A land called holy

[Untergriesbach (Lower Bavaria). Epitaph for Georg Fuchs, parish priest in Gottsdorf, died in 1839: Allegorical relief on supersessionism: God dismisses Israel and closes a new covenant with Christianity—Wolfgang Sauber [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE] / Wikimedia]

Since before Christianity emerged as distinct from Judaism, the area known as the Land of Israel or Palestine or the Holy Land has held special significance. The desire to exercise political sovereignty over Jerusalem has animated conflicts among Christians, Jews, and Muslims throughout history.

The modern State of Israel, founded in 1948, inherited this historical significance. While some Jews had migrated to this area across the centuries, the state’s founding resulted most directly from Jewish immigration to the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth century. Spearheaded by German Jewish activist Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), the Zionist movement encouraged immigration as it sought the establishment of a Jewish state.

In 1917 the Balfour Declaration—a letter by British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour to Walter Rothschild, a prominent Jewish British nobleman—expressed support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” provided “that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” After the Allies defeated the Ottomans in World War I, the British took sole occupation in 1923 under what was called the Mandate for Palestine. The rise of Nazism and the ravages of the Holocaust led to a steady stream of Jews hoping to immigrate.

In February 1947 the United Nations proposed a plan to partition the area between Jewish and Palestinian Arab residents, but on the day before the mandate ended in May 1948, Jewish leaders declared independence. War followed, leaving Israel in control of about three-quarters of the formerly mandated area. In 1967 Israel captured and began occupying further territory.

Was this prophecy?

That these events happened is (mostly) uncontroversial. Because this nation-state of the Jewish people carries theological significance for many Christians as well, these geopolitical events sparked spiritual imagination. Some Christians viewed the founding of the State of Israel as prophetically significant, a doctrinal commitment that has translated into a generally favorable evaluation of Israel’s conduct. Other Christians considered themselves prophetically agnostic—holding no belief about the State of Israel’s prophetic role, but supporting it as a place for Jews to escape religious and political persecution.

A third approach developed mainly after Israel expanded in 1967, occupying areas outside the territory established in 1948. Some Christians began to consider themselves critically prophetic, convinced that Palestinian suffering under Israeli sovereignty or military rule demanded prophetic witness against state violence. Instead of viewing the State of Israel as “the apple of God’s eye,” they believed that Israel was to be judged alongside other states and according to the same standards.

For centuries most Christians had held to the notion that the “New Covenant” established by Jesus had significantly diminished or eliminated any Jewish claim of being God’s “chosen” people. Any positive promises God had made to the Israelites had been transferred to Christians, including covenants of land. This is known as “replacement theology” or “supersessionism.”

Among Western Christians this view was challenged in 1965, when the Second Vatican Council issued Nostra Aetate. It repudiated a previous Christian teaching, the “teaching of contempt,” that Jews were always and everywhere responsible for the death of Jesus. This led to a new era of Jewish-Christian theological dialogue, but political questions regarding Israel remained unaddressed.

Israel’s dramatic territorial expansion in 1967 changed things. On one side many Catholic and mainline Protestant churches saw Israel’s annexation of an expanded East Jerusalem and military occupation of greater territory as violations of the Fourth Geneva Convention. On the other side many evangelicals interpreted these events as stages in the fulfillment of biblical prophecy, including the miraculous rebirth of Jewish sovereignty over their undivided capital city.

From then on support for the State of Israel became a central plank in evangelical theology—from Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority in the late 1970s to John Hagee’s Christians United for Israel in the early 2000s. They interpreted the State of Israel as a prophetic “sign of the times” and viewed Israel as an ally in the Cold War. But the underpinnings of this theopolitical interpretation had actually been formed centuries before.

“The pope and the Turk”

The system of biblical interpretation known as premillennial dispensationalism (see CH #128) is usually considered the most recent historical source for evangelical attitudes toward the State of Israel. Created by John Nelson Darby (1800–1882) in the late 1800s and popularized by Cyrus Scofield (who developed the Scofield Reference Bible, first published in 1909), this system emphasizes a distinction between Jews and gentiles as two separate peoples of God.

This way of reading the Bible grew out of long-established English Protestant traditions of prophecy interpretation. In the Reformation era, Protestant Christians felt themselves to be facing two existential threats: the Roman Catholic Church and the Ottoman Empire. Both Martin Luther (1483–1546) and John Calvin (1509–1564) referred to these threats, respectively, as “the Pope and the Turk,” which together they identified as the Antichrist.

The crises of the sixteenth century sparked renewed interest in apocalyptic interpretation of the Bible. Searching the Scriptures for aid in these struggles, English Protestants as early as 1585 began identifying Jews as allies. These were not actual Jewish communities in England; Edward I had officially banished Jews three centuries before. Having little to no experience with living Jews, the English Protestants viewed Jews as literary characters for their purposes in God’s narrative.

By the 1630s English Protestant theologians had developed precise apocalyptic plans in which Jews, upon their return to Palestine, would form an army and defeat the Ottomans. This would, in turn, aid the Protestant struggle against Rome. These anti-Islamic and anti-Catholic ideas were deeply woven into the Puritan struggle as Puritans separated from the Church of England and (temporarily) eliminated the British monarchy in favor of a Puritan commonwealth.

In 1649 Johanna and Ebenezer Cartwright, English subjects living among Jewish communities in the Netherlands, joined their theological ideas to a political proposal. Their petition, written in part to Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell, suggested that aiding a Jewish return to the “Land promised to their fore-Fathers” would appease God’s wrath manifested in the English civil war. This political effort, undertaken to promote Jewish sovereignty over the Holy Land for specifically Christian purposes, is the first documented example of Christian Zionism.

Old Testament, new world

Puritan settlers such as John Winthrop (1588–1649) and Increase Mather (1639–1723) carried these ideas to the New World. Through them the English Protestant tradition of Jewish-centric prophecy interpretation was woven into America’s founding story.

Often Puritan leaders imagined English settlers through the biblical image of the Israelites in the wilderness. Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, declared it was “as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” With the stroke of a pen, the New World became “the Promised Land” and the indigenous peoples the “Canaanites,” who would eventually yield to the English settlers who saw themselves as conquering Israelites.

Subsequent generations of English settlers turned their attention toward the theological significance of America itself, mapping elements of the Hebrew Bible onto life in New England. In addition to promoting the study of Hebrew at newly established universities like Harvard and Princeton, Puritans often named their children with Hebrew names of Old Testament characters and named places with Hebrew names drawn from the same narratives.

Increase Mather’s son, Cotton (1663-1728), and Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) displayed acute concern for the place of England and America in God’s apocalyptic timeline. Ideas about how and when Jews would be restored to the Promised Land were a common matter of public debate. Some, like the Mathers’ friend Samuel Sewall, wondered if America might even be the site of God’s New Jerusalem. These speculations (which later teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints would explicitly reflect) helped form the idea of America itself.

Premillennial dispensationalism took hold in the United States following the Civil War. Studied at prophecy conferences throughout the nation, the system helped make sense of recent national trauma. For Chicago businessman William E. Blackstone (1841–1935), these theological ideas formed the basis for political action similar to that of the Cartwrights of the 1640s. In 1891 he presented a petition, signed by prominent politicians, publishers, and business leaders, to President Benjamin Harrison.

The “Blackstone Memorial” argued that the suffering of Russian Jews should be alleviated by giving “Palestine back to them again.” This was logical because “according to God’s distribution of nations it is their home, an inalienable possession from which they were expelled by force.” US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis and other prominent Jews—who endorsed the Jewish expression of Zionism—supported Blackstone’s effort.

Today, in a post-Holocaust world, the debate rages on. The modern nation-state of Israel cannot be separated from either the long history of Jewish-Christian relations or specific Judeo-centric prophecy interpretations viewing “the Pope and the Turk” as the antagonists whom such a state must overcome. The land may be called holy, but its history is also fraught. C H

By Robert O. Smith

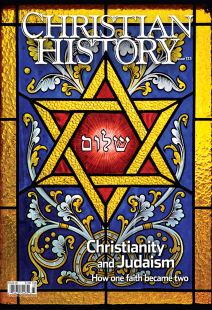

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #133 in 2020]

Robert O. Smith is director of Briarwood Leadership Center, Argyle, TX; he previously directed the University of Notre Dame’s Jerusalem Global Gateway. He has written or edited More Desired than Our Owne Salvation: The Roots of Christian Zionism; Christians and a Land Called Holy; and Comprehending Christian Zionism.Next articles

Nozrim and Meshichyim

Messianic Judaism combines Jewish and Christian influences, but not without controversy

Yaakov ArielExperiencing Messianic Judaism

Paul Phelps“Our Jewish life”

Jewish thinkers, writers, leaders, and artists with lasting impacts

Jennifer A. BoardmanSorrow and blessing

Two theologians seek to illuminate the difficult history in this issue

Ellen T. Charry and Holly Taylor CoolmanSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate