“At our level”

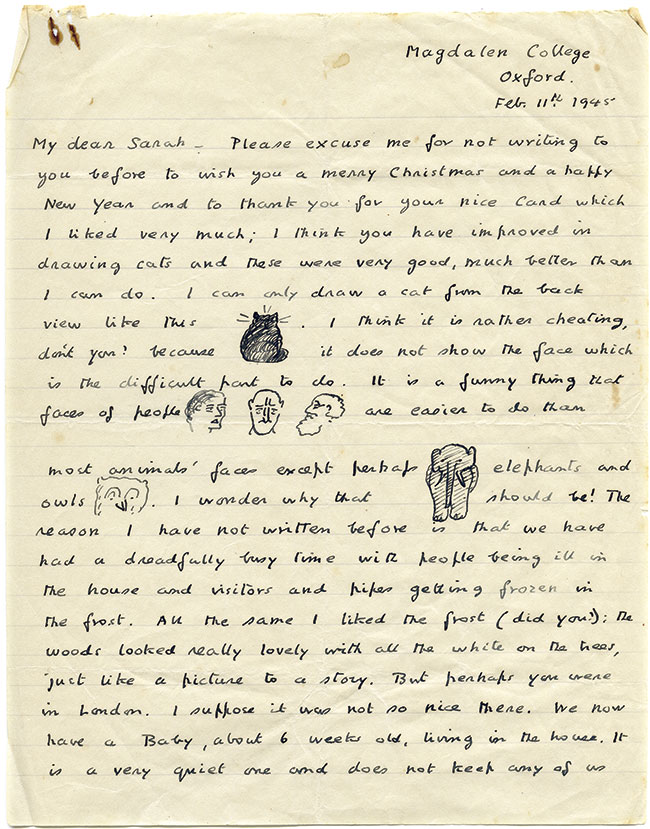

[Letter to Sarah Neylan. Used by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL / © C. S. Lewis Pte. Ltd. Reprinted by permission]

Many people experienced C. S. Lewis as intimidating, even downright scary. Just think of speakers who dared argue with Lewis at Socratic Club meetings in Oxford on cold winter’s nights in the 1940s. Or an Australian tutorial student with the gall to admit he did not like Matthew Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum (1853), at which Lewis announced, “The sword must settle it!,” forcing the student to fence with him until Lewis drew blood. Or another student whom Lewis chased out of a tutorial, yelling after him down the staircase, “If you think that way about Keats, you needn’t come back here again!”

Like a hippo

Yet, surprisingly, Lewis’s relationships with children were friendly, jovial, and even tender. One of Lewis’s four godchildren, Sarah Neylan Tisdall (1938–2017), remembered him as thoughtful, loving, and supportive.

Lewis attended her baptism, remembered her at Christmas, birthdays, and her confirmation, and related to her in childlike and whimsical ways. As a child Tisdall sent Lewis pictures of animals she had drawn. He sent back thoughtful comments on her drawings, his own fanciful animal drawings, and an illustrated true story (and poem) about his local rabbit friend. Tisdall eventually studied art at the prestigious Slade School in London and became an accomplished painter and muralist.

As Tisdall grew older, Lewis paid for her ballet lessons and prayed for her daily. Their lively correspondence covered the novels of Jane Austen and Rider Haggard, Tisdall’s pony, school, foreign languages, and the curious fact that Lewis liked to submerge in his tub like a hippo with only his nostrils above water! It was high praise indeed when he wrote to Tisdall’s parents, his former student Mary Neylan and her husband, Daniel, assuring them that Sarah was “old enough to talk to.”

Lewis also attended the baptism of another godchild, Laurence Harwood (1933–2020), son of Daphne and Cecil Harwood (see p. 1); he later wrote the parents that he hoped the baby’s laughing throughout was not a sign of trouble ahead. Harwood would characterize Lewis as a “regular and jovial” houseguest: “I remember still the excitement of his arrival, his presence, the laughter, and the bonhomie it created. Starting first thing in the morning with him emerging from our only bathroom, saying in his booming voice, BATHROOM FREE!”

Harwood rejected outright Lewis’s self-description as “not good with children.” In fact it was not unusual for Lewis to get on the floor with the five Harwood children and play “at our level, not in the patronizing way . . .” Throughout their relationship, “[Lewis] was able to pitch it at my level, whatever level I was.” While writing That Hideous Strength in 1944, Lewis wrote to the young Harwood: “I’m writing a story with a Bear in it and at present the Bear is going to get married in the last chapter. There are also Angels in it.” He also drew pictures—Magdalen College, corduroy pants, his rabbit friend (again!), and a self-portrait (eating venison). Later he sent puzzles, questions, and runes for Laurence to decode, discussed “the best kind of smells” (books and new shoes), and asked Harwood whether Lewis should read Oliver Twist or not.

When Daphne Harwood died of cancer, Lewis gave solace to both father and son. When failure at Oxford devastated his godson, Lewis not only comforted and advised him (Harwood said he “redeemed my belief in myself”), but acted on his behalf. Later, once Harwood had found his vocation, Lewis paid for three years of Royal Agricultural College. In a lovely irony, after Lewis had become a stepfather (see pp. 49–52), Harwood helped his stepson, Douglas Gresham, find a placement. In a touching final letter to his charge, Lewis wrote, “You’re more like a godfather (fairy type) than a godson.”

Escaping the blitz for The Kilns

During World War II, Lewis became a houseparent at the The Kilns, where girls evacuated from London could escape the Blitz. The first three arrived on September 2, 1939, as part of the initial wave in which over a million city dwellers were relocated. Over the course of the war, 11 young girls came to The Kilns.

As the appeal to take them in had been made primarily to mothers, the original idea was that Mrs. Moore and Maureen (see p. 35) would oversee the evacuees. But Maureen married in 1940, and Mrs. Moore often seemed uninterested. Lewis, by all accounts, threw himself into making the girls’ lives more bearable, showing genuine concern for them and providing opportunities for both learning and fun. They later testified that he built up their intellectual ability, helped them with their schoolwork, and introduced them to the larger Oxford world.

Lewis arranged to have male students from Oxford visit The Kilns on weekends to play tennis and swim, inviting the girls to join in. He took the girls on walks, smuggled them extra food at night, helped them raid the kitchen or listen to records in his study, and took them to the local pub for fish and chips. As many were Catholic, Lewis sometimes attended Mass with them.

The most lasting of these relationships was the friendship that developed between the Lewis brothers and June Flewett (b. 1927), a pretty, talented, and energetic girl who came to interview in 1942, and to stay in 1943, and all but refused to leave until January 1945.

Unlike the other evacuees, Flewett already knew of Lewis because she had read The Screwtape Letters (just published in 1942). Ironically she had no idea at first that her pipe-smoking host was the famous author. After making the connection, she felt terribly uncomfortable, worried that all her shortcomings must have been obvious to the insightful moralist. Lewis lampooned himself in a whimsical note, mock-chastising her heathen habit of throwing salt over her shoulder.

In fact, though, Flewett said later, “Lewis was the first person who made me believe I was an intelligent human being. The whole time I was there he built up my confidence in myself and my ability to think.” Lewis inscribed a copy of Screwtape to her with this poetic riddle: “Beauty and brains and virtue never dwell / Together in one place, the critics say. / Yet we have known a case / You must not ask her name / But seek it ‘twixt July and May.”

In 1945 Flewett left to attend the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, paid for by Lewis. She was at first hesitant, feeling she should stay to help with housekeeping at The Kilns (Moore was now elderly). Lewis wrote Flewett’s mother saying he was tempted to allow her to stay, but “I think she ought to go. From the point of view of her career she is wasting time by staying.” After she left he wrote, “I have never really felt anything like her unselfishness and patience and kindness and shall feel deeply in her debt as long as I live.”

“First gained a friend”

The Lewis brothers remained in touch with Flewett and saw her perform on multiple occasions. She became a successful actress under the stage name of Jill Raymond, married broadcasting personality Clement Freud (1924–2009, grandson of Sigmund Freud), and became Lady Freud. She continued to visit The Kilns and had, in fact, been planning to visit the day Lewis died.

Not good with children? Hardly. As a child Lewis had been rather lonely in terms of friendships. He had Warnie, books, and, eventually, Arthur Greeves (see pp. 24–26). Perhaps playing games “at our level” was part of the same impulse Lewis revealed in the Narnia books, in his delightful letters to children, and in sensitive essays like “How Not to Write for Children.” His incredible capacity for communicating with children reveals a deep desire, as Laurence Harwood remembered, “just to feel what it was like to be our age and to enjoy the things that we were enjoying.” Perhaps the beauty of one of Douglas Gresham’s oft-repeated sentences is more than rhetorical. Coming to The Kilns, uprooted and uncertain, Gresham testified that in Lewis he “first gained a friend and later a much-loved stepfather.” CH

By Joe Ricke

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Joe Ricke is the director of the InklingFolk Fellowship.Next articles

Questions for reflection: Jack at home

Questions to help you think more deeply about this issue.

the editorsJack at home: recommended resources

With scores of books by and about C. S. Lewis—where to begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center.

the editors"Something profound had touched my mind and heart”

Some of Lewis’s scholarly colleagues and those who carried on his legacy

Jennifer A. BoardmanSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate