“From sea to shining sea”

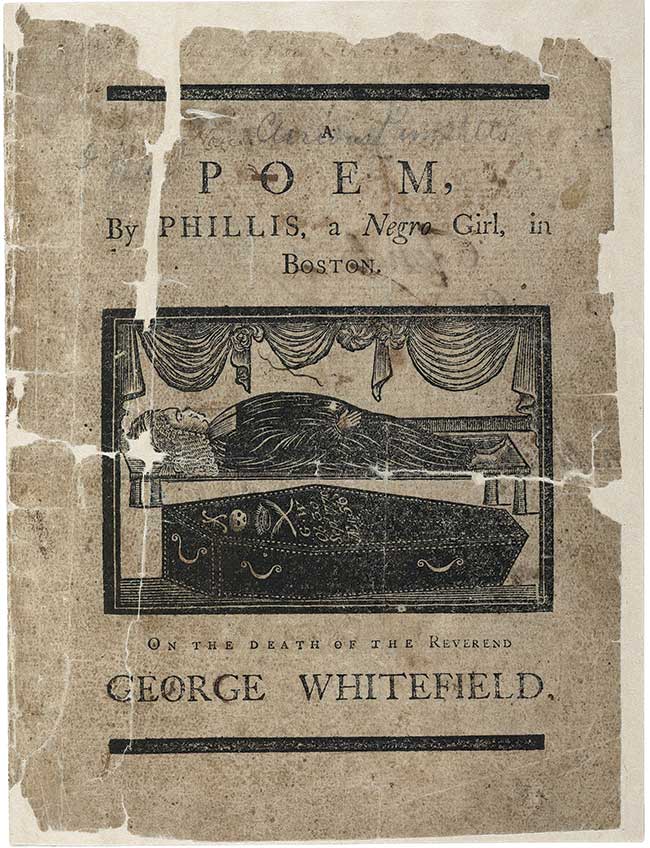

[Phillis Wheatley, An Elegiac Poem, 1770—American Imprint Collection / Library of Congress]

William Penn (1644–1718)

Born in England to famed admiral Sir William Penn and his wife, Margaret Jasper, William Penn grew up Anglican. But when plague drove the family to their estates in Ireland, the teenage Penn began attending Quaker meetings. Arrested for his Quaker affiliation, he was sprung from jail because of his father’s prominence, but the admiral sent his son packing without an inheritance.

Penn then began to write pamphlets full of scriptural references touting the truth of Quakerism and the corruption of other denominations, and questioning traditional doctrines such as the Trinity. By 1668 Penn was in the Tower of London for his religious convictions.

Eventually admiral and son reconciled; Penn regained his inheritance and became a royal counselor. In this capacity he proposed that English Quakers immigrate to the Americas. In 1677 a group of them purchased half of what is today New Jersey. Four years later Charles II gave Penn a large swath of land west of New Jersey (Pennsylvania, or “Penn’s woods,” named after Penn’s father).

Penn worked to create in this settlement a religious sanctuary not only for beleaguered Quakers, but also for Huguenots, Mennonites, Amish, Catholics, Lutherans, and Jews—all refugees. Though a believer in the power of God’s Word, Penn wrote in 1673 of the potential danger in people reading the Bible without Christ’s light in them: “That the Scriptures are Unintelligible without it [the Inner Light] is easily prov’d from the variety of Judgments that are in the World about most of the Fundamental Doctrines contained therein.” (Read more about Penn in CH 117, The Surprising Quakers.)

Cotton Mather (1663–1728)

Cotton Mather was born in Boston to a famous pastoral family; his father, Increase Mather (1639–1723), and both his grandfathers, John Cotton and Richard Mather, were prominent Puritan ministers. In 1685 Mather took over his father’s duties as pastor of Boston’s North Church. The younger Mather was a prolific writer, producing more than 450 books and pamphlets; he encouraged colonists (now two to three generations removed from England) to maintain Puritan roots instead of moving toward a more watered-down Protestantism.

Mather helped instigate the Salem Witch Trials and reported on them; he wrote, “If . . . the publication of these Trials may promote such a pious Thankfulness unto God, for Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Re-joyce that God is Glorified.” In the years following, Mather continued to believe in the possibility of witchcraft, but he denounced the loose legal standards that had allowed the trials to explode. He was also a supporter of the day’s progressive science and encouraged the controversial movement to inoculate against smallpox (see CH 135, Plagues and Epidemics).

Mather recognized that previous biblical interpretation would not satisfy a world full of new discoveries in cosmology and science. Instead of avoiding the conversation, he actively engaged in cultural discussion to promote the continued relevance of God’s Word. One of his numerous unfinished works was the Biblia Americana, which he considered his masterpiece and worked on from 1693 until his death in 1728. In it he encouraged Christians to interpret the Bible in such a way that philosophy, science, and religion work together to create a fuller picture of God and his mysterious ways.

Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753–1784)

Phillis Wheatley, the first published Black woman in America, was captured in West Africa and sent via slave ship to America when she was only seven. The Wheatley family of Boston purchased her and brought her up as a domestic servant in their household. Against prevailing norms they taught her to read and write and also guided her theological training. By the time she was 10, she could translate Greek and Latin classic literature into English, and by age 16, Wheatley had become a Christian. She began to use her learning, faith, and literary skill to persuade fellow Christians of the humanity of enslaved Africans, writing:

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

She also began referring to herself as an “Ethiope” to reclaim that biblical term for Black and African people, citing Moses’s Ethiopian wife (Numbers 12:1). To counter Christian justifications of slavery, Wheatley argued that enslaving people is antithetical to the message of Christ. She compared American slaveholding to pagan Egyptian slavery, something White Christians would have understood to be evil.

Wheatley negotiated her freedom in the mid-1770s. She continued to use her literary voice to challenge important cultural leaders (including George Washington and George Whitefield) in their support for slavery. However, life was difficult for her as a freed woman, and Wheatley died in obscurity and poverty at the age of 31. She is remembered for her fierce intellect and her focus on the biblical story to denounce slavery and promote true social change.

William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925)

William Jennings Bryan’s Baptist father was a prominent Illinois judge and Democrat while his mother was Methodist; they determined to let their son choose his church affiliation. Bryan had a conversion experience at 14 during a revival, which he remembered as the most important moment of his life; as a result he joined the Presbyterian Church. A gifted student and orator, he decided to follow his father into law.

Bryan ran for Congress in the 1890 election, winning as a populist and progressive Democrat. In 1896 and 1900, he was the Democratic presidential nominee but lost both times to William McKinley (1843–1901). Following his second presidential defeat, Bryan founded a weekly newspaper, The Commoner, which became one of the most-read newspapers in the country. Again Democratic presidential nominee in 1908, he lost to William Howard Taft (1857–1930). He later served as secretary of state for Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924).

After 30 years in politics, Bryan focused more directly on religion, concerned with the erosion of biblical literalism in Protestantism. He also worried that Darwin’s theory of evolution contradicted the Bible and would lead to unregulated Social Darwinism, affecting women’s suffrage and workers’ rights: “There has not been a reform for twenty-five years that I did not support, and I am now engaged in the biggest reform of my life.” In 1925 he took part in the Scopes Trial concerning a substitute teacher who violated Tennessee’s Butler Act by teaching evolution. (See CH 55, The Monkey Trial and the Rise of Fundamentalism.) The media criticized Bryan as scientifically uneducated, but he maintained that “science is a magnificent material force, but it is not a teacher of morals.”

Carl McIntire (1906–2002)

The son of a Presbyterian minister, Carl McIntire was raised by his mother in Oklahoma following his father’s mental breakdown and his parents’ divorce. A talented debater and a natural leader, McIntire decided to follow his father into ministry by entering Princeton Theological Seminary. Because he disliked liberal elements at Princeton, however, he soon transferred to the newly established Westminster Theological Seminary and graduated in 1931.

Ordained in the Presbyterian Church USA, McIntire took a church in 1933 in Collingswood, New Jersey; he would remain there for the rest of his life. Just as in seminary, McIntire took sides between fundamentalist and modernist factions within the PC (USA), helping to found a conservative alternative to the more liberal Board of Foreign Missions. Tried in ecclesiastical court over this, he joined other conservatives to create the Orthodox Presbyterian Church in 1936. However, because of infighting, he then left in 1937 to form the Bible Presbyterian Church. Distinctives included abstaining from alcohol and tobacco, using the Scofield Reference Bible, and adhering to premillennial eschatology.

Both times McIntire left a denomination, the bulk of his congregation accompanied him; when they lost their beautiful Gothic property, they worshiped under an outdoor tent before eventually constructing a new church building that dwarfed their original home. McIntire also founded the weekly newspaper The Christian Beacon; a daily radio show, “The Twentieth Century Reformation Hour”; and summer Bible conferences, and he helped create the American Council of Christian Churches.

McIntire considered himself a pastor and teacher passionate about the Bible. He proudly called himself a fundamentalist, defining this as someone who adhered to the historical Christianity of the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Nicene Creed, and the Apostles’ Creed. Remembered even among friends as someone who caused and even sought division as well as one who conflated politics and religion, McIntire would have said he lived out 2 Corinthians 6:17: “‘Come out from them and be separate,’ says the Lord. ‘Touch no unclean thing, and I will receive you.’”

John McConnell (1915–2012)

The grandson of a Pentecostal preacher who came to faith at the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 and the son of founding members of the Assemblies of God in 1914, John McConnell began to develop a concern for God’s creation during his work in plastic manufacturing in the late 1930s. He saw how much creating plastics hurt the environment, and he began to focus on environmental and peace causes. He moved to California to work on peace efforts, which culminated in a 1962 campaign called “Meals for Millions” to feed refugees from Hong Kong.

His interest in and concern for environmental health was born out of his understanding of Psalm 115:16: “The highest heavens belong to the Lord, but the earth he has given to humankind.” In 1969 he suggested the creation of Earth Day to focus on the beauty of Earth and the promotion of world peace. The first celebration took place March 21, 1970, and after adoption by the United Nations in 1971, it has been celebrated annually on the spring equinox around the world (including by those who never knew of its Christian origins). McConnell always saw Earth Day as an opportune time for Christians “to show the power of prayer, the validity of their charity, and their practical concern for Earth’s life and people.” CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #138 in 2021]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a freelance writer and editor. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history.Next articles

Questions for reflection: The Bible in America

Questions to help you think more deeply about this issue

the editorsRecommended resources: Bible in America

Learn more about the history of the Bible in America with these resources selected by Christian History’s authors and editors.

the editors and authorsHallowed Halls: Did you know?

This issue shares many stories about colleges and universities trying to pursue human flourishing. Here are a few to start you off.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate