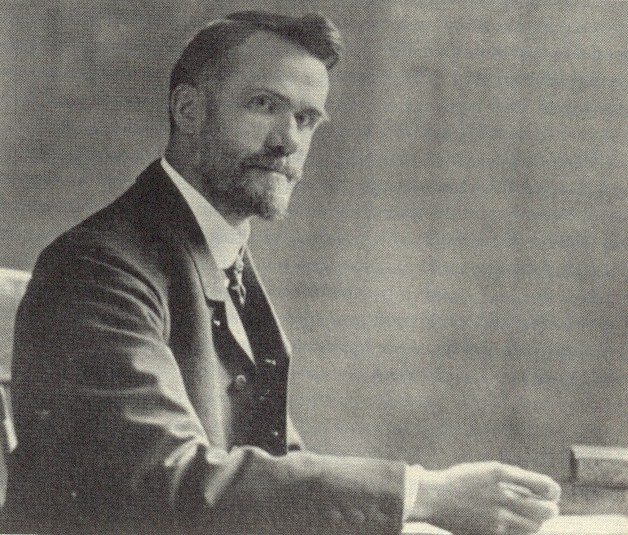

WALTER RAUSCHENBUSCH’S SOCIAL GOSPEL WAS TEPID ON DOCTRINE

[Above: Walter Rauschenbusch—public domain because of age / Wikimedia]

AT THE BEGINNING of the twentieth century, one of the best-known names in American theology was Walter Rauschenbusch. His book Christianity and the Social Crisis (1907) was a bestseller by comparison with most theology books.

The son of German immigrants, Rauschenbusch studied in both the United States and Germany. He became the pastor of Second German Baptist Church in the Hell’s Kitchen area of New York City. The oppressed and desperate lives of that neighborhood woke his social conscience. He rejected capitalism and embraced Fabian socialism, then a relatively new movement. Before Rauschenbusch died on this day, 25 July 1918, apparently without hope of bodily resurrection, his works had reached the height of their popularity.

Rauschenbusch’s teaching stressed the importance of social action. In this he was following the lead of recent predecessors such as the Wesleys, the Booths, Charles Finney, slavery abolitionists, alcohol prohibitionists, and other religious reformers.

He would declare,

Christ’s conception of the kingdom of God came to me as a new revelation. Here was the idea and purpose that had dominated the mind of the Master himself.... It responded to all the old and all the new elements of my religious life.

Although Rauschenbusch claimed to be an evangelical who sought to win people to new life in Christ, his driving motivation was to transform earth into the Kingdom of God through social and political means. In order to make the case for the preeminence of social action, he found it necessary to abandon longstanding doctrines of orthodox Christianity.

In his last major work, A Theology for the Social Gospel, Rauschenbusch flatly denied the doctrine of imputation, calling it “post-biblical.” He also denied hell as a place of eternal punishment, rejected the Bible’s apocalyptic teachings and its belief in demons and a literal devil. He cast doubt on the bodily resurrection of people and, despite the Bible’s emphasis on Christ’s Resurrection as central to the gospel, Rauschenbusch’s Theology was silent about that significant event.

An adherent of German critical theories, Rauschenbusch argued that theologians had to decide which Bible teachings were to be retained by moderns and which were outdated. Even the words of Christ were to be accepted only if theologians considered them authentic and not later additions. Because of his divergences from orthodox doctrine, many theologians declared his teachings heretical.

Nonetheless the concerns of Rauschenbusch and kindred thinkers were part of the social consciousness that helped bring about political reforms that eased the condition of workers and immigrants, and demanded the breakup of powerful, coercive monopolies.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For another notable proponent of the social gospel, read "The life and times of John Bascom" in Christian History #104, Christians in the New Industrial Economy

The social gospel also receives discussion in "The needs of the worker" in Christian History #141, City of Man