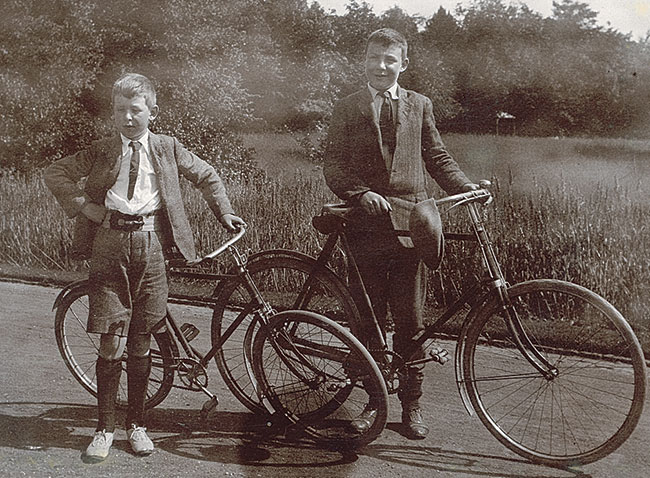

Friends and brothers

[Above: Lewis brothers posed with bicycles in front of the Ewart family home, Glenmachan, which neighbored their own home, Little Lea, August 1908. Used by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL]

Jack Lewis’s lifelong friend and compatriot was his brother, Warren Hamilton (Warnie) Lewis (1895–1973). Warnie wrote, “I first remember him, dimly, as a vociferous disturber of my domestic peace and a rival claimant to my mother’s attention.” However, Warnie and Jack soon “laid the foundations of an intimate friendship that was the greatest happiness of my life and lasted unbroken until his death.” Warnie also had his own career as a military man and author. Their life together spanned two distinct periods: the Belfast or Little Lea era in childhood, 1898–1914, and the Oxford or Kilns period from 1932 to Jack’s death in 1963.

A piece of paradise

The Lewis brothers grew up in Northern Ireland, the only children of Albert J. Lewis, a Belfast solicitor, and Flora Hamilton Lewis, daughter of their parish priest, whose BA in mathematics and logic from Queen’s University, Belfast, was distinctly unusual for the times (see pp. 20–23). Jack mischaracterized Albert and Flora Lewis in Surprised by Joy, giving the impression that they were perfunctorily religious when in fact the Lewis parents read the Bible together daily and were deeply pious, active Christians.

The Lewises lived from 1894 to 1905 in Dundela Villas, Belfast, where both sons were born. Belfast was very rainy, and medical wisdom of the day deemed damp weather harmful, so the Lewis brothers spent a good deal of time indoors reading and eventually writing. They soon created their own imaginary countries, India and Animal-Land. However, their stories about these countries were surprisingly prosaic—containing not “the least hint of wonder,” Jack said later—and were nothing like the later Narnia.

Warnie and Jack also shared several deep aesthetic experiences, including one related to a toy garden Warnie created (which gave the boys a vivid “imagination of Paradise”) and another of looking at the Castlereagh Hills (the Green Hills) which were visible from their bedroom windows, “not very far off, but . . . quite unattainable.” Lewis later characterized this feeling of longing as “Joy.”

In 1905 the family moved to “the New House” or Little Lea, a home that Albert built for Flora. In an oft-quoted passage from Surprised by Joy, Lewis described the New House as “almost a major character in my story . . . long corridors, empty sunlit rooms, upstairs indoor silences, attics explored in solitude . . . [and] endless books.” No wonder the Lewis brothers were bookish all their lives; lists of books Warnie and Jack were reading frequently appear in the Lewis Family Papers. Little Lea also had a splendid view of the Belfast Lough, the Antrim Mountains, the Holywood Hills, and a northwestern prospect of “interminable summer sunsets behind blue ridges,” all of which further contributed to the boys’ imaginative development.

Warnie Lewis went to an English boarding school in 1905, though his absence apparently made no difference to the bond the two boys shared. For Warnie and Jack, this schooling was merely an inconvenient separation between golden days of summer. Their earlier countries were now merged into Animal-Land, lifted out of the real world into an imaginary universe, complete with an intricate political history, historiography, and geography with detailed maps (they shared this interest in imaginative cartography with Tolkien). They later called this fictional world “Boxen.”

The great continent sunk

Change soon came; the untimely death of Flora Lewis in 1908 at the age of 46 shattered this idyll. Her death had a traumatic impact on her 13- and 9-year-old sons. Jack later wrote: “With my mother’s death all settled happiness, all that was tranquil and reliable, disappeared . . . the great continent had sunk like Atlantis.” The equally devastated Albert Lewis was left to single-parent adolescent boys, a trying task in the best of circumstances, and one made more difficult by Albert’s approach to life.

Soon alienated from their father, the two boys took to making fun of Albert behind his back, as Surprised by Joy abundantly illustrates. Jack wrote later:

By a peculiar cruelty of fate, during those months the unfortunate man, had he but known it, was really losing his sons as well as his wife. We were coming, my brother and I, to rely more and more exclusively on each other for all that made life bearable; to have confidence only in each other.

Albert worked from nine to six daily, and his absence from the home further estranged him and his sons. When the brothers were at home, they developed “a life that had no connection with our father,” including their imaginary world in which he had no place.

In 1908 the brothers reunited at Warnie’s English school, Wynyard, a place so bad Jack later called it Belsen (after the Nazi concentration camp). The headmaster was later certified insane, and the school was closed in 1910. In 1909 Warnie moved on to Malvern College. There, in contrast to his brother, the gregarious Warnie thrived, made many friends, and even developed an academic sideline—writing papers for his classmates. He also seems to have lost whatever childhood faith he had. The brothers reunited again when Jack joined him in 1911 at a boarding school in the same town.

After finishing at Malvern in the fall of 1913, Warnie embarked on a cram course with his father’s teacher, W. T. Kirkpatrick (see p. 27). The unexpected result was his election to a prize cadetship at Sandhurst (the British West Point) in 1914. After this training he served in France during World War I as part of the Royal Army Service Corps. The brothers’ childhood together was officially over. Though they occasionally met on vacations, Warnie’s career separated him from Jack for most of the next two decades, taking him to Sierra Leone, China, and various home postings.

In 1929 Albert Lewis passed away shortly after retiring. The next year Warnie and Jack, now a professor at Oxford, visited Little Lea for the last time. They buried their Boxen toys in the garden and packed up the (extensive) family papers. The income from the sale of Little Lea provided the means to buy a new home for the Lewis brothers, as well as for Mrs. Janie King (Minto) Moore and her daughter, Maureen (whom Jack had supported since World War I; see p. 35).

In July 1930 the expanded Lewis family first saw what was to become their new residence, The Kilns, in Headington Quarry, Oxford. Warnie noted in his diary that the spacious grounds of The Kilns (which included a large pond and was adjacent to an extensive woods) were “such stuff as dreams are made of,” and Jack wrote “I never hoped for the like.” Ten days later their offer to buy The Kilns was accepted, and in October Warnie helped Jack and the Moores move in.

Walking and editing

In 1931, while in Asia, Warnie Lewis returned to the Christian faith at about the same time as Jack was completing his pilgrimage from atheism to theism to Christianity. With Warnie’s retirement from the military and move to The Kilns in 1932, the Lewis brothers began the second major phase of their life together, which lasted until Jack’s death.

The new arrangement had mixed effects. On the one hand, Warnie’s diary is full of accounts of cultural activities, including going to concerts and plays and listening to recorded classical music. On the other hand, life with Mrs. Moore grew increasingly disagreeable as time passed and the family became increasingly dysfunctional. She demanded more and more of Jack Lewis’s time as her personality deteriorated (she was 26 years older than Jack), became progressively more self-centered, and, as an outspoken atheist, was not at all pleased with the Lewis brothers’ turn to religion.

However, Warnie had other outlets that provided respite from the quarrelsome atmosphere of the Moore-dominated life at The Kilns. He was occupied with his editing of the Lewis Family Papers; he also continued research into the French Grand Siècle (the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV) and split his time between his study at The Kilns, his brother’s rooms at Magdalen College, and the resources of the Bodleian Library. He took numerous walking tours with his brother and with some of the Inklings. And he acquired a motorboat, The Bosphorus, which he had built for cruising on Great Britain’s extensive inland rivers and canals.

“Evasive as Mr. Badger”

Warnie and Jack Lewis’s major social activity was the weekly gathering of the Inklings, who began meeting Thursday evenings in Lewis’s rooms at Magdalen College sometime in the 1930s. They drank and socialized, engaged in academic banter and exchanged literary subtleties, and listened to one another read works in progress. The group also met by a warm coal fire on Tuesday mornings for more of the same in a back parlor called the Rabbit Room at Oxford’s Eagle and Child pub—which they called “the Bird and Baby.”

Though Jack Lewis and Tolkien generally dominated the discussions, the irenic Warnie, modestly hovering in the background—“evasive as Mr. Badger”—provided the invisible social glue that held the group together. John Wain (1925–1994)—an English poet Jack had tutored—described Warnie as far from being a silent cypher; instead, he was “a delightful man with a very well-stocked mind, tolerant, generous, imaginative, with a great sensibility . . . deeply read, very gifted in verbal expression.”

The Second World War brought additional adjustments for the Lewis household. On September 2, 1939, the first set of evacuee children from London came to stay at The Kilns (see pp. 41–43). Maureen Moore married Leonard Blake (d. 1989) in 1940 and left. Warnie was briefly recalled to active service and was among those evacuated from Dunkirk. He returned to Oxford for what would be the most fruitful and productive era in the history of the Inklings, as Charles Williams (1886–1945) became a major influence on the group.

Warnie also began to function as his brother’s secretary, necessitated by the deluge of correspondence that C. S. Lewis was now receiving as a result of his BBC lectures and the publication of The Screwtape Letters (1942).

The end of the war in 1945 was supposed to be a celebratory moment for the Lewis brothers and the Inklings, but things turned out otherwise. Less than a week after VE Day, Williams unexpectedly died, and some of the air went out of the group. They continued to meet for several years, listening primarily to Tolkien’s reading of drafts of The Lord of the Rings, but the Thursday evening meetings came to an end in 1949.

The problems of the Lewis household were also multiplying; Jack’s letters and Warnie’s diaries were increasingly full of negatives about the tenor of family life at The Kilns. Warnie had always consumed too much alcohol, but he now slipped into chronic alcoholism, including frequent binge drinking. An episode in the summer of 1947 left him hospitalized for over a month.

By 1947 Moore was so ill she could not leave home; she moved to a rest home in 1950, where Jack, although himself unwell, visited her every day until her death in early 1951.

“Many merry days”

With the Moores gone, life at The Kilns shifted from stressful to peaceful, quite in keeping with the Lewis brothers’ professed love of sameness and monotony. However, in 1952 something new intruded into Jack and Warnie’s Acadian bachelorhood. An American correspondent and avid reader of Jack’s writing, Joy Gresham (see pp. 36–39), visited Oxford. Warnie wrote that her “intentions were obvious from the outset.” Her relationship with Jack gradually grew from friendship to romance and culminated in their marriage in 1957, even as she was dying of cancer.

Warnie first met Joy in 1952 and “was some little time in making up my mind about her,” but soon “a rapid friendship developed; she liked walking, and she liked beer, and we had many merry days together.”

Later he wrote that Joy was rarely “equaled as a conversationalist” and that her “company was a never-ending source of enjoyment.” They also shared an interest in French history. Jack, for his part, said in a letter, “Warnie is my dearest and closest friend, and I can never be sufficiently thankful for the way in which he accepted my marriage.”

When Joy received a cancer diagnosis, Warnie was devastated for both her and his brother. He found the situation “heartrending . . . though to feel pity for any one so magnificently brave as Joy is almost an insult . . . why, one asks, should J[ack] have had the life which has been his . . . and then the prospect of ‘peace at eventide’ so cruelly snatched away.” When Joy died in 1960, Warnie wrote: “God rest her soul, I miss her to a degree which I would not have imagined possible.”

The literary community owes Warnie a debt of gratitude for his prolific writing. His research and writing on France culminated in his first book, The Splendid Century, in 1953; he added six others between 1954 and 1962. He also kept his diary until his death in 1973; along with the Lewis Family Papers that he compiled and a 1966 memoir essay about Jack, the diary constitutes one of our most important sources on C. S. Lewis and the Inklings. He later regretted that he had not “Boswellized” his brother and the Inklings more deliberately (as eighteenth-century author James Boswell had tracked the life of his friend Samuel Johnson).

On November 22, 1963, just shy of his sixty-fourth birthday, Jack Lewis passed away from multiple organ failures. Warnie wrote:

In their way, these last weeks were not unhappy. Joy had left us, and once again—as in the earliest days—we could turn for comfort only to each other. The wheel had come full circle: once again we were together in the little end room at home, shutting out from our talk the ever-present knowledge that the holidays were ending, that a new term fraught with unknown possibilities awaited us both.

They were “brothers and friends” to the end. On the tombstone of their joint grave site in Headington, Warnie had engraved the words from Shakespeare’s King Lear that had appeared on the Lewis family calendar on the date Flora Lewis died: “Men must endure their going hence.” On April 9, 1973, Warnie too went hence and was buried with his brother. CH

By Paul E. Michelson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Paul E. Michelson is distinguished professor of history emeritus at Huntington University.Next articles

“Romantic and realistic”

The eventful life, marriage, and death of Joy Davidman Lewis

Abigail Santamaria“At our level”

Lewis was a loving correspondent, godfather, and friend to the children in his life

Joe RickeSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate