Oh, freedom

[Douglass Inspiring the Youth of the Negro Race, by Cletus Alexander and Bruno Peiser, mural, 1933—Dayton Art Institute / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

A group of enslaved Black Christians gathered by the woods on a Sunday afternoon to hear a White preacher. Charles Colcock Jones (1804–1863) was three months into his grand project to bring the gospel to the enslaved. His listeners were generally receptive to the Princeton Theological Seminary graduate, who considered himself a “godly” slave owner. Jones’s morning sermon cautioned against idols, urging Blacks to abandon charms, sorcery, and “superstition.” This was well received.

In the afternoon, however, Jones preached about the runaway slave Onesimus. Despite the severe punishment his hearers risked for simply questioning a slave-owner, they protested his words which required runaway slaves to return to their masters as Christian obedience: “The doctrine is one-sided,” one told him after worship. “That is not the Gospel at all,” said another. “It is all [telling us not to] Runaway, Runaway, Runaway.” Some left during the service. Others told him they would never come to hear him preach again.

A fiery furnace

The reaction of this congregation in Liberty County, Georgia, reveals a critical feature of Black biblical interpretation: it was forged in the fiery furnace of slavery. From the Great Awakening in the 1740s through the nineteenth century, the overwhelming majority of Black Christians first came to faith through Methodist, Baptist, or Presbyterian evangelicalism. But the overwhelming majority of them also came to faith as enslaved people.

That meant that Black Christians simultaneously shared and departed from ways that White evangelicals understood the Bible and faith. Like White evangelicals they believed in the authority of the Bible, the significance of Christ’s atoning sacrifice, the necessity of conversion, and the importance of evangelism. (Jones had often preached on these subjects.) But Black Christians also prioritized a truth from the Bible that White evangelicals did not often emphasize or fully explore: God frees us from more than our sins.

The enslaved Black Christians who challenged Jones’s preaching that afternoon demonstrated the depth of that conviction. Every enslaved person knew from childhood what enslavers expected of them in terms of obedience. But in their eyes, something at the core of the faith was at stake. By declaring that “this is not the Gospel at all,” the dissenters did not claim that Jones simply held a different expression of the faith, as if he were a member of a different denomination. Instead they asserted that the preacher read the Bible wrongly.

Bound for the Promised Land

Exodus loomed large as the fundamental narrative of the Old Testament for enslaved Christians. It convinced them that leaving slavery was not “running away” from proper authority; it was escaping injustice. The numerous spirituals composed and revised by enslaved Christians reveal this understanding of the Bible.

To be sure, many spirituals speak of the redemptive power of Christ and identify with Jesus’s suffering. But a large portion of them sing of Moses, Pharaoh, the Promised Land, and the River Jordan. Harriet Tubman, who composed her own spirituals, sang “I’m bound for the Promised Land, on the other side of Jordan” within hearing of her puzzled enslaver the night before she fled slavery. She regularly sang of Egypt and Canaan while leading fugitives away.

Black Christians were drawn to a God who explained his character to the children of Israel by saying repeatedly, “I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery” (Exodus 20:2). Black Christians saw this deliverance as a critically important feature of God’s character and his plan for humanity. Those biblical themes continue to animate Black Christianity today.

This Black biblicism emerged in dialogue with, and in reaction to, a society dominated by Whites. Not only were 90 percent of African Americans in the early nineteenth century enslaved, they were vastly outnumbered by White Americans. In this social reality, White American Christians could easily deflect difficult questions that slavery raised for their faith.

A large proportion of northern White Christians considered slavery wrong but did not yet conclude from the Bible they ought to support abolition, which they viewed as a radical movement. Many nonenslaving Whites, North and South, justified slavery with simplistic readings of selective biblical texts.

Meanwhile Christian enslavers shaped the biblical message, consciously or unconsciously, to their interests because they controlled discussions with enslaved Christians. Until the issue came to a head in the Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian denominations in the 1840s, most Whites were not compelled to listen seriously to antislavery arguments from the Bible. After each of those denominations split over slavery, White southerners heard even fewer opposing interpretations.

“Pure, peaceable, and impartial”

But while Whites could ignore Black interpretations, enslaved people lived with the White Christian justification of slavery every day. And free Blacks were not free to ignore slavery. After all slavery was still legal in 1794 Pennsylvania when Richard Allen’s resistance to discrimination in Methodism led him to create a Black congregation that would later become the African Methodist Episcopal Church—the first independent Black denomination in the United States.

The liberating character of God that Blacks found in the Bible deeply informed abolitionist efforts. Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) stands as the most famous example of this. While still enslaved a teenage Douglass had a conversion experience at a Methodist revival near his plantation. In his first years of freedom in New Bedford, Massachusetts—before he wrote Narrative (1845) and launched out as an abolitionist speaker—he preached at the local African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

Throughout his life he quoted the Bible regularly and drew on biblical themes in his speeches and writings (see p. 11). His rhetoric did not pull any punches:

Between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference. . . . I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slave-holding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.

American Christians with little understanding of the experience of the enslaved often became quite defensive listening to this rhetoric. That was part of Douglass’s point. He believed one had to be made uncomfortable to see things more clearly. How could one call the United States a Christian nation, Douglass argued, if it sanctioned the sale of children away from their parents?

Even Charles Colcock Jones, despite his pledge to never break up a nuclear family, had sold a Black family to enslavers in New Orleans. While keeping the letter of his promise, he had separated parents from adult children, grandparents from grandchildren, uncles and aunts from nieces and nephews, and cousins from cousins, all left with no means of seeing each other again. Harriet Beecher Stowe, who had known Jones at Princeton, saw slavery’s corrupting effects on this Christian man. She used his writings to depict slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).

Black abolitionist David Walker (1796–1830) wrote just as forcefully as Douglass. “See how they treat us in open violation of the Bible?,” he argued in an 1829 pamphlet that surreptitiously circulated in enslaved communities. “An American minister, with the Bible in his hand, holds us and our children in the most abject slavery and wretchedness,” Walker declared. “Now I ask them, would they like for us to hold them and their children in abject slavery and wretchedness?”

Whites who turned to the book of Philemon to justify slavery failed to consider that Onesimus was not Black. Why, then, did Whites insist that only Blacks could be enslaved? Proslavery Christians remained blind to the reality that they were imposing their own racial categories on biblical texts, he argued.

Conversion and liberation

An African American Great Awakening swept through the South at the end of the nineteenth century. The number of Black Baptists in the United States increased from about 400,000 in 1860 to 2.2 million in 1906; Black Methodists from 190,000 in 1860 to more than one million in 1906. The estimated percentage of active Christians among African Americans rose from around 17 percent in 1860 to 42 percent in 1900.

Driven by Black evangelism and grounded in Black churches independent of White supervision, this produced a remarkable number of individual conversions to Christianity. But ideals of liberation also fueled this massive movement. Slavery, among other things, had denied religious freedom to Black southerners.

Some states had legally prohibited the ordination of Black ministers; most states had legally prohibited the enslaved from holding religious meetings without White supervision; and many enslavers would not allow the enslaved to hold religious services. A number of southern states had passed laws making it illegal to teach the enslaved to read and write, undermining a key Protestant conviction: the freedom to read the Bible for oneself. A few Whites defied these laws, some states permitted Black literacy, and some enslaved Blacks taught one another to read, but the vast majority had remained illiterate.

Abolition, however, opened tremendous opportunities for Black southerners to read the Bible for the first time. One elderly man in Mobile, Alabama, at the end of the war joined his grandson at a Black primary school newly created by missionaries. He told the teacher “he wouldn’t

trouble her very much, but he must learn to read the Bible and the Testament.”

Fueled by such passions, the Black church not only grew dramatically during the late nineteenth century but emerged as the foundation of Black community life. Independent Black ministers preached freely not only on personal transformation, but also on biblical themes of hope and liberation for the disinherited.

The Black community needed this sort of institution. Many Whites gave up on the “peculiar institution,” but not the underlying conviction that Whites ought to control society. Despite freedoms gained during Reconstruction in the 1860s and 1870s, African Americans faced tragic setbacks in the 1880s and 1890s.

White southerners stripped them of voting rights, solidified segregation, and began the vicious practice of lynching in the 1890s. After the turn of the century, southern Blacks who migrated to northern cities for a marginally greater set of opportunities often faced embedded prejudices and de facto segregation.

Plenty of “nice” people

In the first half of the twentieth century, liberationist biblicism continued to inform the Black church. Black Christians could not accept the assumption, held by many White Christians, that simply treating one another kindly would effectively address racial problems; plenty of “nice” people supported segregation.

Some southern church leaders began to see segregation as a problem by the early 1950s, but many actively supported it. Meanwhile many northern Whites passively ignored the issue and continued to deflect biblical arguments made by Black Christians.

Martin Luther King Jr.’s branch of the civil rights movement challenged this. Though he had adopted some new theological ideas in seminary, King (1929–1968) still drank deeply from the biblical fountains of his childhood Baptist church. The Old Testament particularly shaped his promotion of “prophetic Christianity”: though the just suffered and the unjust prospered, the arc of God’s activity through history would trend toward justice and hope.

At the grassroots level, Christians from Black churches formed the backbone of the civil rights movement, infusing it with traditional patterns of faith. Recruitment often resembled evangelistic campaigns. During the seminal 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, Ralph Abernathy and his assistants rounded up “sinners” in the bars and pool halls of the city to join churched Blacks in the boycott. At different times participants held prayer vigils, reported miraculous healings, and spoke in tongues. John Lewis (1940–2020) reported that some meetings resembled revivals.

King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” most clearly illustrates the biblical justification Black Christians made for ending segregation. Eight White clergy of Birmingham had published a letter to King arguing that King’s protests disrupted the peace, moved too quickly, and disobeyed the law. In response King justified his actions not only from great philosophers and theologians, but from the Bible, grounding his argument that unjust laws are no laws at all in the prophets, the life of Christ, and the story of the apostle Paul.

The White clergy of Birmingham thought they understood racism well enough. But King’s letter pushed them—and anyone who read it closely—to consider more deeply the Black biblical tradition. That tradition points to a God whose character not only promotes individual transformation, but liberation and justice. King challenged his White clergy brothers:

I have looked at the South’s beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?” CH

By Jay R. Case

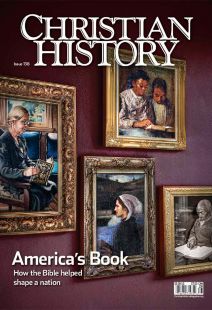

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

Jay R. Case is professor of history at Malone University and author of An Unpredictable Gospel.Next articles

From revolutionary founder to founder of a Bible revolution

Elias Boudinot and his friends worked not only to begin a new nation but also to start the American Bible Society

Jonathan Den HartogGleams of truth

How American authors, believers and unbelievers alike, used the Bible in their work

Marybeth Davis BaggettSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate