The Meaux Circle and the Holy Triumvirate

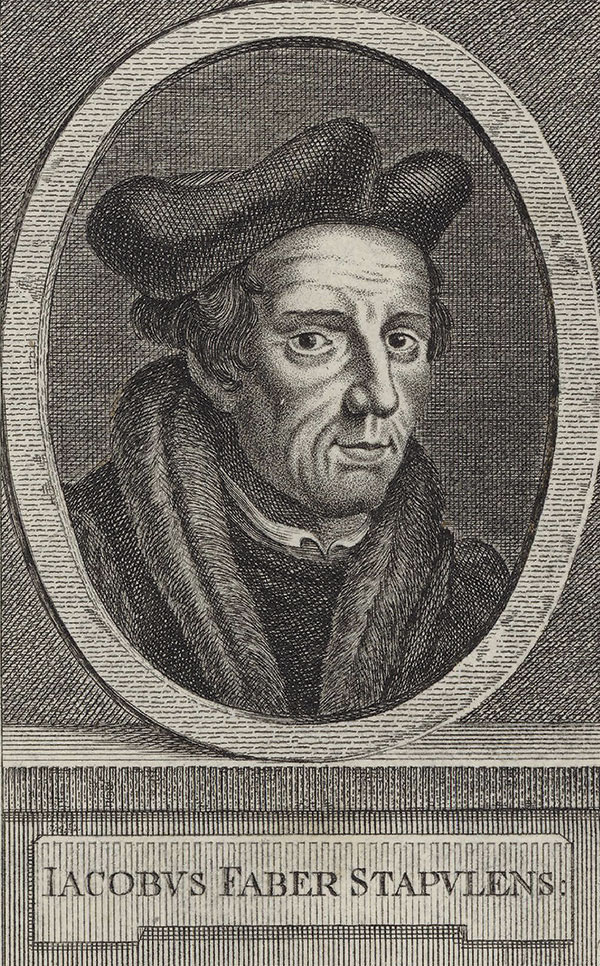

[Iacobus Faber Stapulens, Emmanuel Eichel, National Library of France (Public domain)]

SOMETIMES FRIENDSHIPS ARE FORGED in the furnace of trials. Such was the case with many who labored to reform the church in France in the circles connected to King Francis I’s sister, Marguerite de Navarre, in the early decades of the sixteenth century (see CH #131 for more).

These evangelicals (as they called themselves) were Renaissance humanists; their interests lay in a return to ancient sources, which they believed possessed truth that had been buried for centuries. They read ancient texts by Christian writers like Justin Martyr, Tertullian, and Augustine and also by pagan authors like Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero. They regarded all of this material as of the utmost significance, and it would contribute to their rediscovery of the gospel.

Circle of reform

Chief among these circles was a group of colleagues that arose in the city of Meaux in the first few decades of the sixteenth century. Sometimes called the Circle of Meaux (le cénacle de Meaux), this group included Guillaume Farel (1489–1565), Antoine Froment (1508–1581), Marie Dentière (c. 1495–1561), Jean Le Comte de La Croix, Gérard Roussel, Pierre Caroli, Clément Marot, and many others.

As it grew the Circle developed into a pervasive reforming subculture within French Catholicism—a subculture that spread across much of France. They spread their reform with the aid of Marguerite, who had evangelical leanings herself and was their principal and most powerful patron.

The Circle of Meaux owes its beginnings to Bishop Guillaume Briçonnet (c. 1472–1534). Prior to his move to Meaux, he had worked to reform the abbey of St Germain des Près outside of Paris. Once he arrived in Meaux and began reform work, he called on friends to assist him. In 1521 he asked his former teacher Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (c. 1455–1536) for help. Lefèvre, known in Latin as Faber Stapulensis, was a brilliant biblical interpreter and theologian. He had already made a name for himself and was embroiled in a series of controversies over his novel ideas concerning biblical exegesis. He would play an extremely important role within the Circle of Meaux.

Lefèvre had become an admirer of Martin Luther in 1520. Luther’s reformation of the German church had commenced in 1517, and by 1520 he was working aggressively to fight doctrinal corruption and introduce the gospel into the Catholic Church. Lefèvre, Briçonnet, and other members of the Circle of Meaux became increasingly supportive of Luther’s endeavors and set themselves to advance the true Evangel (i.e., the gospel) throughout their French homeland.

Following Luther’s lead they put in place a robust and innovative program of biblical instruction. Inspired by Luther’s 1522 German New Testament translation and his sermon collections, Lefèvre produced a French New Testament the next year. His famous translation of the Psalms also followed in 1524. He wished these to be available to all men and women in France. Briçonnet paid for Lefèvre’s Bible translations to be published and distributed them for free to the laity.

The Meaux group also gave daily Bible lessons on the Psalms and on Romans to the more spiritually advanced men and women in the church. In 1525, based on their preaching and on Lefèvre’s biblical exegesis, members of the group published a book of sermons in French. Their humanist interests and intense devotion to ancient learning—and particularly ancient texts and all things Greek, Hebrew, and Latin—found perfect expression in these text-based efforts to bring change to what they regarded as a morally corrupt and doctrinally bankrupt French Catholic Church.

Invariably their pursuit of reformation brought the Meaux group into conflict not only with the French Catholic authorities but also with one another. Francis I had early on exhibited broad support for humanist learning, resulting in a relatively benign attitude toward the Meaux Circle. Yet his attitude began to change in the 1520s and into the 1530s, when he became more inclined to turn against these evangelicals if they sought their aims with greater vigor.

With the church and the king against the Circle of Meaux, the Paris Faculty of Theology joined the fray. These scholars had opposed Briçonnet, Lefèvre, and the Meaux group from the early 1520s onward but had been thwarted in doing anything about it. Now they were free to pursue members of the group and began seeking to have them arrested.

In November 1533 Nicholas Cop, newly appointed rector of the University of Paris, gave an address that smacked of Lutheranism—at least, in the judgment of the Sorbonne (as the University of Paris was commonly called). This address led to numerous arrests, including the attempted capture of John Calvin.

The opposition did not deter them. In October 1534 a group associated with Marguerite de Navarre’s evangelical network posted placards all over Paris, and in a few other cities such as Tours and Orléans, denouncing the Roman Catholic Mass as idolatry. The authorities responded aggressively and executed several people believed to have been involved in perpetrating the act. From then on Francis I’s attitude toward evangelicalism and the Meaux group hardened.

A cord of three strands

Despite their trials the Circle’s influence extended and took root in a younger generation, most notably through Farel and his friendship with Calvin and another young evangelical, Pierre Viret (1511–1571). Calvin would later write when he dedicated his commentary on Titus to Farel and Viret: “It will at least be a testimony to this present age and perhaps to posterity of the holy bond of friendship that unites us. I think there has never been in ordinary life a circle of friends so heartily bound to each other as we have been in our ministry.”

Viret, 22 years younger than Farel, was born in Orbe, Switzerland, and came to France to begin studies for the priesthood at the University of Paris. He adopted evangelical beliefs during his studies around 1527 and may well have met Farel in Paris; both he and Farel were back in Orbe in the early 1530s. They both left rather quickly for fear of persecution, winding up in Geneva in 1534, but also traveling frequently over the next decade.

Farel encouraged Viret to begin preaching prior to their arrival in Geneva. He would do the same for Calvin, another young protégé, when Calvin made his way to Geneva in 1536 intending only to stay for one night.

Reluctant prophet

As the well-known story sets out, Farel went to Calvin’s room that night and urged him to stay to work for reform in Geneva. Calvin by this time had become famous as the author of the Institutes of the Christian Religion and declined Farel’s request on the grounds that he preferred quiet study. Farel pronounced upon Calvin the damnation of God if he did not stay. In a letter written much later to his friend Martin Bucer, Calvin alluded to the calling of the reluctant prophet, Jonah, as he recounted the event: this was, in other words, God speaking to him through Farel. Calvin felt compelled to heed the terrifying words he had heard.

By 1538 Calvin and Farel had both been expelled from Geneva for a complex collection of reasons—related, in part, to the stubbornness of a city not ready for change and also to the overbearing brashness of the two men, who tried to impose reform too hastily. Calvin went to Strasbourg and Farel to Neuchâtel.

But after the expulsion, Farel and Viret (who had by this time become a pastor in Lausanne) almost immediately began working to bring Calvin back to Geneva. The effort was emotionally exhausting, particularly for Calvin. He wrote letters to both Farel and Viret in which he agonized over the issue. “It would,” Calvin wrote to Viret, “be more preferable to perish for eternity than to be tormented in that place [Geneva].”

The efforts of Viret, Farel, and others (like Bucer) eventually prevailed, and Calvin moved back to Geneva. Having been mentored by Bucer in Strasbourg, Calvin returned to Geneva more spiritually mature and ready to work more intelligently for reform in the city. He also returned married to Idelette de Bure, whom his friends in Strasbourg had urged him to wed.

Farel stayed in Neuchâtel for the remainder of his life, dying in 1565. He outlived Calvin by only one year. Viret helped Calvin in Geneva for some months; Calvin wrote to Farel at one point, “If Viret leaves me, I am completely finished; I will not be able to keep this church alive. Therefore, I hope you and others will forgive me if I move every stone to ensure that I am not deprived of him.”

In 1542 Viret returned to his church in Lausanne, but he continued to correspond with his friends; Calvin even introduced him to his second wife, Sebastienne, after his first wife died. Viret outlived both his friends, dying in 1571.

While Calvin and Viret wrote to one another, both could count Farel as their strongest influence. His enormous impact on the two men led Bucer to nickname the three a “Holy Triumvirate.” The letters Farel wrote to his younger protégés are full of spiritual nourishment and, not infrequently, vehemence. He was willing to say what needed to be said, even when it was difficult.

His insistence upon firm and sure words bore fruit—both in the maturing of Calvin and Viret into formidable theological and pastoral minds and also in terms of the spread of the gospel around France, Europe, and the world. C H

By Jon Balserak

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #132 in 2019]

Jon Balserak is senior lecturer in early modern religion at the University of Bristol. He is the author of numerous books including John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet and Calvinism: A Very Short Introduction.Next articles

“A pure and holy love”

“On Spiritual Friendship” was a popular medieval expression of what it meant to be a friend to other believers

Aelred of Rievaulx“Our single object and ambition was virtue”

Spiritual friendship among the Cappadocians

Megan DeVoreSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate