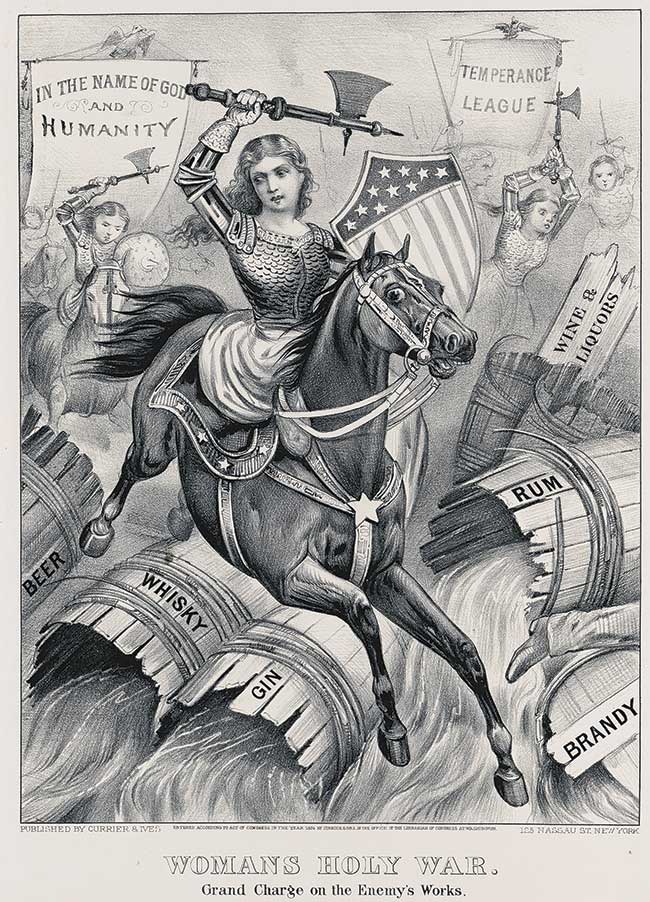

Christ versus the rum shops

[Woman’s holy war. Grand charge on the enemy’s works. Lithograph, c.1874—Currier and Ives / Library of Congress]

It was October 1874, somewhere in Chicago, when the unassuming, slender, bespectacled Frances Willard (1839–1898) began her call for reform. History was being made that day. With her trademark combination of gentleness and power, humor and quiet reserve, she took the podium. “We are taught to pray: ‘Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done,” she told her listeners:

Where? “On earth.”. . . We as a people believe what this good book says when it plainly again and again declares that Christ is again going to rule on earth. How is he going to rule until we get all the rum shops out of the way?

“Grape juice, grisley sermons”

Willard delivered this speech, “Everybody’s War,” for the first time that day; she would repeat it many times over the next decades. In November 1874 she attended the founding convention of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), and by 1879 she became the organization’s president. Years later historians would stereotype Willard, the WCTU, and indeed the entire temperance movement as Bible-quoting fundamentalists; in 1920 Charles Beard (1874–1948), a founder of the New School of Social Research, described prohibition supporters as full of

Philistinism, Harsh restraint, Beauty-hating, Stout-faced fanaticism, Supreme hypocrisy, Canting, Demonology, Enmity to True art, Intellectual Tyranny, Grape juice, Grisley [sic] sermons, Religious persecution, Sullenness, Ill-Temper, Stinginess, Bigotry, Conceit, Bombast.

But, in the 1800s, temperance, like women’s suffrage and abolitionism, stood in the foreground of the Progressive reform agenda. And many of these activists grounded their work in the Bible.

Organized reformers thronged the nineteenth-century United States, many organizations arising in just over two decades: American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1810), American Education Society (1815), American Bible Society (1816; see pp. 29–31), American Sunday School Union (1824), American Tract Society (1825), American Temperance Society (1826), American Home Missionary Society (1826), and American Anti-Slavery Society (1833). Numerous denominational societies were founded around the same time.

“Not a letter but a life”

Temperance activists believed the Bible does not affirm intoxicating drinks, and abolitionists preached that Scripture teaches freedom for those enslaved. In both cases they fought uphill interpretive battles, as Scripture does not unequivocally condemn either. Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy regulate slavery; Jesus’s parables speak of slaves; and Paul’s letters assume Christian households include slaves. Proslavery advocates argued repeatedly from these texts (see pp. 16–18).

Similarly, the Bible pictures the coming kingdom as “a feast . . . of well-aged wines strained clear” (Isaiah 25:6). Jesus changed water into wine at a wedding (John 2:1–12) and commanded his followers to eat bread and drink wine. Many Christians believed this gave biblical support to moderate alcohol consumption and to using wine in Holy Communion.

Specific passages do support the other side, of course. Foes of drinking could point to Proverbs 23:31–32 and Ephesians 5:18; foes of slavery to Galatians 3:28 and to Exodus 21:5–6. But abolitionists often spoke in more general terms: they pointed out that slavery in the Old Testament is not race-based and not generally permanent, and they appealed to the overall scriptural depiction of God’s mercy and love. Abolitionist Gerritt Smith (1797–1874), also a temperance campaigner, argued in his Three Discourses on the Religion of Reason (1859) that “the religion taught by Jesus is not a letter but a life.”

Temperance activists also believed an overall commitment to God’s mercy compelled them to speak up against a destructive addiction; Charles Fowler (1837–1908), president of Northwestern (and Frances Willard’s ex-fiancé) wrote in his Wines of the Bible (1878) that if Jesus was on the side of wine drinking, he was on the side of “wife-beating and child-beating” and “seven-eighths of all the crimes committed in the civilized world.”

But they also developed a method of biblical interpretation known as the “two-wine theory.” Congregationalist professor Moses Stuart (1780–1852) popularized this argument in Scriptural View of the Wine Question (1849); he argued that both fermented and unfermented wine appear in the biblical text; any praise of wine must refer to the unfermented version.

A “total abstinence Bible”

The argument soon predominated among American temperance advocates and spread to Britain, where Anglican orator Frederic Lees (1815–1897) and Baptist minister Dawson Burns (1828–1909) produced the Temperance Bible Commentary (1868); their careful examination of every text referring to wine influenced many. Methodist minister Leon Field wrote in his temperance commentary, Oinos (1883), that at Cana Christ made grape juice because “no other is made, all else is manufactured. Nothing less than omnipotence could make one drop of the pure juice of the grape. The art of man can manufacture any amount of alcoholic wine.”

Temperance and abolition were often linked. Communion Wine and Bible Temperance (1869) by William Thayer (1820–1898) argues that the Bible is “a total abstinence Bible” and it had also taught “liberty just as much while slaves were held in bondage as since they were emancipated; but men did not see it.” Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), wrote in 1883 to Willard: “I feel that the Lord is with this movement and that he who came [to preach] deliverance to the captive will deliver those who are held in slavery by their own appetites and passions.” The causes were closely connected to female suffrage (another cause of Willard’s) too, with the assumption that women would vote to destroy the saloons that destroyed their families.

These reformers were convinced their work would bring a newer, more biblically faithful age in which God’s kingdom would come and his will be done. Frances Willard would not live to see the establishment of national Prohibition and women granted the vote in 1920. Had she been there, she might have told Charles Beard there is more than one kind of liberty. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is managing editor of Christian History and author of The Poisoned Chalice: Eucharistic Grape Juice and Common-Sense Realism in Victorian Methodism and Christian History in Seven Sentences.Next articles

Christian History timeline: Haunted by the word

Americans have translated, interpreted, applied, and wrestled with the Bible from colonial times to the 21st century

the editorsFrom revolutionary founder to founder of a Bible revolution

Elias Boudinot and his friends worked not only to begin a new nation but also to start the American Bible Society

Jonathan Den HartogGleams of truth

How American authors, believers and unbelievers alike, used the Bible in their work

Marybeth Davis BaggettSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate