Imitating Christ

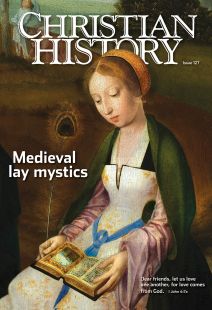

[Thomas à Kempis sits in front of the monastery he made famous; at left the artist has placed à Kempis’s

17th-c. admirer, Arnoldus Waeijer. Courtesy of http://www.peperbus-zwolle.nl/pagina/thomas]

It’s been cited as an influence on everyone from Thomas More to Thomas Merton, John Wesley to John Newton. Over 2,000 editions have been printed around the world. Its popularity rivals the Bible and Pilgrim’s Progress—in fact only the Bible has been translated into more languages. The heart of its message is the theme of conversion: “Turn to (Converte te) the Lord with all your heart, forsake this sorry world, and your soul shall find rest.”

What is it? It’s the little book The Imitation of Christ, which emerged from the pen of an initially obscure priest in his forties who was participating in an early fifteenth-century revival. Who was Thomas à Kempis, and how did his book come to take the Christian devotional life by storm?

a life unclean

To answer that question, we must step back about 80 years before the Imitation burst on the scene. By the late Middle Ages, a number of experimental forms of religious life were emerging across Europe, some successful and some less so. One of the most successful experiments was the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, the so-called Devotio Moderna (Modern-Day Devout, as the rest of this article will call them), who sought to appropriate in their age (moderna) the piety (devotio) of Christians from earlier days.

Flourishing primarily in the Low Countries, this movement can be traced to fourteenth-century churchman Gerard or Geert de Groote (d. 1384). De Groote was born in 1340 in Deventer, now in the Netherlands.

Orphaned at age nine, de Groote made his way to France where he earned a master’s degree and served at the University of Paris. In his mid-twenties, he studied law and obtained ecclesiastical benefices (what we would now call church stipends) in Aachen and Utrecht, making a career out of conducting business for the church.

But by 1374 de Groote considered his life “unclean” and in need of a conversion. He resolved to “order his life” and soon turned his house in Deventer into a hospice for the dying and resigned his benefices. He also began a reading program that ranged from the Gospels to the lives and sayings of the Desert Fathers. He spent time with Carthusian monks (an order that had been founded about 300 years previous by Bruno of Cologne) but chose not to join any particular religious order.

De Groote was living the kind of religious life already being practiced by thousands of women who had collectively come to be called Beguines (see “A spiritual awakening for the laity,” pp. 6–12). Many of these women for different reasons could not become “normal” nuns—quite a few could not afford the entry “dowry” required by many monasteries—so they lived as recluses, serving in hospices, alms-houses, and other places.

In time these women moved into houses together called beguinages, mostly in cities, so that they could engage in communal contemplation of God away from the distraction of others. Different houses had different practices, but many Beguines chose to live chaste, virginal lives coupled with voluntary poverty and ongoing penitential acts.

The Beguines were neither in nor out: not proper members of religious orders nor fully laypeople. This was a new form of the Christian life that occasionally received papal approval but at the same time drew the ire of many churchmen and city councils. De Groote was in the same boat. Soon others joined him.

In September 1374 de Groote gave use of his house to some poor women. Five years later he drew up a constitution for the now-growing community, clearly stating that this was neither the beginning of a monastic order nor a beguinage. Rather he sought to provide a place for Modern-Day Devout women to worship God peacefully and to be free to come and go as God led them, though once they left they could not return.

These women remained members of the local parish church like all laypersons. They wore no distinctive dress, and those who sought to join this society did not need to live at de Groote’s house. Instead they could become members while living in their own households.

For the community to run properly, two women were appointed matrons, overseeing the finances and communal discipline when necessary. Thus began the Sisters of the Common Life.

About the same time that de Groote was setting up the Sisters’ constitution, a man named Florentius (or Florens) Radewijns (d. 1400) moved to Deventer to be near de Groote, having heard of de Groote’s fame as a preacher. De Groote’s early male followers met in Radewijns’s residence, and some of them lived together in his house.

In time these male followers merged their finances and made de Groote their leader and teacher, founding the Brothers of the Common Life. As he had for the women, de Groote drew up a set of rules including a schedule for the men’s daily tasks and religious exercises.

Before his sudden death from the plague on August 20, 1384, de Groote, concerned for the men’s temporal possessions, advised that those fit for the monastic life should found a monastery; those not called to the monastic life could remain in the “world,” under the protection of the newfound community. When asked what kind of monastery they should found, de Groote recommended the Augustinians, as their rule was not as harsh as those of the Carthusians and Cistercians.

Father of the Devout

Radewijns became director of the community in 1384, coming, in time, to be seen as the “father and patron of the Devout.” His house in Deventer continued as the center of the movement, but following de Groote’s deathbed direction, Radewijns oversaw the foundation of an Augustinian house of canons (priests who lived together under a rule of religious life) in 1386. With episcopal approval he selected a site at Windesheim and dedicated a chapel and basic buildings in October 1387.

This new religious order gained approval from Rome in May 1395, formally establishing the Windesheim Congregation of canons and, in time, canonesses—reaching at its height approximately 100 houses with about 2,000 members.

Enter Hammerken

This milieu attracted a young man named Thomas Hammerken (c. 1379–1471). Born in Kempen (which is why we now call him “à Kempis”), near Düsseldorf in the Rhineland, at the age of 13 he joined his older brother John at a school run by the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer. In 1399 he moved into the Brothers’ house in Zwolle.

However the Brothers also had a home in Mount-St.-Agnes, strategically positioned outside the town away from noise and distractions. There Thomas made his final profession in 1407 and was ordained a priest just a few years later at around age 34.

In addition to his more famous works, Thomas would eventually write The Chronicle of the Canons Regular of Mount St. Agnes, providing a history of the monastery up to his death in 1471. In fact Thomas devoted his life in the monastery primarily to writing, preaching, and copying manuscripts (including a copy of the Bible), though he also served briefly as subprior and novice master.

He became the author of a number of devotional and spiritual works including Prayers and Meditations on the Life of Christ, Meditation on the Incarnation of Christ, The Elevation of the Mind, On Solitude and Silence, On the Discipline of the Cloister, The Soliloquy of the Soul, Concerning the Three Tabernacles (a treatment of poverty, humility, and patience), and On True Compunction of Heart. He also wrote biographical works on de Groote, Radewijns (who was Thomas’s spiritual father), and a number of early Modern-Day Devout “fathers.”

Thomas’s most influential work, however, remains The Imitation of Christ, written in Latin in the 1420s; it was first fully translated into English by Richard Whytford in 1556. Thomas’s authorship of The Imitation has been debated since the publication of the first printed edition at Augsburg in 1471, but most scholars today have concluded that Thomas authored the work (as opposed to other possible candidates such as de Groote, Jean Gerson, Bernard of Clairvaux, and Walter Hilton).

The book is heavily indebted to the thought and influence of Augustine of Hippo and Bernard of Clairvaux—not to mention the Bible: it includes more than 1,000 direct biblical references. It began as four different pamphlets meant for use in Modern-Day Devout houses.

The first part (“Admonitions Useful for Spiritual Life”) presents a call to conversion, directed especially to young students. The second section (“Admonitions Drawing to Things Inward”), says that the end of a converted life depends on constructing an “interior person,” becoming a “person of peace” so focused on self and God as to be unmoved by what goes on around one. The third (and longest) part, “On Inward Consolation/Solace,” continues the theme of peace from the second part, and the fourth and final section, “Blessed Sacrament,” discusses the Eucharist. The book is subdivided into a total of 114 chapters.

The Imitation was likely intended as an instruction manual for young novices because it considers topics of special importance to the followers of the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life: religious devotion, humility, denial of the world, silence, and meditation on the sufferings of Christ.

The work also serves as a brief manual on the monastic life—especially a kind of interior monasticism, in which outward appearance does not make the monk, but rather “the transformation of one’s way of life” characterizes the true monk and separates him from the false monk. This harmonizes with Thomas’s conviction that one’s “inner goodness” is always more important than one’s outward behavior, since God searches the heart.

live like the angels

Because the canons of the Windesheim Congregation were priests, Thomas took time to address their specific concerns. He insisted that the priest’s “life should not be like that of worldly men, but like that of the Angels.”

Likewise he understood God’s admonition to “Be holy as I am holy” (1 Peter 1:16) to be directed particularly to priests. Perhaps because he was a priest, Thomas was a strong advocate of frequent Communion, believing that infrequent reception resulted in “sloth and spiritual dryness.” For those unable to commune in person, Thomas promoted a “spiritual communion with Christ.”

The main theme of the work, nonetheless, was a topic close to the heart of everyone involved with the Modern-Day Devout: how to practice spiritual disciplines while remaining in the world, most often as a layperson. Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life held in balance a tension between those members of the community who remained in the cities (either in Devout homes or in their own homes) and those who became Augustinian canons and canonesses. They were exceptional; no other late medieval movement blended so well monastic and lay forms of the Christian life.

The Imitation is an excellent example of the kind of spiritual writing that bridges these two forms of life. Though it is relevant to novice canons and canonesses and to priests, it is exceedingly practical for lay readers as well. Thomas believed that only the “true, inward lover of Jesus and the Truth . . . can turn (convertere) freely to God, rise above self, and joyfully rest in God.” Conversion is the first and necessary step on the pilgrimage to God, for when one converts, he “loses his sloth and becomes transformed into a new creature.” Without a conversion there is no spiritual progress.

This conversion is not simply an intellectual assent to propositional truth claims, nor is it merely submission to the fact of one’s baptism. No it is a conversion away from one’s self by looking into one’s self: “the deeper [a man] descends into himself the lower he regards himself, the higher he ascends toward God.”

Radically Thomas asserted that a person must annihilate himself or herself to receive the grace of God: “If you know to annihilate yourself perfectly and to empty yourself of every created love, then I [Christ] may grow into you with great grace.” For Thomas conversion was a momentous turning away from oneself and toward God.

At the same time, he thought that one must also turn from the “wretched world,” the so-called created loves—not just from the material things of the world, but also from vain, worldly learning and from pride. In life,

Man is defiled by many sins, ensnared by many passions, a prey to countless fears. Racked by many cares, and distracted by many strange things, he is entangled in many vanities. He is hedged in by many errors, worn out by many labors, burdened by temptations, enervated by pleasures, tormented by want.

He added,

The weakness of sinful human nature will at times compel you to descend to lesser things, and bear with sorrow the burdens of this present life.

In short the “inner life of man is greatly hindered in this life by the needs of the body.” Thus, to draw close to God, Thomas argued that the disciple must crucify the desires of the flesh and “lament the burden of the body,” asking God to “make possible . . . by grace what is impossible . . . by nature.” For who is “more free than she who desires nothing upon earth”?

things that bring Peace

Lastly, Thomas thought, one who wished to imitate Christ must enjoy the rest given by God. Thomas identified four things that bring peace and tranquility of soul: 1) to do the will of others, not one’s own will; 2) to possess less rather than more; 3) to take the lowest place and regard oneself less than others; and 4) to desire and pray for God’s will to be perfectly fulfilled in you.

As the disciple descends into herself, she cares less for the things of the world and finds great consolation in the things of God, and this consolation brings peace. For a disciple “who is free from inordinate desires, can turn freely to God, rise above self, and joyfully rest in God.”

Many were hungry for this message. Not only did Thomas’s writings spread like wildfire, but the entire movement transformed thousands of lives. Scholar John Van Engen believes that the Windesheim Congregation was “the most successful new religious order in the fifteenth century.” If true it is because the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life offered the kind of religious life that those converted to Christ in the Low Countries were seeking: a brilliant arrangement that allowed men and women, monastics and lay, to coexist and benefit from each other’s unique charisms.

The Modern-Day Devout continue to offer a model to twenty-first-century Christians of how to pursue God wholeheartedly. They give the church a paradigm for holding together the many different ways in which Christians seek to make spiritual progress. There is much to learn from this late medieval work of God’s Spirit. CH

By Greg Peters

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #127 in 2018]

Greg Peters is an associate professor at Biola University in the Torrey Honors Institute. He is the author of The Story of Monasticism: Retrieving an Ancient Tradition for Christian Spirituality and coeditor of Marking the Church: Essays in Ecclesiology.Next articles

The agony and the ecstasy

catherine of siena invited others into a passionate, physical devotion

F. Tyler SergentA medieval mystic untimely born?

In Brother Lawrence the desires that had motivated medieval mystics found fresh expression.

Kathleen MulhernThe fires of love

From the highest nobility to the lowest working class, medievals heard the call of God over four centuries.

Matt ForsterSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate