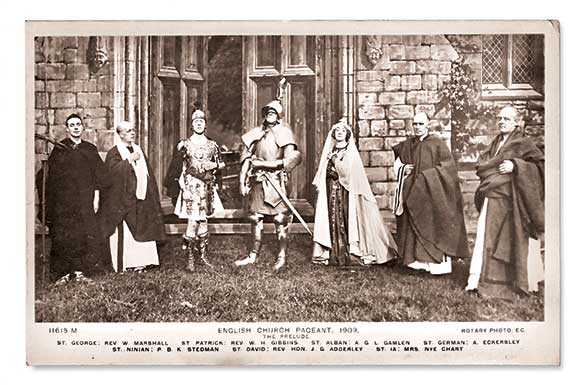

The pageant

[Rotary Photo, E. C., English Church Pageant, 1909, post card—Christian History Institute Archives]

The word “pageant” might conjure the idea of beauty competitions or children’s Christmas and Easter plays today, but in twentieth-century Britain, the pageant was something else. Although largely forgotten now, pageants were everywhere. These massive theatrical and social events typically involved casts up to 15,000 players. Popular pageants attracted audiences of over 100,000 people across a weekend or two, bringing the history of a village or city to the public.

The genre was loosely influenced by earlier types of civic and religious ceremonies, such as medieval mystery or passion plays (see pp. 12–16) and Lord Mayor Shows. Still observed today, the Lord Mayor Show is a procession honoring each Lord Mayor of the City of London (separate from the mayor of London). As part of this procession in the early modern period, pageants were professionally staged along the route for the new Lord Mayor. Twentieth-century pageants, however, relied upon volunteer casts, largely made up of locals. A strong community spirit was crucial, most evident when audience and performers sang together the national anthem and popular songs like “Jerusalem” or the hymn “O God, Our Help in Ages Past” at the pageant’s conclusion.

COMMUNITY THEATER

Institutionalized religion and its close relationship with the British monarchy ensured the depiction of Christian spaces, figures, and themes. Cathedrals and churches, standing or ruined, often served as backdrops for outdoor pageants. Bishops, monks, nuns, and even Chaucer’s pilgrims were recurring characters alongside royalty, nobles, peasants, and knights. Pilgrimage, consecration, and conversion became conventional subjects for scenes that depicted the invasions of the Romans, Danes, and Saxons. These themes and characters featured most strikingly in The Rock (1934), an indoor pageant-play written by T. S. Eliot (1888–1965). The action staged the history of church-building in London; its title character was inspired by the apostle Peter.

An earlier pageant, the English Church Pageant (1909), had presented an entire history of English Christianity, drawing upon the talents of clergyman Percy Dearmer (1867–1936), who contributed some of the writing. Composer Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872–1958) served as musical consultant for the production, staged at the bishop of London’s Fulham Palace grounds. Among the 4,200 performers was G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936), who commented, “The mass of the common people cannot afford to see the Pageant; so they are obliged to put up with the inferior function of acting in it. I myself got in with the rabble in this way.” Chesterton performed as Samuel Johnson and later wrote a comical ghost-slash-mystery short story, “The Mystery of the Pageant” (1909), about his experience.

CONTINUING THE TRADITION

Pageants often raised money for a local church. In E. M. Forster’s (1879–1970) Pageant of Abinger (1934), a woodman compares the fleeting passage of human history to the endurance of trees and forests; Forster thematically connected trees with the need for funds to repair the local church’s wooden roof beams.

Perhaps the most lasting contribution of pageants came through some of the works commissioned by Bishop George Bell’s (1883–1958) Canterbury Festival. These included Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral (1935), Charles Williams’s (1886–1945) Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury (1936), and Dorothy L. Sayers’s (1893–1957) The Zeal of Thy House (1937). These writers had engaged with pageants before. Sayers, for example, had performed in a pageant as a girl. Eliot used the same choral techniques he had developed in The Rock for other works. Williams wrote the pageant-play Judgement at Chelmsford (1939), which tells “not only of the history of the [Chelmsford] diocese, but of the movement of the soul of man in its journey from the things of this world to the heavenly city of Almighty God.”

While this cultural phenomenon captivated the British imagination at the time, the pageant’s popularity has waned in the twenty-first century. Still, its extraordinary production power left its mark. In June 2022 a large pageant was staged for Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee in London. That same year Axbridge hosted a massive pageant in its town square, where an enactment occurs every 10 years. In both, the church and religious themes still loom large.

By Parker T. Gordon

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Parker T. Gordon is a scholar of twentieth-century literature and musicNext articles

Wizards’ duels and modernist mayhem

Magic, myth, and Christ in twentieth-century theater

Sørina HigginsFrom Aztlán with love

Mexican American religious and ethnic identity played out on the stage

Daniel F. FloresSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate