Following Christ on the international road

[Dr. E. Stanley Jones, 1957. courtesy of GCAH of The United Methodist Church, Madison, New Jersey]

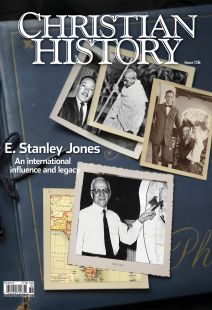

One Methodist bishop, referring to E. Stanley Jones’s tireless pace, called him “the greatest Christian missionary since Saint Paul.” Translations of Jones’s books fueled his recognition around the globe, and he eventually spoke on all six inhabited continents. The fame of his books often preceded him—they were, as his official biography at the United Christian Ashrams notes, “read around jungle fires, studied by armies and governments, quoted in parliaments, and banned and burned by Communists.”

Preaching two a day

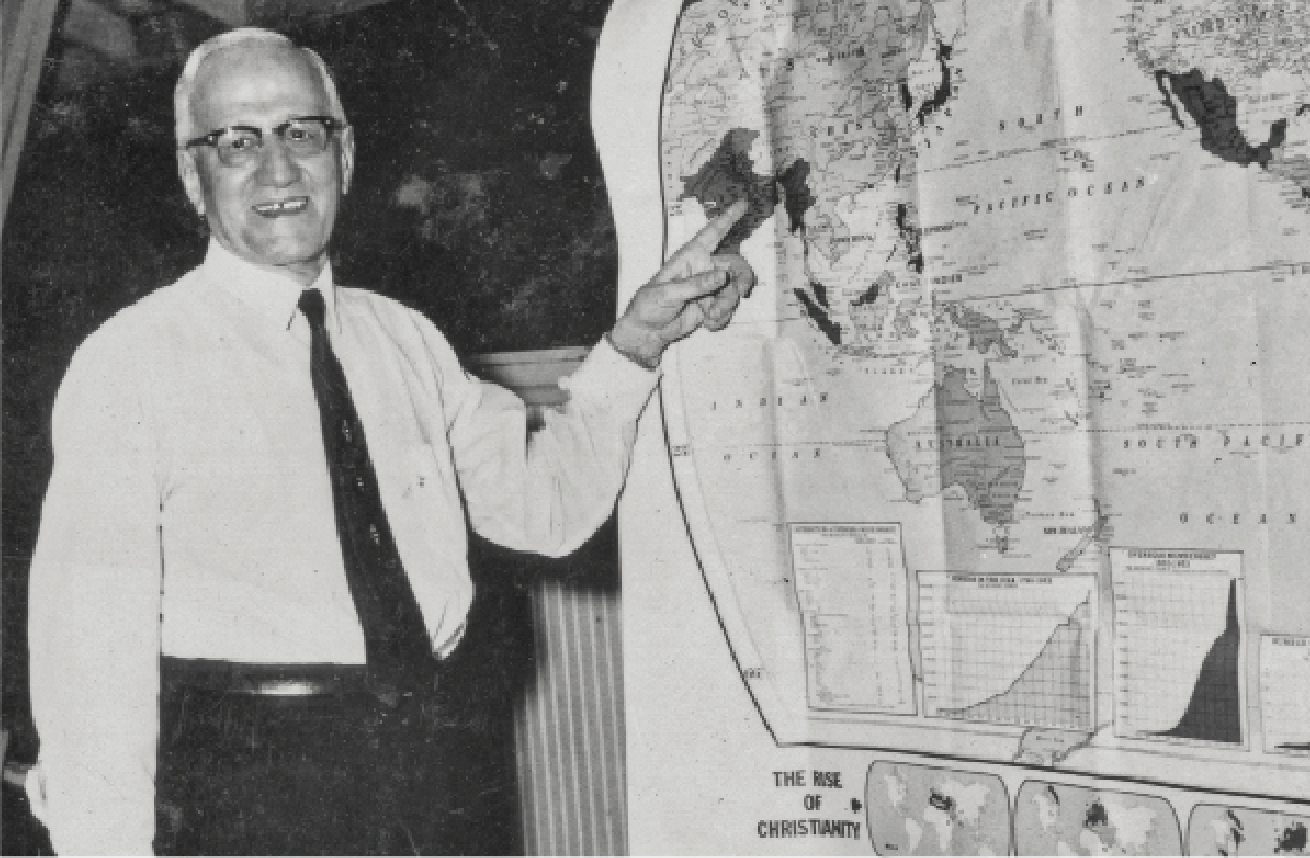

Jones evangelized frequently in China, Japan, and Scandinavia; he also traveled throughout the United States, especially as he guided the US ashram movement into being (see pp. 12–15), and is known to have spoken in almost 500 different churches. Even after his official retirement as a missionary in 1954, he continued to speak worldwide, especially in Asia and Latin America, traveling overseas six months out of every year. His obituary in the New York Times claimed that in 1963, Jones had 736 preaching engagements—approximately two per day!

In his earlier years, until the growing popularity of air travel in the late 1940s, Jones traveled by ship or train. Getting from one place to another took months. This helped produce Christ’s Alternative to Communism, written in 1935 after he returned to India by ship and by train from the United States. His circuitous route took him to Europe, then Russia, and then on to India.

Russia intrigued him. At the time, during the Great Depression, the Soviet Union seemed to be working well, with its factories humming and workers paid. He was impressed by its functional system, but alarmed that all this was being done in the context of an atheistic doctrine. Jones objected to communism because of its lack of liberty and its materialistic atheism. But he also respected its attempt to found a society on cooperation. He was harshly criticized because he took communism seriously and described it in objective terms.

From Argentina with love

A Latin American pastor, Carlos Gattinoni, who would become the first bishop (1969–1977) of the Evangelical Methodist Church of Argentina, translated Christ’s Alternative to Communism into Spanish. The translation led to invitations for Jones to visit Latin America. Gattinoni shared the story of one visit in the late 1950s or early 1960s with an interviewer—a story no doubt repeated, though differing in details, in the many places Jones preached:

[Jones] had been scheduled to lead a weeklong Ashram in Uruguay. When his plane arrived in Montevideo, he found out that there had been a miscommunication along the way and the Uruguayans were not prepared for him. He had come a long way and, of course, back then, it took months to exchange letters.

It was a Saturday in January, and he called me from Uruguay to see if we might be able to arrange something in Buenos Aires on the spur of the moment. I told him we would do what we could, and yes, we could arrange for him to preach in the evening at First Church in the city center. I said that many people were on vacation and that it was hot and we would not have time to advertise, but we would try.

Jones boarded a ferry to cross the 70-mile-wide Rio de la Plata, separating Uruguay from Argentina. He arrived on Sunday morning. Gattinoni continued:

I called several of our pastors and friends from other denominations. We announced in church on Sunday morning that E. Stanley Jones would be preaching at First Church beginning that evening. I urged them to spread the news and to pray for the event and to invite friends and to come.

Quite frankly, I was worried that we would get a very poor turnout. It must have been the prayers. The church was packed that night—standing room only. . . . It remained packed every night for a week. There was something about his preaching style—even with my translation—that had people coming forward to enter into a relationship with Jesus Christ.

Other Argentinian Christians echoed Gattinoni’s testimony. Pastor Hugo Urcola of the Evangelical Methodist Church of Argentina recounted a visit by Jones to Buenos Aires where he led an ashram. “I found myself getting on my knees to receive prayer and anointing from Jones during the Ashram,” recalled Urcola. “To my left, kneeling with me, was Emilio Castro, who one day would become General Secretary of the World Council of Churches. To my right knelt José Miguez Bonino, who would become one of the most influential Christian authors from Latin America.”

Jones’s aims in his travels were sometimes political as well as spiritual; he negotiated out of his conviction that “the only kind of world worth having is a world patterned after the mind and spirit of Jesus.” Some in Africa called him “the Reconciler,” as he famously attempted to negotiate peace between warring groups in India, Burma, Korea, and the Belgian Congo.

Though he ultimately failed to avert war between the United States and Japan, his efforts were remembered; the first time he arrived in Japan after World War II, banners greeted him reading “Welcome to the Apostle of Peace.” In 1962 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for his reconciliation work.

Trusting change to Jesus

Jones rooted his openness in “an untrammeled Christ.” At home in India and on his travels, he put himself in the challenging position of speaking to the truth he knew in Christ in dialogue with learned Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, and skeptics, who in turn spoke to the truth they knew in their religions and their experiences in an atmosphere of civility, mutual respect, and humility.

Jones believed this approach was grounded in Scripture, quoting Paul: “We refuse to practice cunning or to falsify God’s word; but by the open statement of the truth we commend ourselves to the conscience of everyone in the sight of God” (2 Cor. 4:2). He wrote in The Christ of the Indian Road, “Jesus appeals to the soul as light appeals to the eye, as truth fits the conscience, as beauty speaks to the aesthetic nature.”

Jones carried this mindset with him as he spoke around the world, desiring the people of each city or town to discover the Christ who walked with them, was recognizable among them, and fully understood their context. He trusted the power and truth of the gospel of Christ and became vulnerable to others.

The questions he asked still echo today: Do we have answers to life’s questions? Or are we merely living out traditions of our belief systems that now are out of sync with reality? Can we go deeper with one another to unveil the meaning of life? Can we let, as Jones so eloquently stated, “deep . . . speak to deep”? CH

By Douglas W. Ruffle

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #136 in 2020]

Douglas W. Ruffle is director of community engagement and church planting resources at Discipleship Ministries. He is the author of A Missionary Mindset: What Church Leaders Need to Know to Reach Their Community—Lessons from E. Stanley Jones, from which this article is adapted.Next articles

Working from the victory

Colleagues, friends, and influences on the life and ministry of Jones

Jennifer BoardmanMy grandfather, evangelist and prophet

E. Stanley Jones’s granddaughter shares her reflections on his life and legacy

Anne Mathews-YounesBrother Stanley’s legacy: A reflection

He preached extensively in almost every country of the world, which gave him a firsthand view that few people on the planet had

Stephen RankinSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate