Preaching the holy war (Bible in America)

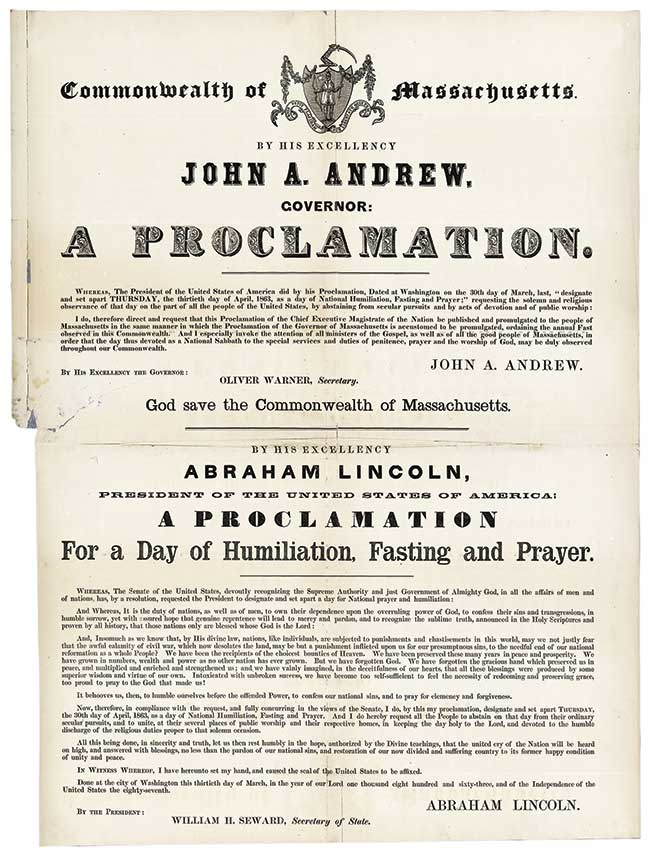

[Abraham Lincoln, “A Proclamation, for a day of national humiliation, fasting and prayer!” 1863—Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Alfred Whital Stern Collection of Lincolniana]

When the men in blue and the men in gray marched off to fight in 1861, they carried more than rifles and knapsacks. They took the blessing of ministers and other Christian leaders. Exceptions occurred, of course. Historic peace churches did not endorse the conflict, and disaffected people on both sides voiced dissent. On the whole, though, clergy in the North and South found scriptural grounds to ardently support their respective causes. American culture was drenched in biblical images; the ability of ministers to justify war in the name of the sacred book did much to mobilize popular support.

The new crusaders

When Lincoln’s 1860 election prompted Southern secession, Northern ministers advised caution. Some with strong abolitionist convictions argued this might prove a blessing, freeing the United States from the taint of slavery. More numerous Northern conservatives, some of whom sympathized with the South, hoped forbearance would bring seceded states to their senses. Reluctance vanished when Confederates opened fire on Fort Sumter in April 1861. Lincoln’s call to suppress the rebellion won nearly universal backing from Northern ministers. One noted: “If the crusaders, seized by a common enthusiasm, exclaimed, It is the will of God! It is the will of God!—much more may we make this our rallying cry and inscribe it on our banners.”

Preachers believed the hopes of humanity rested on the Union’s preservation; the United States‘ pure Protestant Christianity and republican institutions must remain models to the world. If the Union was destroyed, Baptist minister and educator Francis Wayland (1796–1865) argued, “crushed and degraded humanity must sink down in despair.” Many Yankee ministers thought Union soldiers were preparing the way for the Kingdom of God on earth. William Buell Sprague (1795–1876), editor of Annals of the American Pulpit, predicted Northern success would usher in “a flood of millennial glory,” “the great Thanksgiving Day of the World.”

But Southern clergy also viewed their cause as holy. Noted ministers called for secession. When conflict began clergy declared it to be a just war—and more. Confederates believed they bore a special mandate to set before the world ideals of ordered liberty, states’ rights, and biblical values. Religious leaders rejoiced that the Confederate constitution explicitly recognized the nation’s dependence upon God. One minister called the Confederacy “the Lord’s peculiar people.” Another wrote, “the pillar of cloud by day and fire by night was not more plain to the children of Israel.”

Many believed the Confederacy represented the future. Robert Lewis Dabney (1820–1898), theology professor at Union Theological Seminary and adjutant (assistant) to Stonewall Jackson, contended that the South would save the world from false ideas of “radical democracy.” Other preachers asserted that God might use the Confederacy to inaugurate his kingdom.

Baptism of blood

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and fundamentally altered the character of the war. Northern churches reflected—and in some cases, promoted—this shift. Initially most ministers were reluctant to support abolition, but the first few years of the war convinced them otherwise as the Army of the Potomac stumbled through successive defeats. They asserted that through this defeat of Union arms, God had punished the United States for slavery and signaled that the oppressed should go free.

With a few notable exceptions, Southern ministers believed that preserving slavery was an integral part of the Confederate mission: they argued God had ordained it as the most humane means of relating labor to capital, protecting Africans, and introducing them to the blessings of Christianity. “We do not place our cause upon its highest level,” wrote Episcopal bishop Stephen Elliott (1806–1866), “until we grasp the idea that God has made us the guardians and champions of a people whom he is preparing for his own purposes and against whom the whole world is banded.” Sermons and art frequently invoked images of contented, loyal slaves.

Some ministers demanded an end to laws prohibiting slave literacy and limiting ministerial preaching, for these kept African Americans from the gospel. Similarly reformers desired statutory recognition of slave marriages and families. Such proposals never became law, but won favorable comment from some Southern ministers who argued that God would not bless the Confederacy until it made bondage fully humane.

Presidents Davis and Lincoln designated various fast days for repentance during the war, and Northern and Southern clergy often named surprisingly similar transgressions: intemperance, Sabbath breaking, greed, unrestricted individualism, and lack of loyalty to authorities. Although clergy sometimes used fast days to condemn the enemy, generally each side reflected on its own sins. Presbyterian minister and Southern plantation owner Charles Colcock Jones (1804–1863) wrote to his aunt: “We have been sinning with the Northern people as a nation for seventy or eighty years, and now we have become two nations, and the Lord may use us as rods of correction to each other.”

Protestants hoped the war might wash the nation clean, albeit through bloodshed. In the South Presbyterian pastor James H. Thornwell (1812–1862) warned “our path to victory may be through a baptism of blood.” B. T. Lacy (1819–1900), Episcopal chaplain to the Stonewall Brigade, declared: “Baptized in its infancy in blood, may [the Confederacy] receive the baptism of the Holy Ghost, and be consecrated to its high and holy mission among the nations of the earth.” On the Union side, Congregational pastor Horace Bushnell (1802–1876), shortly after Bull Run, told his parishioners more humiliation and suffering must purge America’s dross: “tears in the houses, as well as blood in the fields.” But once the ordeal passed, he predicted, the United States would become “God’s own nation.”

For Northern clergy this blood baptism received final ritual enactment when an assassin struck down Abraham Lincoln on Good Friday, 1865. The president’s death symbolized reparation for national sins: “He has been appointed . . . to be laid as the costliest sacrifice of all upon the altar of the Republic and to cement with his blood the free institutions of our land.”

Lost cause and legacies

Long after guns fell silent, some ministers still sounded battle cries. Prominent Congregationalist Theodore Munger (1830–1910) continued to interpret the war as God’s righteous retribution on the wicked South. Southerners such as Dabney nursed grudges against Yankees and longed for “retributive providence” to obliterate the Union.

But most Southerners admitted that preservation of the Union had been for the best. Over the next decades, though, they celebrated Confederate memorial days, erected statues of the fallen, and produced an outpouring of literature, surrounding the defeated South with an aura of sentimental nobility. Advocates of the Lost Cause converted Confederate warriors into pious men reluctantly taking up arms; in a haze of moonlight and magnolias, they transfigured them into romantic heroes with virtues appreciated even by former enemies.

Many clergy wished to bury the acrimony of the past; in the process both church and society often trivialized or obscured deeper moral issues. African Americans paid the price. Victor and vanquished tacitly agreed to end Reconstruction without securing political rights for formerly enslaved people, who soon faced epidemic lynching, the gutting of civil-rights legislation, and the creation of Jim Crow laws. Surely this outcome fell far short of the moral rebirth that Protestants had hoped would follow their baptism of blood. CH

By James H. Moorhead

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

James H. Moorhead is Mary McIntosh Bridge Professor of American Church History emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary and author of American Apocalypse: Yankee Protestants and the Civil War, 1860–1869. This article is adapted from a longer one in Christian History issue 33.Next articles

Christian History timeline: Haunted by the word

Americans have translated, interpreted, applied, and wrestled with the Bible from colonial times to the 21st century

the editorsFrom revolutionary founder to founder of a Bible revolution

Elias Boudinot and his friends worked not only to begin a new nation but also to start the American Bible Society

Jonathan Den HartogSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate