The divine yes to every human need

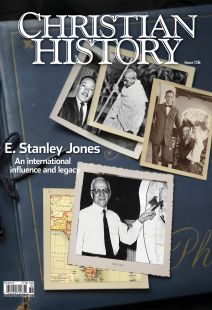

[Stanley Jones with Ashram group—Courtesy of Anne Mathews-Younes]

Deep in the beautiful countryside, spending a tranquil time apart in a place for meditation, prayer, and learning from a guru through teaching and conversation: the ashram experience is common for many Hindu believers, in Jones’s day and in ours. E. Stanley Jones, following several previous missionaries, transformed this indigenous structure with Christian encounter. Rather than placing an earthly guru at the center, his Christian ashram focused on Jesus Christ; because the guru is a “dispeller of darkness,” Jones focused on Jesus, the Light of the World and the living Word of God.

A time away

Long before Jones arrived in India, the practice of leaving normal life routines to gain knowledge on intellectual and spiritual matters existed. In Sanskrit the word ashram is understood to mean “a” (away from) “shram” (hard work).

Indian religious practices adapted to communicate the Christian gospel probably began with Italian Jesuit Roberto de Nobili (1577–1656), who dressed as a sannyāsi (religious beggar) in southern India and engaged Hindus in apologetic dialogue. Brahmabandhab Upadhyay (1861–1907), an Indian Brahmin who converted to Catholicism, is the first-known native Indian to organize a Christian ashram; Christian adaptations exploded in the twentieth century. Poet and convert from Hinduism Narayan Vaman Tilak at Satra founded the first Protestant Christian ashram in 1917. Others emerged in the 1920s, such as the Christukula Ashram in Tirupattur, founded by Ernest Forrester Paton and S. Jesudasan, and the Christa Prema Seva Ashram in Shivajinagar, founded in 1927 by Anglican missionary priest John “Jack” Winslow.

These and other influences helped shape Jones’s ministry. In 1911–1912 he read Indian missionary theologians H. A. Popley and G. E. Phillips. Later he encountered D. M. Devasahayam’s 1922 essay “Indian Characteristics that Should Be Preserved in the Indian Church.” He was soon quoting it in his address to the North India Methodist Annual Conference. And then came Gandhi (see pp. 24–28), who “taught me more of the spirit of Christ than perhaps any man in East or West,” as Jones later wrote. Jones asked him how to “make Christianity naturalized in India, not a foreign thing, identified with a foreign government and a foreign people.”

Beginning in 1923 Jones visited a number of ashrams. At Sabarmati, one of Gandhi’s ashrams, Jones would get up early in the morning to sit and talk with Gandhi, enjoying the person-to-person community granted by the ashram. He also visited the Shantineketan Ashram established by Hindu poet and artist Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) and Anglican priest C. E. Andrews (1871–1940).

The ashram concept reminded Jones of Holiness camp meetings in the United States, with time apart in nature for contemplation and religious teaching; but it was a purely indigenous Indian form for gathering people. Like William Taylor before him, Jones was willing, even eager, to adapt the ideas and structures found in his experience of India to shape his own theory and practice of mission.

The task of the missionary, he thought, is to introduce people to the Jesus of the Scriptures and then trust the Holy Spirit to lead them into the establishment of a Christianity that remained truly Indian and was expressed in Indian cultural categories with a unique and universal power. In his book Along the Indian Road, Jones wrote, “It is the national soul of India expressing itself in religion, the central characteristic of which would be simplicity of life and an intense spiritual quest.”

Group discipline

In 1930 Jones, with the assistance of Indian Christian minister Rev. Yunas Sinha and Ethel Turner (recently retired from the London Missionary Society) established the Sat Tal Christian Ashram. He wrote: “Three nationalities came together in that humble beginning—American, Indian, and English.” Jones was seeking an intentional Christian community with a “group discipline”:

I knew that I was to be a missionary and an evangelist, but saw that many evangelists after a few years of fruitfulness end up quoting themselves and using phrases of sermons that may have once been effective, but now are merely slick, like a coin from constant usage. The danger is that lacking a close-knit fellowship to discipline them, they (the evangelists) become dogmatic, cocksure, and wordy. They are telling others what to do but no one tells them what to do.

The famous gurus of Hinduism each had dedicated ashram locations. Jones bought the Sat Tal Estate near Nainital in 1930 from a Mr. and Mrs. A. C. Evans; Mr. Evans was a retired British engineer, and Jones and his family had previously stayed at Sat Tal in cottages the Evanses made available to missionaries. These 350 acres located in the foothills of the Himalayas provided a place to retreat from the rigors of daily life and a space to experience nature and beauty, as well as a place for prayer, meditation, and renewal.

After several summers of two-month ashrams in Sat Tal, Jones’s desire for a year-round Christian ashram in India was realized at Lucknow. This full-time ashram lasted several years. However, it experienced multiple setbacks and challenges, ending in failure after Jay Holmes Smith, whom Jones had entrusted with leadership, shifted the focus to the political cause of Indian independence from Britain (see pp. 34–37). Jones felt “the disbanding . . . was a calamity at the time.” However, he came to terms with the fact that God could use short-term ashram experiences to help people from all faiths and no faith. What initially seemed a failure became the foundation for the global spread of part-time Christian ashrams around the world.

In 1940 Jones returned to North America to lead the first Christian ashram in Saugatuck, Michigan. The war in Europe forced cancellation of Jones’s travel arrangements from India and required him to sail around South Africa. As the ship made a stop in Trinidad, Jones later said, he felt a prompting of the Holy Spirit to fly to Miami. From Miami he took a train to Chicago where a pastor picked him up and drove to Michigan. As they entered the camp, the bell was ringing to announce the opening service of the first North American Christian ashram. It was God’s ashram and God’s time, he believed.

Initially the Department of Evangelism of the Federal Council of Churches guided the growing North American movement. In 1957 Jones realized that this structure was inhibiting the mission; he decided greater independence and greater local responsibility was needed among the ashrams for the Holy Spirit to guide expansion. With the help of Melvin J. Evans, Thomas Carruth, Joseph Connolly, and Malcolm Gregory, the American (now United) Christian Ashrams was incorporated in the state of Texas. From 1957 to 1967 the movement saw unprecedented growth. When Jones wrote Song of Ascents, in 1968, at the age of 84, Christian ashrams numbered more than 100 across six continents.

Core Principles

Jones and his colleagues emphasized two things in gathering attendees. The first was the importance of equality. The Christian ashram was not only a place to get away from hard work; it was intended to help attendees experience the Kingdom of God in miniature “on earth as it is in heaven.” During the hours or days the community was gathered, they pursued an intentional process to “take down the barriers that separate people from one another,” barriers such as title, race, class, job, and age, and to “take down the barriers that separate people from God”—their ideas of religion, doctrine, theological distinctives, and criticism.

Second, Jones’s ashrams focused on transparency and openness. He welcomed Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Jains, agnostics, and atheists, requiring only that everyone come ready to acknowledge his or her need. Jones said repeatedly, “If you have no needs, do not come to the Christian ashram. If you have a need, a question, a hurt or a desire—come.”

From that day to this day, every Christian ashram gathering begins with a session called “The Open Heart,” an invitation to each person to be transparent and open with one another. Each participant is invited to answer three questions: “Why have I come? What do I want? What do I need from God before this Ashram comes to an end?”

The ashram experience affords ample time to be together for Bible study, meditation, personal prayer, small-group sharing, enjoyment of nature, recreation, shared meals, evangelistic preaching, and a healing service. In the final session, “The Overflowing Heart,” participants share thanks to God for the healing of hurts (body, mind, or spirit) and meeting of needs (emotional, relational, and spiritual). An ashram meeting may be as brief as six hours in a single day or as expansive as the current 14 days of the Sat Tal Summer Ashram sessions.

Word made flesh

Christian movements often rise and fall with the leaders who found them, but the ashram movement has survived Jones by nearly 50 years. It reached its high-water mark in the late 1960s and began to decline during Jones’s later years. However, he was clear that it would never be a large movement. The important thing was that it be a faithful movement: faithful to the person and work of Jesus Christ.

In 2019 more than 2,000 people experienced a Christian ashram in North America and around the world. In addition to traditional ashram events, international leaders are creating new experiences for college students, clusters of local churches, resort settings, and retirement facilities; during the COVID-19 pandemic, some ashrams even went online to offer Christ to all who attended. The movement still desires to be a faithful incarnation of the expansive, generous love of God for all people, men and women from all races and tribes and kindreds and nations—God’s “Divine Yes,” in Jones’s words, to every human need. CH

By Tom Albin and Matt Henson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #136 in 2020]

Tom Albin is director of spiritual formation and congregational life at The Upper Room ministries in Nashville, Tennessee, and executive director of the United Christian Ashrams. Matt Henson is associate director of the United Christian Ashrams and Lead Evangelist/Executive Director for Living the Adventure Ministries.Next articles

Finding Christ at the Round Table

I hear you speak about finding Christ. What do you mean by it?

Mark R. Teasdale“My splendid boys”

The ministry of Mabel Lossing Jones changed Indian education

Martha Gunsalus ChamberlainGod’s adequate answer

Jones describes his hopes and fears about the Round Tables as a method of witnessing.

E. Stanley JonesChristian History Timeline: E. Stanley Jones

The witness of Stanley, Mabel, and Eunice Jones and their colleagues and friends

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate