Mission Board offering to send him to India. Jones prayed and heard an unmistakable voice saying: “It’s India.” From that moment it was settled. He would rely on hearing God through this inner voice for guidance and direction for the rest of his life.

On November 3, 1907, Jones left on the S.S. Victoria bound for England, with no seminary training and little money. From England he sailed on to India, arriving in Bombay (Mumbai) and then by rail north to Lucknow. He was 23. Jones was ordained and then appointed to the English-speaking Lal Bagh Methodist Church. For the next eight years (1907–1915), he would be consumed by what he later described as “self-striving, self-effort, and eventual collapse from wearing too many hats.”

Meanwhile Mabel Lossing (1878–1978) had sailed out of New York in 1904 with 400 pounds of books. She took little else with her except for a reputation as a serious-minded Christian, a successful teacher, and a linguist. She arrived in Bombay at age 26. At the end of 1908, she was sent to the Isabella Thoburn College in Lucknow to fill in for a missionary teacher who had suffered a nervous breakdown. Lossing began attending the Lal Bagh Church and soon met Jones. She became the organist; Jones thought that she was the “sweetest girl in the world.”

Determined duo

Jones and Lossing were married in Bombay in February 1911 and moved to Sitapur where there was no electricity and no running water. For the next 62 years, they labored in and out of India—Mabel with her schools and Stanley with his work as a missionary/evangelist. Mabel Lossing Jones became a driving force behind her husband as he embraced a global preaching and teaching schedule. They were a remarkable couple, both called by God and each determined to follow him.

Even as she supported Stanley, Mabel had her own vision: a primary school for boys run completely by women. It was unheard of for women to teach boys in that society, but she did not think that men took the task seriously enough. The school far exceeded expectations. Stanley boasted it was exemplary (see pp. 17–20). Even Mahatma Gandhi, who corresponded with Stanley and Mabel, commended its success.

By the end of 1911, Jones was preaching more regularly and beginning to see significant results. His Indian friends said that of the 330 million Hindu gods, not one is called loving. Jones shared the message of his God of love. Eventually, however, his responsibilities began to take their toll. He was preaching throughout India and neighboring countries, often warding off diseases, snakes, scorpions, and the summer heat. Despite running ragged, he believed that he could do it all out of his own strength.

Mabel also weathered his long absences, and Stanley spoke of her inner strength fondly: “Few women would have been equipped for such an adjustment and sacrifice.” Eunice, their only child, was born on April 29, 1914. Her father missed her birth but arrived soon after. When Mabel was 100, she was asked about her happiest memory. She murmured, “The day Stanley came home after Eunice’s birth and held me in his arms.”

However, Stanley increasingly spent more time apart from Mabel and Eunice. World War I broke out in June 1914, and soon Great Britain declared war on Germany, bringing food shortages and soaring prices. Then in October 1914, Jones was taken to Lucknow Hospital with a ruptured appendix. He was weary.

“Why don’t you come to us?”

Jones’s early ministry among the outcastes had been nearly all consuming. But he also went in the evenings to a tennis club of Indian officials and lawyers. Early on a Hindu judge asked, “Why do you go to the outcastes? Why don’t you come to us?” Jones had assumed that the upper castes did not want him as a missionary, but the judge informed Jones that they did indeed want him, provided he came “the right way.” That phrase remained in his mind and heart.

The call to the upper castes seemed right, but how could he manage with all of his other responsibilities? He faced a spiritual crisis. “Physical sag brought spiritual sag,” he later wrote. His body was no longer resisting disease, and his nervous collapses continued. Sometimes while preaching his mind would go blank, and he would have to sit down, embarrassed and perplexed. Eventually he and Mabel were ordered to go to America on an early furlough.

Jones spent the furlough year (1916–1917) studying and making missionary addresses. Forever feeling as if he lacked the necessary educational training to fulfill his calling, he studied at Princeton Seminary where he met Toyohiko Kagawa, a fellow student who would become a leader in Japanese Christianity. Twenty-five years later their deep and lasting friendship would nearly avert war with Japan.

The Joneses arrived back in India in April 1917. Jones was still not well and went to the mountains to recuperate. He needed healing—in body, mind, and spirit. In this dark hour, he felt led by the Holy Spirit to the Central Methodist Church in Lucknow.

In the back of the church, he knelt in prayer, not for himself, but for others, and felt that God said to him: “Are you yourself ready for the work to which I have called you?” He replied, “No, Lord, I’m done for. I’ve reached the end of my resources and I can’t go on.

The Lord replied, “If you’ll turn that problem over to me and not worry about it, I’ll take care of it.” Jones eagerly said, “Lord, I close the bargain right here!” He arose knowing he was well. Years later a marble tablet was put up on the church wall: “Near this spot Stanley Jones knelt a physically broken man and arose a physically well man.”

“Daddy won’t be happy”

Jones could no longer accept old approaches to evangelism that attacked non-Christian faiths. This in part resulted from meeting Gandhi in 1919, beginning a friendship that lasted until Gandhi’s assassination 30 years later (see pp. 24–28). Jones’s ministry took on new meaning as seen in his first book, The Christ of the Indian Road (1925). It sold over a million copies worldwide.

Jones embraced a routine he kept for decades: traveling, preaching to thousands, and organizing Round Table Conferences (see p. 16) where Indian intellectuals sat with him and shared what their religion meant to them. More than half were non-Christians. No one could interrupt or challenge another; Jones would share last. Frequently, at evangelistic meetings in the evenings, many participants became Christians.

Jones also began his ashram movement (see pp. 12–15) at Sat Tal in the Himalayan foothills, leading an experience he had learned from Gandhi and Indian poet Tagore. The difference was that Jesus, not a guru, was the teacher directing the ashram.

In 1928 Jones went to Kansas City as a delegate to the Methodist General Conference. The conference reached an impasse on electing a bishop; much to Jones’s chagrin, they broke it by electing him. When Mabel found out, she put a sheet over her head. Fourteen-year-old Eunice wrote 14 reasons she did not want her father to be a bishop; the first was that she “loved their home in Sitapur” and the last was “Daddy won’t be happy.”

Unbeknownst to them Jones could not sleep that night. The next evening when he took his seat among the bishops his inner voice said, “Now is the time to resign.” He thanked the conference for the honor, told them that he was called to be a missionary evangelist and—much to the discomfort and even animosity of some—resigned. Eunice and Mabel were relieved.

Yet, even in India, Mabel continued to experience loneliness as Stanley was gone much of the time. Her realization that her own calling to “her boys” was just as strong as his to preach the Word sustained her. In 1930 the two spent only 10 days together. (She once said she would rather spend two weeks with Stanley Jones than an entire year with any other man.)

In March of 1930, Gandhi began his famous Salt March protesting the British monopoly on salt. He vowed not to return to his ashram until India was free and independent. Jones visited the Indian National Congress at Allahabad and met Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, calling him “a man of deep sincerity but of very radical views.” Jones was skeptical. He vowed, “I have to speak to India, and I must know what India is thinking.” At this point he was also traveling extensively in the Far East; he spent time with leaders of China, including Chiang Kai-Shek, who reportedly read from Jones’s devotional books daily. One sojourn through Russia led Jones to investigate communism.

He was increasingly identifying the central message of the Gospels as the Kingdom of God; he wondered if this had anything in common with Marxism. This question consumed him for decades, eventually leading him to write a “Nazareth Manifesto,” in which Jesus, not Karl Marx, is the protagonist. The Kingdom of God for Jones was never just generic world brotherhood; it remained firmly Christ-centered.

Meanwhile Eunice had married missionary Jim Mathews. During World War II, Mabel remained in India with Eunice and Jim while Stanley preached across the United States; Great Britain denied him visas to return to India until after the war, believing that he was too pro-India to be objective regarding British rule.

In 1941 Jones and his friends at the Japanese Embassy, prompted by Kagawa, asked President Roosevelt to write Emperor Hirohito asking for greater understanding. Roosevelt sent a telegram on December 5, but tragically the emperor did not receive it until after the Pearl Harbor attack. A counsel to the emperor later said that if the emperor had received the telegram a day sooner, he would have stopped the attack.

Ten-year plan

When Jones’s visa was finally renewed in 1944 and he could travel home, he decided that for six months of each year he would stay in India. January to April, he would hold evangelistic meetings, and May and June he would be at Sat Tal. Then he would go to the United States, leading ashrams in July and August and then conducting evangelistic campaigns.

In 1946 Mabel left India never to return. Stanley continued his travels, spending his allotted six months in India and six months in the United States and abroad. He also continued to write. In 1954, when Stanley turned 70 and Mabel turned 76, they both officially “retired” from the Methodist Board of Missions. But Stanley made it clear that his “ten-year plan” would be extended for the rest of his life, commenting, “You may retire me as an active missionary of the Board of Missions, but you cannot retire me as a missionary.” Mabel concurred.

Jones expanded his reach after retirement, traveling in Africa as it grew increasingly independent of European colonialism and speaking out against racism. Throughout the 1960s he was fond of saying that his most recent evangelistic events were “the best ever.” He continued to schedule almost nonstop public meetings and ashrams, sometimes speaking four and five times a day. As he aged, he relied on friends like Mary Webster (see pp. 34–37); yet he remained active almost to the time of his death in India at 89.

Jones often reminded the ashrams that the church’s first creed was the simple statement “Jesus is Lord!” Amid debates and discouragement, it remains a powerful reminder not only for his times, but for our own. CH

By Robert G. Tuttle Jr.

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #136 in 2020]

Robert G. Tuttle Jr. is emeritus professor of world Christianity at Asbury Theological Seminary and the author of In Our Time: The Life and Ministry of E. Stanley Jones.Next articles

“Christ to me had become Life”

Jones’s breakdown and the recovery he found in Christ

E. Stanley JonesThe divine yes to every human need

Jones used ashrams to bring Christ to the Indian context

Tom Albin and Matt HensonFinding Christ at the Round Table

I hear you speak about finding Christ. What do you mean by it?

Mark R. Teasdale“My splendid boys”

The ministry of Mabel Lossing Jones changed Indian education

Martha Gunsalus ChamberlainSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate