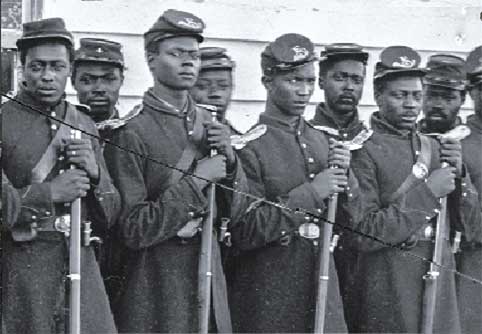

March to freedom

African American troops, 4th colored infantry.

African American Baptists have transformed the moral and social landscape of the United States. When we honor Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968), we also honor black Baptist spaces and leaders that formed him. When we observe Black History Month, we pay homage to its founder, Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950), from the Shiloh Baptist Church in Washington, DC. First-ever female bank president and legend of the black freedom struggle Maggie Lena Walker (1864–1934) was a long-time member of the First African Baptist Church of Richmond, Virginia.

However this transformation came through an enduring tension: Baptists of African descent pushing back against the heavy hand of racism in their march to freedom as they built their institutions and uplifted their race.

From Fervor to Freedom, 1740–1845

The Great Awakening of the eighteenth century introduced the power of the evangelical message of salvation. That compelling message led many churches to grow—chiefly Methodist and Baptist churches. Many new members were enslaved people of the southern states. The traditional religions of their African ancestors provided a foundation consistent with Christianity. But it soon became apparent that in practice, Christian slaveholders behaved inconsistently with the spirit of a religion focused on freedom.

White Christians debated converting enslaved Africans. Some said slaves would be better laborers upon conversion. Others discouraged conversion, catechesis, and baptism, feeling it would prompt Africans to see themselves as equals of those persons who held them as chattel. These debates did not stop African converts from embracing and expressing their faith. The congregational polity of the Baptist Church and its emphasis on experience gave African American Baptists a particular avenue to practice and preach the Gospel.

By the end of the eighteenth century, white Baptists licensed enslaved men across the South as preachers. In Georgia the Buckhead Creek Church licensed and ordained George Liele (1750–1820) “to perform missionary labors among slaves on other plantations in the surrounding area.” He also organized the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia, with Andrew Bryan, and later became a missionary to Jamaica.

In Mississippi Joseph Willis—a free African—was licensed to preach the Gospel in 1798. He became the first moderator of the Louisiana Baptist Association in 1818, after serving as a pastor and church organizer. Another preacher enslaved from birth, “Uncle Jack” (c. 1746–1843), earned his freedom and impressed white church members during his Baptist ministry in the 1790s, mostly in Virginia. He was so captivating that a white Presbyterian minister, William White, wrote a biography about him, The African Preacher (1849).

Peter Randolph, born enslaved around 1825, gained his freedom in the 1840s and became a Baptist preacher. In Sketches of Slave Life (1855), he wrote:

Among the slaves, there is a great amount of talent . . . which, if cultivated, would be of great benefit to the world of mankind. If these large minds are kept sealed up, so that they cannot answer the end for which they were made, somebody must answer for it on the great day of account.

As the nation embraced its new-found independence, African Baptists began to build independent congregations, leaving many white Baptist churches or other black congregations to do so—from Petersburg to Williamsburg to Charles City to Norfolk. Baptist polity gave them permission to receive their direction from God alone. To be sure the laws of the commonwealth would have some say in how that happened.

Often black congregations blossomed with influence—or interference—from white sister churches. In Richmond, Virginia, black congregants outnumbered white ones briefly at the the biracial First Baptist Church; that church licensed Lott Carey, who became the first American Baptist missionary to Africa in 1821. But the black members of First Church formed their own congregation in 1841. The gospel of freedom that produced these Baptist pioneers and institutions still betrayed problems in the larger culture. Black Baptists were still black, and racism was still prevalent.

Buy Christian History #126 Baptists in America.

Subscribe to Christian History.

Up From Freedom, 1845–1895

As an oppressed people, African Americans sought to challenge longstanding institutions of white supremacy; as part of the larger Baptist family, their energy and influence led to conversations about Baptist commitment to real freedom. Baptists debated slavery in the years following the unifying Triennial Convention of 1814. They had merged for the sake of missions and education, but the cultural divide between the states was growing. Black Baptist associations and conventions began forming across the country with a focus on abolishing slavery and its influence. When their efforts were frustrated, they pushed for an independent national denomination.

They watched as Baptists in the South split from the Triennial Convention in 1845 and continued to watch the larger society’s simmering conflict result in the Civil War, a failed Reconstruction, and the rise of Jim Crow laws. And they became more and more determined to develop a national church; though northern missionary societies supported them on the mission field and in education, black Baptists believed they would best determine their course in a church of their own.

Fifty years after white Baptists split in 1845, the merger of numerous black conventions led in 1895 to the National Baptist Convention USA, Incorporated (NBC). Elias Camp Morris (1855–1922), its first president as well as a political leader in Arkansas, wrote in his 1901 memoir:

The writer firmly believes in the possibilities of the race and has firmly advocated that the nearly two millions of colored Christians which God has added to the Baptist churches as a mass, are an heritage, and that it is the imperative duty of Negro Baptist leaders to develop this mighty force for the glory of God and the further redemption of the race.

If It Wasn’t For the Women, 1895–1965

Black Baptist women were a major force in the growth of these churches, associations, and conventions—establishing strong societies that supported mission work in the fields of education and evangelism. Sought-after evangelist and teacher Virginia Broughton (1856–1934) shaped NBC mission work, wrote for denominational newspapers and magazines, called attention to efforts of the women’s convention, and mentored the next generation of women. In Twenty Years’ Experience of a Missionary (1910) she wrote: “The Negro woman is doing a noble part to forward every righteous movement that makes for the peace and uplift of humanity and the glory of God.”

One of Broughton’s protégés, Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879–1961), would later wield influence in the denomination and the women’s auxiliary (see “Preachers, organizers, trailblazers,” pp. 36–40). Burroughs rose up the ranks of Baptist and black American life to become an officer in the Women’s Convention Auxiliary. Her leadership ability and organizational prowess gave the women a singular focus as forces for good within the denomination and society. They embraced a social agenda that included the founding of the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909, embodying its founder’s push for excellence.

Black Baptists faced numerous challenges in their march to freedom; these issues would remain through the civil rights era (see “That’s where I used to go to church,” pp. 32–35) and beyond in the lives of leaders like Samuel DeWitt Proctor (1921–1997), president of Virginia Union University; Howard Thurman (1899–1981), dean at Howard University and Boston University; and Prathia Hall (1940–2002), activist, preacher, and theologian.

When King famously reminded his audience in 1963 from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, “We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream,” he spoke as an American asking his country to make good on its promises of freedom. He also spoke as a Christian and a Baptist, reminding his audience of freedom’s source. CH

By Adam L. Bond

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #126 in 2018]

Adam L. Bond is associate professor of church history at the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology, Virginia Union University and the author of several books and articles on the Baptist experience. He is an ordained minister in the American Baptist Churches USA and senior minister of the Providence Baptist Church in Ashland, Virginia.Next articles

"For the public worship of almighty God and also for commencement"

Baptists founded schools early and often for many purposes

Amy WhitfieldChristian History Timeline: Baptists, 1600–2000

How a small group of English dissenters ended up transforming American religion

Association of Religion Data Archives, the Baptist History and Heritage Society, and other sourcesA trumpet call for China: Lottie Moon

Lottie Moon remains the most famous Southern Baptist missionary of all time.

Melody MaxwellSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate