"A little thing like a nut"

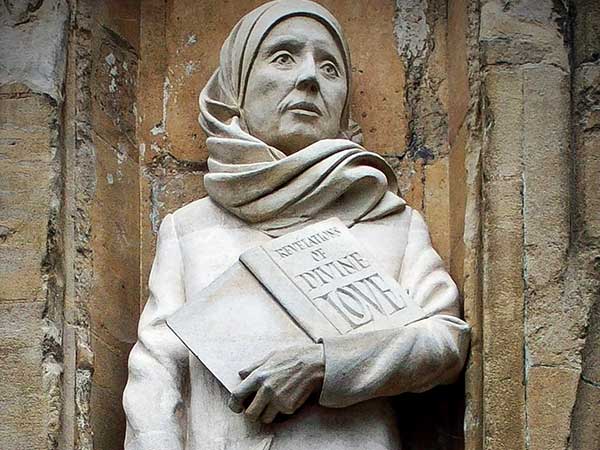

[Statue of Julian of Norwich by David Holgate, west front, Norwich Cathedral—Poliphilo / Wikimedia]

In the flourishing late medieval town of Norwich, a small room known as an anchorite’s cell is built onto the parish church of St. Julian. A number of medieval churches had such “cells” attached.

The anchorites who lived in these cells were usually female (often called anchoresses) and had taken vows to spend their lives in solitude and prayer. While they attempted to withdraw from the world, they lived in the heart of the community and thus often became centers of pilgrimage and sources of spiritual advice.

The most famous of the late medieval anchorites lived in this cell next to St. Julian’s Church; she succeeded in obliterating her original identity so completely that we know her only as “Lady Julian of Norwich” after the parish church. Yet “Julian” (c. 1342–c. 1416) was not only a famous spiritual advisor in her own day—people traveled miles to see her—but is known to posterity as one of the greatest spiritual writers in Christian history.

Her fame rests on a single book, existing in a longer and a shorter version: the Showings or Revelations of Divine Love (c. 1395). This book, written down by a male cleric, records a series of visions Julian received during a severe illness.

look toward the cross

Julian’s visions, like many others in the late Middle Ages, focus on a graphic portrayal of the physical sufferings of Christ. But what makes Julian’s book so remarkable is the vivid and radical way she draws out the implications of Jesus’s sacrificial love for the nature of God. At one point, tempted by a “friendly suggestion” in her heart to look away from the cross that appears in her vision, she responded by saying to the crucified Jesus, “You are my heaven.”

This is why Julian refers to Jesus as “mother,” a move that endears her to modern feminists. (Like many other elements of her spirituality, this wasn’t entirely new; medieval mystics from the twelfth century on often referred to Jesus this way.) For Julian this wasn’t a rejection of traditional masculine language, but rather a dramatic way of highlighting Jesus’s nurturing love as central to God’s character. One of her most memorable metaphors, summing up her spirituality—literally—in a nutshell, is her vision of the whole universe as “a little thing like a nut” held in the protecting and nurturing hand of God.

Julian has been understood as a universalist based on her repeated statement that her visions revealed “nothing about hell” and her insistence that “all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.” She always said that she adhered to church teaching on damnation, but she clearly struggled with reconciling this teaching with the unconditional love of God; the closest she came to resolving this tension was claiming that God will “do a deed” at the end of time that will be unimpeded by human sin.

I first encountered Julian’s writings in a college class on medieval mysticism, and they have been one of the most powerful spiritual influences on me ever since. I find in Julian a rich, imaginative, and profoundly orthodox presentation of the heart of the Christian faith, all the more compelling because she is so thoroughly medieval even as she transcends so radically the flaws and limitations of much of medieval popular piety.

When modern “progressives” tell me that God is all love, they are saying what their culture requires them to say if they are to be respectable believers at all. But when a medieval ascetic, shut up in a tiny cell attached to a stone church, has lurid visions of the discolored body of Christ on the cross, and on the basis of those visions tells me that the self-giving, all-forgiving love of Jesus is the ultimate truth about the universe . . . then I dare to believe that it just might be true.

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #127 in 2018]

Edwin Woodruff Tait, contributing editor, Christian History. A shorter version of this article appeared in CH #116.Next articles

A medieval mystic untimely born?

In Brother Lawrence the desires that had motivated medieval mystics found fresh expression.

Kathleen MulhernThe fires of love

From the highest nobility to the lowest working class, medievals heard the call of God over four centuries.

Matt ForsterMedieval mystics: Recommended resources

Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors to help you understand medieval mystics and their world.

The issues authors and editorsGeorge Müller, Did you know?

Enjoy these classic stories of george Müller and his influence from Delighted in God by Roger Steer

Roger SteerSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate