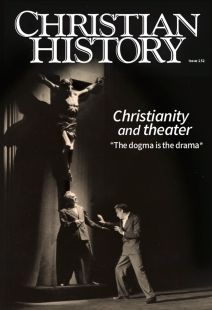

Wizards’ duels and modernist mayhem

[ABOVE: George William Russell and William Butler Yeats, Theosophical Mural at 3 Ely Place, Dublin, Late 1880s—Dorje de Burgh / Public domain, Wikimedia]

One day in 1900, William Butler Yeats kicked Aleister Crowley down a flight of stairs. This surprising “de-escalation” occurred after Crowley (1875–1947), a notorious practioner of black magic, showed up wearing full Scottish regalia, complete with kilt and dagger, and sporting a mask of Osiris. In this way, he tried to take possession of the temple of a secret society. The great poet Yeats (1865–1939), who claimed to be guarding the sacred space physically and spiritually, reportedly engaged him in a wizard’s duel on the astral plane. On the terrestrial plane, Crowley picked himself up and dusted himself off, only to be fined five pounds for breaking and entering.

What in the world (this world or any other) such a story has to do with Christianity and theater in the modern era is an excellent question. The answer is a little complicated, entangled with several interrelated religious movements in roughly the first half of the twentieth century, starring an overlapping cast of characters.

MODERNITY AND MYTH

Starting in the 1890s, what we might call mainstream modernism began stealing the spotlight of most major theaters around Europe. Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906) dominated the scene with his dark realism, setting the standards for those who followed. Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879) is a good example: its heroine is a wealthy but ordinary young mother, neglected and controlled by her husband; the action follows her growing self-awareness and attempts to establish independent personhood. Such “naturalism” in plays by August Strindberg (1849–1912), George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956), and others dominated the theater world, exploring psychologically complex characters in domestic conditions.

Christianity rarely featured in these plays, at least not positively. The same was true for other influential European authors. For example, Samuel Beckett’s (1906–1989) famous Waiting for Godot (1953) has been often interpreted as a dramatization of God’s absence, and Jean-Paul Sartre’s (1905–1980) No Exit (1944) infamously suggests that “Hell is other people.”

In response to the disasters of the twentieth century, these playwrights and their American counterparts frequently staged plays featuring insanity, substance abuse, bodily horrors, murder, sexual violence, suicide, and utterly absurdist chaos. Such despair would only deepen when World War II began and later, after the concentration camps were discovered.

However, this modernist mayhem was not all one could find at the theater: myth and enchantment also appeared. In Dublin the Irish Literary Revival produced dramas steeped in Celtic folklore and ceremonial magic. Some also reflected their Roman Catholic milieu, and even the occultist Yeats himself wrote two passion plays: Calvary (1921) and The Resurrection (1934). They are weird and unorthodox, combining the Crucifixion with a pagan festival, but they do affirm the Incarnation.

But a brilliant point of contact between these darlings of modernist playwriting and robust public Christianity was the noisy, bellicose, affectionate friendship between Shaw and G. K. Chesterton. They knew each other for decades and teased and argued endlessly. They staged public debates over economics, politics, religion, writing, and personal appearance. Reportedly they once opened a debate with the following exchange:

Chesterton: “I see there has been a famine in the land.”

Shaw: “And I see the cause of it. If I were as fat as you, I would hang myself.”

Chesterton: “If I were to hang myself, I would use you for the rope.”

One point of serious conversation between them was the relative importance of drama. Shaw chose plays as his main genre, and he cajoled Chesterton to do the same. Finally Chesterton wrote Magic in 1913. While it can hardly be what Shaw was hoping for—it is supernatural, spiritual, and more twilit than Shaw’s satirical comedies or hardy political plays—Shaw stood up for his friend and reviewed it positively. Whether Shaw liked it or not, Chesterton’s one foray onto the stage contributed to the reenchantment of a jaded culture.

QUIRKY NATIVITIES

Chesterton was not alone. Indeed so many Christian plays were written and performed in England in the first half of the twentieth century that we can identify something that George R. Kernodle (1907–1988), in 1940, called “England’s Religious-Drama Movement.” While he was talking specifically about the 1930s, religious drama moved through England (and Europe and America) over and over throughout the modern era. It wasn’t insulated from the mainstream, either. Indeed two playwrights provided strong, enduring links between modernist theater and the church: T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden (1907–1973).

Eliot’s conversion to Anglicanism in 1927 was widely publicized: praised by some, vilified by others. There is no question it benefited his drama. His previous works for the stage were few and fragmentary; after he came to faith, he wrote six successful plays. The magisterial Murder in the Cathedral was the most celebrated. It was commissioned for the 1935 Canterbury Festival—an important center of ecclesiastical drama of the highest quality (see p. 31).

The Canterbury Festival was the ingenious idea of actor/director E. Martin Browne (1900–1980). It ran from 1928 until 1948 (with a couple of years off during the Second World War, when Canterbury itself was bombed and sustained some damage), then restarted and is still going in 2024. During its first two decades, the festival commissioned several preeminent playwrights to write dramas that connected to the locale and embodied elements of Christian history on the stage.

Results included a quirky Nativity story, inspiring martyrdoms, demonic temptations, magi, artists, mystical figures, and music. Most of them were poetic dramas, written in meter. They were arguably the most important pieces in the larger “Verse Drama Revival” going on at the time. They blended medieval mystery, morality, and miracle plays with modernist experimentation and a new approach to traditional metered poetry for twentieth-century ears. For instance, Dorothy L. Sayers’s The Devil to Pay (1939) married these elements in a retelling of the legend of Faustus as a “serious comedy.”

One author commissioned for a Canterbury play was also a member of another small group of writers who must be mentioned in any survey of Christian literature in English in the twentieth century: the Inklings (see CH #113). This group consisted mostly of Oxford graduates and faculty, the majority of whom were writers by vocation or avocation, and all of whom were Christians of one sort or another. They met weekly or biweekly from the late 1920s until 1945 to share drinks, talk, and drafts of works in progress.

While they produced few dramas overall, one of them was an avid playwright: Charles Williams (1886–1945). He was also the central point of overlap among mainstream modernism, the Canterbury Festival, and the Inklings. Williams was a Londoner, was not a college graduate, and was only in Oxford from 1939 to 1945 as a result of evacuation from London during the Blitz. While we primarily remember him as a novelist or poet, during his lifetime he was better known for his plays.

In addition to Williams’s 1935 Canterbury commission, he worked with several other theatrical companies and directors to write scripts specifically with their actors and venues in mind. During the Second World War, for example, he roomed in the house of the extremely talented young director Ruth Spalding (1913–2009), who founded and ran the Oxford Pilgrim Players. This itinerant group traveled around Oxfordshire, performing in churches, schools, air-raid shelters, or wherever they could provide some artistic nourishment to frightened and exhausted audiences. For Spalding, Williams wrote his most “intelligible” plays, as C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) called them: The House by the Stable (1939) and Grab & Grace (1941). While Williams’s dramas range from the barely comprehensible to the celestially enlightening, they are all beautiful, inspiring, and radiant.

DRAMATIC INKLINGS

The rest of the Inklings were hardly involved in public drama. Lewis tried to write for the stage a few times, but never succeeded. J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973) wrote only one play: The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son (1953), a continuation of the Old English poem The Battle of Maldon. Surprisingly performable and moving, it has only two characters and is in verse. It was actually broadcast on the BBC in 1954.

Owen Barfield (1898–1997) wrote one play entitled Orpheus (1938), some pieces of “eurythmy,” and some Anthroposophical mystery plays. Eurythmy is a kind of choreographed movement performed over a textual narration, and the Anthroposophical Society is a quasi-religious school of thought founded by esotericist Rudolf Steiner (1861–1925). Barfield’s dramatic works, then, were written for a specific philosophical-spiritual context, not for general performance.

But there were two exceptions. The youngest Inkling, John Wain (1925–1994), wrote four plays. Johnson Is Leaving (1973) is a monologue depicting the great Samuel Johnson’s last days, while Frank (1984) imagines the life of Johnson’s Jamaican servant, Frank Barber. Wain often worked with others: jazz composer Michael Garrick wrote music for Harry in the Night (1975), and Hungarian scientist Laszlo Solymar coauthored radio plays entitled Three Scientists of the Ancient World: Anaxagoras, Archimedes, Hypatia. They were broadcast on the BBC in 1991.

The most important Inkling, by far, when it came to the stage, was Nevill Coghill (1899–1980). He was an excellent director, founder of the Experimental Theatre Club in Oxford, coauthor of at least one play, an integral part of theatrical life at Oxford University, a notable interpreter of Shakespeare, and editor in various capacities for Eliot’s plays. Perhaps most memorably he taught Auden and directed a young Richard Burton, both on stage and then later on screen with Elizabeth Taylor. He also made a musical adaptation of The Canterbury Tales that became a hit on Broadway and later made it to television.

THE OCCULT AND THE ESOTERIC

Thanks to Coghill, Wain, and Williams, the Inklings had an extraordinary influence on English drama. And thanks to Williams, the Inklings (in a tangential way) were connected not only to modern Christian theater but also to the theater of the modern occult revival. From 1888 until 1945, secret societies flourished in Europe and America. They came on the heels of spiritualism, which nurtured a couple of crackpots claiming to take dictation from dead dramatists and publishing their posthumous plays! The more serious groups attracted many notable members, including several brilliant authors. Under the influence of the ceremonial magic they practiced, such playwrights produced an astonishing number of dramas both didactic and invocatory.

Oddly, the occult movements overlapped with some Christian dramatic movements. Williams was a high-ranking leader in a secret society while also calling himself a Christian. A well-known theological author, he packed his plays with doctrines from both traditions, seeing the deepest union between the two. Other writers also were simultaneously members of Christian churches, magical secret societies, and modernist literary movements.

It should be clear, now, what a story about Yeats and Crowley in a wizards’ duel has to do with Christianity and theater in the modern era. Among many of these writers, Christian religion, other spiritualities, magical secret societies, and drama were all interrelated and could not be disentangled. None of their stories can be told without bringing in the others. Christian theater has, throughout its history and to varying degrees, been a kissing cousin with magic and myth (see pp. 22–24). In the modern period, they were allies in the quest for reenchantment.

Even though Williams was a member of a secret society distantly related to Aleister Crowley’s personal religion, and even though he saw no contradiction between Christianity and hermeticism, it seems likely that if Williams had met Crowley, he too would have kicked him down the stairs. CH

By Sørina Higgins

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Sørina Higgins is an editor, writer, and scholar of British modernist literature.Next articles

From Aztlán with love

Mexican American religious and ethnic identity played out on the stage

Daniel F. FloresSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate