From Aztlán with love

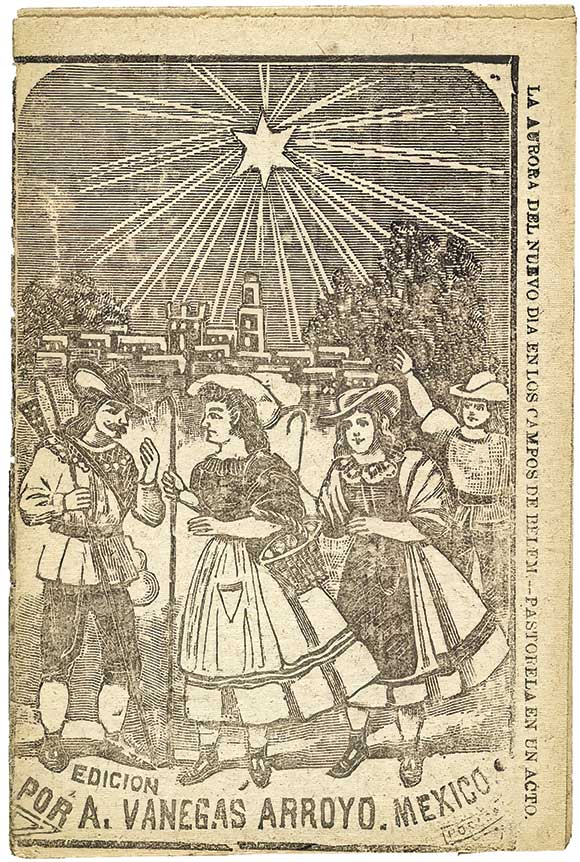

[ABOVE: José Guadalupe Posada, The dawn of a new day in the fields of Bethlehem, one-act pastorela, chapbook cover, Mexico City, 1890 and 1913—Public domain, Library of Congress]

Ladies and gentlemen

The play you are about to see is a construct of fantasy.

The Pachuco Style was an act in Life and his language a new creation.

His will to be was an awesome force eluding all documentation. . . .

A mystical, quizzical, frightening being precursor of revolution

Or a piteous, hideous heroic joke

Deserving of absolution?—Zoot Suit

The play Zoot Suit (1979), by Chicano (Mexican American) playwright Luis Valdez (b. 1940), is based on the 1942 Sleepy Lagoon murder case and the Zoot Suit Riots. Henry Reyna, the main character, is accused of murder along with members of the 38th Street gang of Los Angeles. El Pachuco, unseen and unheard by the other characters, is Henry’s wise-cracking, zoot-suit-wearing alter ego. El Pachuco taunts and teases Henry, trying to provoke him to act on his antisocial thoughts.

Most Americans may never encounter the plays of Valdez outside of university drama or Chicano history courses. Valdez was the founder of Teatro Campesino (Farmworker’s Theater), the drama company associated with activists Cesar Chavez (1927–1993) and Dolores Huerta (b. 1930) of the United Farm Workers. Teatro’s gritty, irreverent style was used in skits presented on picket lines and fields to encourage strikers and discourage the “scabs” hired to replace them.

FAITH IN AZTLÁN

Teatro Campesino leaped onto the national stage when Zoot Suit played on Broadway on March 25, 1979. Released in theaters in August of 1981, it was nominated for a Golden Globe Best Motion Picture (Musical or Comedy) in 1982. It won the 1983 Critics Award at the Festival du Policier de Cognac, and it also launched the career of Edward James Olmos (b. 1947) who played

El Pachuco.

Teatro Campesino introduced its star-studded cinematic version of La Pastorela: The Shepherd’s Tale on December 23, 1991, on PBS Great Performances. For the first time, English-dominant audiences were granted front-seat access to La Pastorela, one of the most cherished stories of Aztlán. Aztlán is Mexico’s mythical world of magical realism where Mexican religion and culture thrive.

The play is set in a California migrant farmworker camp on La Nochebuena, Christmas Eve. Teenager Gila Diaz, played by Karla Montana, suffers a head injury while watching a presentation of La Pastorela during Midnight Mass.

In a dream sequence reminiscent of Dorothy’s transport to Oz, Diaz awakens at a rural campsite of poor shepherds minding their sheep. The archangel San Miguel (Saint Michael), played in the movie by Linda Ronstadt, appears in the sky singing an announcement of the birth of the Messiah. Filled with faith the ablest of the camp embark on a pilgrimage where they must face trials by Luzbel (Lucifer), played by Roberto Beltran; Satanas, played by Paul Rodriguez; and the trickster El Cosmico, played by Cheech Marin. The shepherds persevere, finally reaching Belen (Bethlehem) while dancing and singing songs of faith. San Miguel sends Luzbel and his minions back to hell as they wail in agony. Diaz is injured again but awakens safely at home surrounded by the actors who populated her dream.

La Pastorela and Zoot Suit both draw their stories from the challenges of social location familiar to Mexican Americans. They carry forward a message of hope against the harsh realities of oppression and poverty.

SACRAMENTAL DRAMA

Though seemingly quite modern, Valdez was drawing on old traditions unique to his Mexican American culture. Both in Valdez’s time and generations before, a Roman Catholic and Indigenous identity played out on the stage.

In Mexico the early modern thinker Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695) stood out for her brilliant literary works (see p. 45). She is not as well known as Valdez in the English-speaking world. However, this former lady-in-waiting who ended up a Hieronymite nun is held in high esteem as Mexico’s first theologian and celebrated poet—and playwright.

Sor Juana wrote her plays in the style of the auto sacramentales of Spain. Auto sacramentales were religious mystery plays that used allegory to teach theological concepts of Roman Catholicism. In Mexico and other parts of New Spain, they were a means of missionizing Indigenous peoples living in colonial lands. Sor Juana’s most celebrated work is a mystery play entitled The Divine Narcissus (1689). The players include Occident, America, Zeal, Religion, Music, and Soldiers. At the end of scene 4, Religion, speaking to Occident, explains the reason for using visuals to explain the concepts of faith:

RELIGION: All right, let us begin. First, you must know it is a metaphor, an idea dressed in the colors of rhetoric and visible therefore to your eyes, as I shall reveal to you; for I well know you are more inclined to favor objects that can be seen over the words that faith can tell you; and so, my friends, instead of ears you need to use your eyes to learn the teaching that faith will show you.

OCCIDENT: True: I would rather see it than have you recount it to me.

Sor Juana’s works are not just didactic, but engaging, witty, and deep with symbolic meanings that capture the intended audience. Indeed the use of religious imagery in plays has a long history in Mexico predating Spanish colonial times. Later Mexican Indigenous tribes shaped their dramas around the cult of La Virgen de Guadalupe, a dark-skinned apparition of the Virgin Mary, known in English as Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Known affectionately as La Morenita, her cult replaced that of the Aztec fertility goddess Tonantzin. Where the Roman Church repeatedly failed in its efforts to missionize Mexico’s Indigenous tribes, sight, as Occident had noted, was far more effective.

According to tradition, La Morenita appeared to Juan Diego, an Indigenous man, on December 9, 1531 (see CH #130). News of this event triggered mass conversions among Indigenous tribes and unified them as Mexicans. The lasting importance of this event was highlighted by Juan Diego’s beatification on May 6, 1990, and canonization on July 31, 2002, by Pope John Paul II.

Today matachines, traditional carnivalesque sword dancers, keep La Morenita’s story alive with their dances and dramatic storytelling. They combine the European auto sacramentales with Aztec Indigenous tradition to preserve and promote their Mexican form of Catholicism.

Dancers wear feather headdresses and embroidered skirts with rattles and bells called nagüillas. They also wear vests adorned with rattles, jingle bells, and fringes. They carry arcos, nonfunctional bows and arrows, and sonajas, or rattles. Matachines dance to beating drums and accordions in simple to advanced choreography.

Dances may feature iconic characters such as La Malinche, a multilingual Indigenous woman blamed for betraying her people to the Spanish conquistadores. Actors may also portray tricksters who wear the mask of a demon, or diablo, and carry weapons such as whips or clubs. Matachines dance anywhere, but one is most likely to see them perform at Roman Catholic churches on May 3 for the feast of the Holy Cross or on December 12 to honor La Morenita.

SHOW, DON’T TELL

These forms of Mexican American religious dramas serve to preserve culture by teaching Roman Catholic thought mixed with Indigenous cosmology to new generations. While the plays differ in their religious content and messaging, all share the hope that comes from the Mexican concept of familia, which reflects the Roman Catholic esteem for the Holy Family. Aztlán’s values may be difficult to appreciate outside of the Mexican American community. Once again some may agree with Sor Juana’s character, Occident, that they would rather see a good story than have it recounted to them. CH

By Daniel F. Flores

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Daniel F. Flores is senior librarian at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and director of the Goddard Library.Next articles

“Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”

In liturgical traditions, such as the Orthodox Church, believers who participate in Holy Week’s drama enter into Christ’s passion.

Cyril Gary JenkinsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate