From revolutionary founder to founder of a Bible revolution

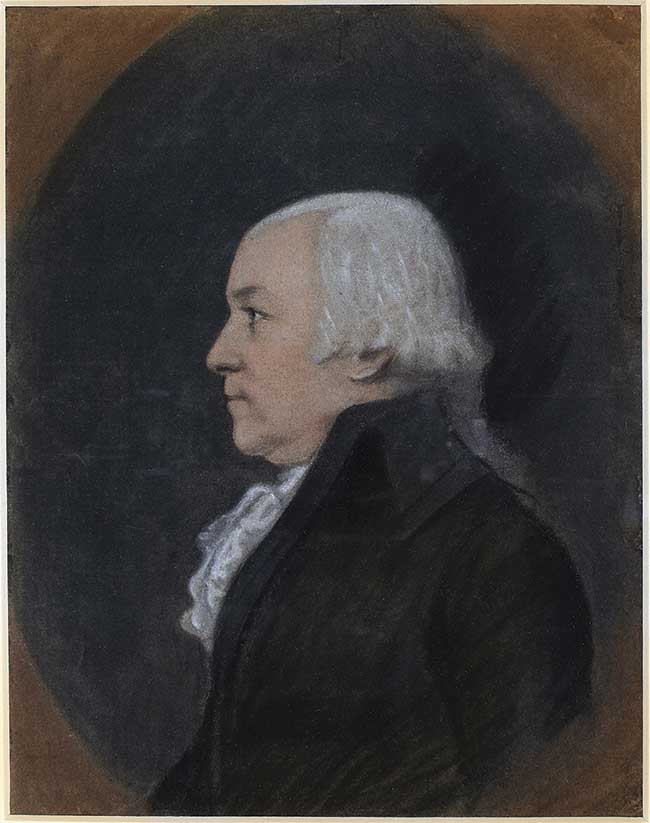

[Elias Boudinot IV, by James Sharples. Pastel, before 1811—Princeton University Art Museum / [Public domain] Wikimedia]

Who was the first President of the United States? If you answered “George Washington,” you are right—sort of. Before the Constitution was adopted in 1789, fourteen men served as presidents of the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War and under the Articles of Confederation. Long after the articles lay covered in dust, a different work occupied two of those “first presidents,” Elias Boudinot and John Jay—promoting the place of the Bible in the new nation.

“Sincere thanks”

Elias Boudinot (1740–1821) grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, and was baptized as a Presbyterian by the great evangelist George Whitefield. He chose a career in law, joined the New Jersey bar in 1760, and soon married Hannah Stockton; they had one child, Susan. The outbreak of the American Revolution afforded him wider opportunity to serve; he was elected to the New Jersey Provisional Congress as a Patriot (those who wanted to separate from England, as opposed to Loyalists who wanted to remain). As fighting raged across New York and New Jersey, General Washington called on Boudinot to serve as commissary of prisoners, visiting prisoners of war to see that they were receiving necessary supplies—a difficult task, as many were kept in prison ships in New York Harbor. In 1778 New Jersey sent him to the Continental Congress; in 1782, as its president, he officially received the Treaty of Paris ending the war and guaranteeing American independence.

Boudinot’s neighbors elected him to the US House of Representatives, where he served for three terms. He advanced several pieces of faith-informed policy: most dramatically, the first national Thanksgiving in 1789: “an opportunity to all the citizens of the United States, of joining, with one voice, in returning to Almighty God their sincere thanks for the many blessings he had poured down upon them.” The House named Boudinot as one of those to carry the suggestion to President Washington. Washington agreed and issued the call for a national Thanksgiving.

Boudinot also raised his voice as an early opponent to the trading of enslaved persons. The Constitution prohibited immediate outlawing of such trade, but he still argued that Congress should listen to petitions asking for its end, which he saw as a clear moral and Christian imperative.

Reason vs. revelation

Boudinot’s retirement from government in 1801 opened up opportunities for Christian service. One of his first efforts was a defense of the Scriptures. In the mid-1790s Thomas Paine had shifted to writing about religion; his book The Age of Reason (1794) strongly critiqued Christianity and the Bible in particular. Although many wrote responses to Paine, Boudinot penned one of the most developed, The Age of Revelation (1801).

Soon Boudinot grew deeply invested in the work of Bible societies. Here three factors converged. First, Americans were developing greater interest in voluntary societies—independent organizations devoted to a specific purpose—as powerful mechanisms for social and religious improvement. Second, they already had an example from Britain—the British and Foreign Bible Society—to emulate. Third, Bible societies provided a way for Christians to influence society positively by distributing the Scriptures broadly.

In 1809 Boudinot helped found the New Jersey Bible Society and served as its president. After several years he pushed for a national Bible society. In the middle of the War of 1812, he and the New Jersey society issued a call for a national convention. They received pushback, but Boudinot responded that the task was simply too large—an entire nation needing Bibles!—for any local society to accomplish. A national society could coordinate local and state efforts and use economies of scale. This approach would mirror the federal Constitution—a national structure that united and multiplied the effects of many smaller bodies.

By 1816 the time was right. With the War of 1812 concluded, the public mood was optimistic, entrepreneurial, and nationally minded, and Boudinot found allies in the Jay family of New York. John Jay (1745–1829), a devout Episcopalian and student of the Scriptures, had been the first chief justice of the US Supreme Court, a key American diplomat, and New York’s governor. John’s son William (1789–1858) was a Yale-educated lawyer and an energetic reformer; he truly supported the vision of a national society and began working with Boudinot to make it happen.

President again

The group’s founding convention met in New York City in May 1816. Boudinot was home sick in New Jersey, but William Jay, the dynamo at the center of the event, kept him well informed. Jay led the committee in drawing up a founding constitution, following the model he and Boudinot had been promoting. As first president the convention selected—naturally—Boudinot.

The ABS founding met with significant approval. Prominent ministers such as Jedidiah Morse (1761–1826) and Lyman Beecher (1775–1863, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe) gave their blessing. Many prominent national political figures also signed on in support, including John Jay, Governor Caleb Strong of Massachusetts, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina, Supreme Court Justice Bushrod Washington of Virginia (George Washington’s nephew), and Congressman Felix Grundy of Tennessee.

And the work of the ABS prospered. It immediately set out to spread the Scriptures (published “without note or comment”) throughout the rapidly expanding United States; partnering with affiliated societies, it gave members an opportunity to think nationally but act locally. Being interdenominational, it encouraged cooperation between Christians of various stripes even while advancing a Protestant appreciation for the individual soul encountering the unfiltered Word of God.

Meanwhile the national organization headquartered in New York City devoted itself to efficiently producing Bibles sold at extremely low costs across the country; it probably had a larger reach than the federal government. It also developed new printing techniques to bring costs down through mass production.

In short it was the prototype for an effective voluntary organization. Overseeing the launch of this endeavor was Boudinot, who served as president until 1821 (he was followed by no less a luminary than his friend John Jay). Every year he gave a presidential address, celebrating the work of the ABS and spurring the organization on to greater efforts. He believed the ABS effort was not just significant, but world-changing, and hoped it would stick to its mission until the world was evangelized and Christ returned.

Today the ABS (headquartered in Philadelphia since 2015) publishes the Good News Translation of the Bible, distributes Bibles in over 700 languages, and is even in charge of an internet extension (.bible). In these and other modern ways, it tries to fulfill the goal Boudinot once set forth in a presidential address: “rearing a national superstructure of Heavenly charity, that will last we hope, till every region of the earth shall be enlightened by the Sun of Righteousness.” CH

By Jonathan Den Hartog

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

Jonathan Den Hartog is professor of history and chair of the History Department at Samford University and author of Patriotism and Piety: Federalist Politics and Religious Struggle in the New American Nation.Next articles

Gleams of truth

How American authors, believers and unbelievers alike, used the Bible in their work

Marybeth Davis BaggettSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate