“My splendid boys”

[Eunice Jones, Mabel Lossing Jones, and ESJ on a boat deck—courtesy of Anne Mathews-Younes]

Soon after the turn of the twentieth century, Mabel Lossing sailed to a life-changing destination: India. She is one of the most accomplished—yet little known—Methodist missionaries, having served 42 years in India, accomplishing miraculous feats through prayer and ingenuity.

Let the women lead

That Lossing arrived in India at all was a direct result of resolute women at the Tremont Street Methodist Episcopal Church in Boston, who had challenged male-dominated control of Methodist funds and formed the Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society (WFMS) in March 1869. They commissioned Lossing as an education missionary in 1904.

Lossing first served in Khandwa in central India, where she became the sole administrator of the orphanage and was also one of only two teachers. Among her tasks was to search the streets for abandoned children. At the same time, she honed her skills as fund-raiser and innovator, and also completed her master’s degree from Upper Iowa University in 1906, while studying and practicing Hindi four hours a day. She eventually learned Urdu, Sanskrit, and German, and studied classical languages including Greek and Latin, bemoaning the insufficient number of hours in the day.

As news of Lossing’s extraordinary administrative ability and gifted teaching continued to spread, she was sent to Jabalpur to start a teacher training school, now called Havabagh, meaning “fresh air,” and then to Lucknow to the Lal Bagh Teacher Training School.

Meanwhile E. Stanley Jones arrived in India in 1907, appointed by the Methodist General Board of Missions to serve the English-speaking Lal Bagh Methodist Church in Lucknow. Lossing played the organ at the church for about a year without ever meeting the young preacher, until one day he approached her in the aisle. One biographer wrote that Stanley Jones “wasn’t quite sure how to proceed with romance.”

After marriage, Mabel and Stanley at first worked together in Sitapur with three schools in physical and academic disrepair. But Stanley was no educator. As he moved fully into his call to evangelism, Mabel Jones strode confidently into her own call. The schools served 200 boys, many of them orphans in a boarding school.

No one in India had heard of a female “headmaster” for a boys’ boarding school, or of women teaching boys, or of a Caucasian serving on the municipal council of a city. But to raving accolades, Jones served 20 years on the Sitapur Municipal Council—the only female, the only non-Indian, the only American, and certainly the only Christian to have served the evenly divided Muslim/Hindu council.

“I’ll take it to my grave”

While Jones knew she could not change centuries-old protocol quickly, she determined to find ways. When the male teacher of the kindergarten boys became ill, she told him to have his wife teach the class. Year after year she gradually brought in more women teachers until only women taught the children. After an initial uproar, all saw that the boys had learned more than those in any other school, and Jones had instilled respect for women in male students.

In 1914 Jones gave birth to Eunice, separated by oceans from family and even from her husband engaged in God’s “other” work. Eunice’s primary spoken languages were Hindustani and English. Bhulan the Muslim cook took seriously his role to teach Eunice to talk. Carrying her about the house, he pointed to various objects, stating their names in Urdu or Hindustani, enjoying her quick childish response and ready wit.

In addition to teaching, Jones had dreamed of becoming a journalist. Already published in Harpers and The Atlantic Monthly, she continued to write, but under a pen name so that she would not compete with her husband’s writing. Years later when Eunice saw a check arrive from a major American magazine, she begged her mother to reveal her pen name, but her mother replied, “I’ll take that secret to my grave.” So she did. Jones also wrote under her own name for the Woman’s Missionary Friend and the Junior Missionary Friend to connect young Methodists in the States with missionary life on foreign soil.

Mabel Jones wrote each donor who sponsored a child at her school, no matter how small the gift. She solicited funds with stories rather than asking outright and habitually hand-wrote more than 20 letters a day, raising enough to keep 1,000 boys in school per year. She also sent regular updates to the director of missionary outreach at home, Ralph Diffendorfer, and carried on a lively correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi on education and disciplinary matters.

Jones’s dream of a library for her schoolboys led her to request book donations from US Sunday school children. When the boys’ clothes became torn or tattered, Jones added daily “patching bees” to the schedule and taught the boys to make and mend their clothing. And when Eunice had one too many close calls with snakes at their home, Jones tapped into her Canadian grandfather’s practical ability as a builder and upgraded the property by building a long-needed septic system and a Persian water wheel. Next she built another mission house, nearer the school. But, even in the new house, snakes occasionally found them.

Like her husband, Jones knew she must connect with the community in meaningful and respectful ways if she was to reach them with the gospel. She joined the Red Cross Society, the Public Health Committee, and the Baby Week Committee; visited women in the jail; and was appointed to the District Board, which oversaw roads, schools, hospitals, dispensaries, and other public facilities that served more than a million people.

One day as Jones lunched at the district magistrate’s home, a Muslim official thanked her for a book she had given him about the life of Christ. He said, “I have almost finished the book, and I must say that I am sorry and disappointed that I can find nothing in it of which I disapprove.”

Jones learned that literature and music opened the door to conversation about Christ. Well-versed in Urdu and Hindi, she read the Bhagavad-Gita and knew the Qur’an quite well. “She knew full well,” wrote her son-in-law, “that one could not hope to witness effectively to what she knew was sacred for Christians without a deep comprehension of what Hindus regard as sacred. Too often this has escaped the missionary.”

The floods came up

Just after World War I ended, a cataclysmic event hit their world. Mabel Jones had become the on-call “doctor” for an extended community. One day she was called to a schoolboy writhing in abdominal pain and vomiting. Within hours he was dead from cholera. Within six weeks the district lost 10,000. In desperation Jones began sending telegrams to parents of well children. But one child after another died upon reaching home, already exposed. She wrote:

Each day brought . . . more deaths until I felt I could bear no more. My splendid boys, bright, clean, healthy, happy, promising little lads who had been with me until they seemed like my own sons, [were] snatched away while we stood helpless.

They lost more than 40 children. Then the great 1918–1919 influenza epidemic ravaged the globe. Of 22 million deaths worldwide, more than half were in India.

In 1923 Bishop Jaswant Chitambar, Stanley Jones, and Bishop Waskom Pickett met in Arrah for a meeting and prayed with concerned people for much needed rain. About 4:30 the next morning as they slept on the mission house roof, Pickett awoke to the sound of water. It had not rained, but a mystery river not 40 feet from the mission house was rising seven inches per hour.

At home Mabel Jones was experiencing her own trouble; a little creek a quarter of a mile from the bungalow filled the schoolhouse. Spared any loss of life or serious damage, the children and adults worked together to clean up. Before long, however, the waters again overflowed. Miraculously no lives were lost. But Jones’s new mission house had doorsills several inches high to help block the entrance of small animals, which provided a lovely pool for fish. Unadulterated delight filled eight-year-old Eunice.

The year’s supply of rice was totally submerged for days in the brick storeroom. As the grain swelled in the steamy moist quarters, it also cooked, pushing the walls outward—undoubtedly the world’s largest rice cooker. “Oh God, what shall I do?,” Jones prayed earnestly. As survivors crawled back to their villages, the news spread. “Tell the people I have food for them!” she announced. Long lines quickly formed.

Even merchants respected Jones in her endeavors, though they tried tempting her. More than once she discovered a 100 rupee note in the bottom of the basket with fruit she had ordered. She returned the basket with a note and the money that had been “mistakenly” placed in her basket, thanking them for the good fruit her boys enjoyed. She divided chores among boarding school students who weekly rotated jobs such as gardening and gathering food for the cook; the students ate stewed lentils with oatmeal in the morning and curried rice with onions for dinner.

“Dear Miss Jones”

In the 1920s donations for missions dwindled, and then the 1929 stock market crash and the Great Depression hit like a tsunami, wiping out even the meager donations that had kept the mission school afloat. Jones had no choice but to continue translating the boys’ simple thank-you letters from Hindustani into English and to answer hundreds of others herself.

Stanley’s Christian ashram (see pp. 12–15) was located about 12 miles from his family when Mabel and Eunice lived in Nainital in the mountains during the two summer months, allowing them to spend treasured time together. Stanley taught Eunice to play tennis and badminton—not considered women’s games in that era. The pair also took long hikes together into the fields and villages adjacent to the compound. “We often walked five miles, passing through villages where the people always welcomed us. Indians are very hospitable,” Eunice reminisced.

Eunice attended college in the United States and then rejoined her parents, helping her mother at the mission and her father as secretary on his evangelistic tours and typist of his books. In 1939 Stanley was scheduled to preach and teach for a week in Poona; he and Eunice stayed with a missionary couple. The wife gushed that a young man who was coming was the one for Eunice. Eunice refused to entertain any interest, but young missionary Jim Mathews said he was “smitten when Eunice walked into the room and into my life.”

Mathews attended Jones’s lectures, but he and Eunice carved out time to bicycle and even to tour the countryside in a car. Back in Bombay, he began a letter: “Dear Miss Jones.” He later learned that her father had to assist in deciphering his scrawl. The two were married on June 1, 1940, in the teak-paneled chapel of Wellesley School in the Himalayas.

Mabel Jones returned to the United States to stay in 1946, but continued to work even after 42 years in India. She waited for her husband in their supposed retirement home in Orlando, Florida, but he continued his ministry and could not bring himself to retire. So skillful was she at writing letters that at age 90 she was still raising money to support her boys in India. In fact her letters generated such phenomenal revenue that Diffendorfer asked her to prepare a model for other missionaries.

On learning that her eyesight was failing, Jones hurriedly read all of Shakespeare’s plays within a two-week period so that she could reflect on them when it failed completely. Upper Iowa University, her alma mater, honored her with a Doctor of Humanities degree.

Stanley died in 1973, and that year 95-year-old Mabel fell and broke a hip. She would live her remaining days near Eunice and Jim. Mabel Lossing Jones died peacefully on Friday, June 23, 1978, at the age of 100 years, after a century of God-anointed global ministry.

The Mabel Jones Boys School continues to educate and shape young lives to this day. When Mabel Lossing was sent to “rescue” the school, little did anyone expect that by her sheer work, will, and faith she would change elementary education for boys throughout north India. Through her courageous innovations, not only are women teachers acceptable for boys, but a new respect for women pervades the system and the lives of now-grown men who benefited from her tutelage. Even today about a thousand boys continue to be educated each year through Mabel Jones’s scholarships. CH

By Martha Gunsalus Chamberlain

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #136 in 2020]

Martha Gunsalus Chamberlain is the author of A Love Affair with India: The Story of the Wife and Daughter of E. Stanley Jones, from which this article is adapted with permission.Next articles

God’s adequate answer

Jones describes his hopes and fears about the Round Tables as a method of witnessing.

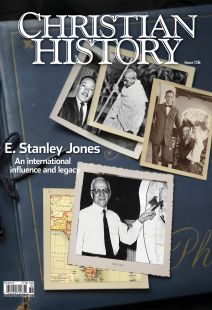

E. Stanley JonesChristian History Timeline: E. Stanley Jones

The witness of Stanley, Mabel, and Eunice Jones and their colleagues and friends

the editorsFollowing Christ on the international road

Jones traveled constantly as a preacher and spiritual leader

Douglas W. RuffleSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate