“Romantic and realistic”

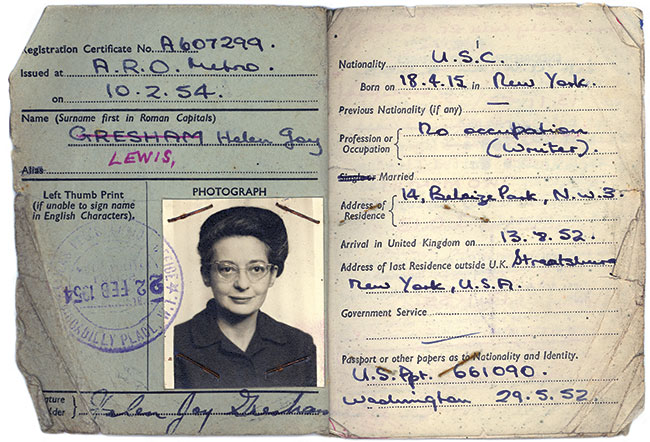

[Above: Davidman's residency permit shows the change in her last name. Joy Davidman, English registration document with photo, February 1954, CSL-F/P83. Used by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL]

Helen Joy Davidman (1915–1960) is best known today as the feisty but wounded American-born “Wife of C. S. Lewis” of Shadowlands fame. But the real Joy was a successful writer in her own right—and far more accomplished, brilliant, manipulative, and complicated than history remembers.

A poetic temperament

Born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan to Eastern European Jewish immigrants, Davidman was raised in a comfortable middle-class Bronx neighborhood by parents who had toiled to escape the poverty-riddled tenements of their youth. Her mother, Jeannette, was a college-educated kindergarten teacher; her father, Joseph, earned a PhD and became a New York City public school principal.

Desperate to assimilate, the Davidmans held Joy and her younger brother, Howard, to exacting standards. Joseph demanded academic perfection, while Jeannette emphasized outward appearances, grooming her daughter meticulously and criticizing her harshly for gaining weight in adolescence. Though IQ tests proved her brilliance, Davidman’s teenage rebellion took the form of neglecting disliked schoolwork and wearing dowdy, clashing clothes, to her mother’s dismay.

A sickly child, unpopular at school and unhappy at home, she escaped into voracious reading. She had a passion for fantasies, especially George MacDonald’s; the three-dimensional world “bored” her. Despite what she later recognized as a “cocksure” persona, her poetic temperament sensed spiritual reality. But coming of age in depression-ravaged America and disillusioned by World War I, she did not believe in God.

Davidman graduated from high school at age 14 and enrolled at Hunter College, part of the then-tuition-free City University of New York, where she had the freedom and guidance to nurture her love of writing poetry and prose. She paid little attention to politics and had no direct experiences with financial hardship until trauma occurred on Hunter’s campus in her final semester, spring 1934. She witnessed a classmate from an adjacent building leap several stories to her death; the girl was a starving orphan, her family devastated by the Great Depression. This set Davidman on a path of disillusionment with capitalism and preoccupation with communism, particularly the Spanish anti-Fascist cause. Her poetry evolved into political activism. In 1938 she became a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

By then she had earned a master’s degree in literature from Columbia and taught high school English, a job she despised. Her parents insisted it was the sensible professional path; she had other ambitions. Prestigious national journals including Poetry and the Marxist New Masses published her poems. Her first book, Letter to a Comrade (1938), was honored with a Yale Younger Poets prize (see p. 40).

Circle of comrades

By age 25 Davidman had published a novel, Anya (1940), done a Hollywood stint in MGM’s Young Screen Writers program, and joined the editorial staff of New Masses. Remaining loyal to the CPUSA despite a mass exodus following a nonaggression pact between Hitler’s Germany and the Soviet Union, she taught poetry at the Jefferson School, a Marxist CPUSA adult education institute, and participated in panels, symposia, and ceremonies with American cultural figures.

Her circle of comrades included dapper, folk-singing pulp fiction writer William (Bill) Lindsay Gresham (1909–1962), an American veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, a band of volunteers who fought Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Gresham nursed deep psychological battle wounds: anxiety, paranoia, nightmares, alcoholism, and a history of suicide attempts. Yet Davidman was drawn to his charm, intelligence, humor, and politics. They married in 1942 and moved to the suburbs shortly after David Lindsay Gresham (1944–2014) was born. Douglas Howard (b. 1945) soon followed. Consumed by motherhood and isolated, Davidman drifted from the Party.

In the suburbs she desperately missed New York City’s intellectual, creative stimulation and felt confined to homemaking. In this disorienting milieu of war, loneliness, and identity crisis, books served as a mechanism of self-preservation. She escaped into fantasy, particularly by newly popular British author C. S. Lewis; it “stirred an unused part of my brain to momentary sluggish life,” she later wrote. “Of course, I thought, atheism was true, but I hadn’t given quite enough attention to developing the proof of it.”

Under the strain of fatherhood, Gresham’s drinking and depression accelerated. Financial troubles followed. One day he disappeared. Terrified he might have taken his life, Davidman fell to her knees in prayer. “All my defenses—the walls of arrogance and cocksureness and self-love behind which I had hid from God—went down momentarily,” she wrote. “And God came in.”

When Gresham returned safely two days later, she was no longer an atheist and not even agnostic: she knew God existed, though what that meant she didn’t yet understand. Together she and Gresham began methodical religious study. Lewis’s works influenced them toward Christianity.

But trouble was far from over. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, their financial situation became desperate. Gresham relapsed repeatedly into heavy drinking. Davidman battled to reclaim some semblance of a career, but her second novel was poorly received. They turned to Dianetics, a dangerous but popular new self-help trend through which they believed recovered life-shaping prenatal memories. They also both wrote to Lewis.

Bill Gresham soon lost interest, but the “pen-friendship” of Joy and Jack intensified. Though dramatically different personalities from disparate cultures, they had much in common, from an early love of George MacDonald to a passion for intellectually rigorous verbal sparring. Lewis was one of few who could trounce Davidman in debate, an experience she relished; Davidman could out-argue him, too, and he greatly respected her mind.

Till We Have Faces

This emotionally and intellectually satisfying relationship heightened Davidman’s awareness of Gresham’s shortcomings. She began to fantasize about Lewis and commenced a series of passionate sonnets expressing her desire for him and her determination to win his love. In 1952 she left her boys with Gresham and Renée Rodriguez, a cousin who was living with them, and sailed to England. During her five-month visit, she fell more deeply in love with Lewis. While he did not return her affection, he resoundingly enjoyed her companionship and the keen editorial mind she lent to his works-in-progress, including proofs of English Literature in the Sixteenth Century for the Oxford History of English Literature series (abbreviated “OHEL,” or “O Hell!” as he joked, to her great amusement).

Meanwhile Gresham began an affair with Rodriguez back in New York. Davidman returned home to a shattered marriage. Gresham attempted reconciliation (he was especially terrified of losing the boys), but Davidman had made up her mind about next steps: in the fall of 1953, she took David and Douglas and returned to England, this time for good.

Her first year was challenging: she did not have enough money, heat, food, or paying work, and had visa issues. Visits with Lewis sustained her, and he helped financially, paying for the boys’ boarding school tuition. They visited each other with increasing frequency, and she became his treasured companion, beloved friend, and trusted editor. The book he considered his greatest novel, Till We Have Faces (1956), was born of their creative collaboration. In March 1955 Joy spent a weekend at The Kilns, and they sat down with a bottle of whiskey and “kicked a few ideas around till one came to life.”

By the end of the next day, Lewis had written the first chapter; Davidman critiqued it and those that followed. The resulting tale blends themes and imagery from their parallel spiritual journeys (see pp. 49–52). George Sayer, in Jack, said she could “almost be called its joint author” and that she “stimulated and helped [Lewis] to such an extent that he began to feel that he could hardly write without her”—a “preparation for a complete and successful marriage.” Lewis dedicated the book to her.

Feasting on love

When Davidman told Lewis the Home Office might not renew her papers, Lewis, unable to bear the thought of her leaving England, agreed to a civil union in April 1956. But it took a diagnosis of her terminal cancer a few months later for him to recognize that philia had given way to eros. After doctors predicted months to live, they had a Christian marriage in her hospital room.

A miraculous remission gave them three blissful years from 1957 to 1960; they walked, talked, read, and even traveled to Ireland and Greece. Lewis wrote in A Grief Observed that they

feasted on love; every mode of it—solemn and merry, romantic and realistic, sometimes as dramatic as a thunderstorm, sometimes as comfortable and unemphatic as putting on your soft slippers. No cranny of heart or body remained unsatisfied.

Humbled by cancer, transformed by love and compassion from Lewis and others, Davidman softened into a better version of herself.

Joy Davidman Gresham Lewis died in Oxford in July 1960, at the age of 45; her ashes were installed in the Oxford Crematorium. But her story didn’t end there. In life Lewis’s British colleagues had received Davidman with mixed reviews; Warnie Lewis adored her, as did close friends June and Roger Lancelyn Green, among a handful of others, but many found her intolerable.

Anti-Semitism, anti-Americanism, and the 1950s stigma attached to divorce may have contributed. Reserved Brits didn’t warm to a brash New Yorker. Others were disgusted by behavior that was often rude, selfish, and manipulative. Some scholarly and fictional depictions have downplayed or omitted less endearing chapters of Davidman’s life—her immersion into Dianetics after converting to Christianity, or leaving David and Douglas, ages eight and six at the time, with her unstable husband for five months while she pursued Lewis in England.

But neither extreme does justice to the nuanced complexity of Davidman’s human condition. The “softening” she exhibited in her final years was sanctification, a process impossible to fully recognize without embracing the multiplicity of details—black, white, and shades of gray—that came before. CH

By Abigail Santamaria

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Abigail Santamaria is the author of Joy: Poet, Seeker, & the Woman Who Captivated C. S. Lewis and the cofounder of Biography by Design. She is currently writing a biography of Madeline L’Engle.Next articles

“At our level”

Lewis was a loving correspondent, godfather, and friend to the children in his life

Joe RickeQuestions for reflection: Jack at home

Questions to help you think more deeply about this issue.

the editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate