Custom-breakers

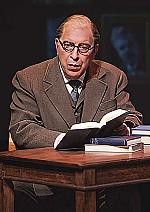

[ABOVE: William Larkin, Probably Elizabeth Cary, née Tanfield, oil on canvas, c. 1614 to 1618—Suffolk Collection, Kenwood House / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Although women have been making theater for centuries, they have been excluded from this public, collaborative art in many societies, from ancient Greece onward. The relationship between Christianity and theater has not always been an easy one. Yet long before the first professional women playwrights entered history, Christian women were making theater—writing plays, dialogues, and scenarios. Some also performed, directed, costumed, sang, and danced. Many of the women who we know did this were nuns.

HROTSVITHA (c. 935–c. 1000)

Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim is usually identified as the first recorded woman playwright. She was a well-educated Benedictine secular canoness who wrote several original plays. Hrotsvitha lived in a privileged environment where she had access to libraries and where classical learning was respected. She was also surrounded by women who performed daily services, singing, memorizing, and repeating liturgy.

Today Hrotsvitha’s plays seem an odd mixture. They deal with virgin martyrs and prostitutes, battles and torture, tragedy and farce. In Dulcitius (10th c.), a play loosely based on a true story, the pagan villain Governor Dulcitius tries to control, punish, and then seduce three Christian virgins. Bizarrely, Dulcitius gets into a farcical fight with brooms, saucepans and other kitchen utensils, and becomes covered with soot. He then has the poor virgins martyred. In another play, Abraham, a young woman, Mary, becomes a prostitute and enjoys her life. Later she repents and retreats to live in penitence in a cell. A courtesan named Thais is at the center of Hrotsvitha’s Paphnutius. Thais reveals that she is a Christian, and she is brought to repentance by a holy man who disguises himself as a customer.

Most of Hrotsvitha’s plays are named after her male characters, but the action always focuses on women and the challenges they face. Were the plays performed? We don’t know. Although Dulcitius’s battle with the pots and pans begs to be staged, Hrotsvitha’s scripts may have been read aloud rather than acted out. But convent life involved plenty of ceremonial and musical performance, and it is perfectly possible the nuns could have staged her dramas. One reason Hrotsvitha’s plays were preserved is that convent life valued and encouraged learning and the ability to speak well.

HILDEGARD OF BINGEN (1098–1179)

The early woman Christian playwright best known today, abbess and Catholic saint Hildegard of Bingen, was also a composer, visionary, theologian, preacher, natural scientist, herbal healer, and enthusiastic letter writer. She was a political power broker and, like Hrotsvitha, wrote in the international European language, Latin. But she took a very different approach to dramatic characterization. Hildegard’s play, the Ordo Virtutum, or Order of the Virtues (c. 1151), is a musical and liturgical drama that shows 16 female Virtues struggling against the Devil for the possession of a female soul, Anima. Although the Devil entices Anima into dallying with worldly pleasures, she later repents, returning somewhat battered to the Virtues. After joining together, Anima and the Virtues defeat the Devil.

In creating the Ordo, Hildegard thought very theatrically in terms of space, pacing, and dramatic conflict, anticipating the development of medieval morality plays by about a century. The play was probably staged when Hildegard moved with her 20 nuns into a convent she had founded at Rupertsberg on the Rhine. This relocation was made in defiance of her abbot who opposed the move.

ANONYMOUS

It is possible but unlikely that women may have written some of the medieval morality plays and mystery cycle plays that today have to be ascribed to “Anon.” The mystery plays, inspired by stories from the Bible, were produced for the feast of Corpus Christi by the trade guilds (see pp. 12–16), but women would have contributed to and supported these performances even if it was backstage helping to create costumes, doing the laundry, and performing other essential tasks.

KATHERINE OF SUTTON (d. 1376)

Another pioneering nun playwright, Katherine of Sutton was probably England’s first woman playwright, as well as the abbess of Barking. A politically powerful baroness, Katherine staged Easter plays at her abbey, dramaturging (writing and adapting plays in Latin) for the specific performance conditions there. Her nuns would have performed the roles of the male characters, which is startling because it was not until 1660 that women could legally appear on an English stage performing as female characters, let alone as men. In Barking, the enclosed, relatively safe space of the convent allowed women the freedom to express their faith through theatrical performance.

MARGUERITE OF NAVARRE (1492–1549)

While some puritanical Protestants were antitheatrical, Catholic Marguerite of Navarre used plays to encourage reform within her church. Marguerite, sister of Francis I, king of France, was a powerful, well-educated member of the French ruling class. She upset many traditionalists with her reforming and proselyting activities. Marguerite is best known as a writer of short stories, assembled in the often-bawdy Heptameron, but she wrote prolifically in many genres. Her plays sometimes mocked those in authority in the Catholic Church, especially authorities who were corrupt, lazy, and poorly educated. Marguerite also produced translations, which was seen to be less presumptuous for women than authoring their own writing.

LADY JANE LUMLEY (1537–1578)

The first woman known to have created a play in the English language, Lady Jane Lumley also worked with translation, producing an English version of Euripides’s Iphigenia at Aulis. But Lumley shifted, even adapted, Euripides’s text, cutting back on the choruses as she turned Greek verse into English prose. The focus is on the violent and ritual sacrifice of the young woman Iphigenia so that her father, King Agamemnon, can go and fight his war in Troy.

The story connects with the realities of Christian life in England in 1554, the time Lumley was writing. Lumley’s first cousin was Lady Jane Grey (1537–1554), and Lumley’s father, Henry Fitzalan (1512–1580), Earl of Arundel, Lady Jane Grey’s uncle, had initially supported his niece as the successor to King Edward VI.

Jane Grey became the Protestant queen of England for just nine days. But Fitzalan quickly abandoned his niece and switched sides to support the Catholic Queen Mary, who then executed Lady Jane Grey (one of the reasons being her refusal to convert). Shortly after the execution of her cousin, Jane Lumley produced Iphigenia in Aulis, which asks the reader to contemplate the sacrificial slaughter of a young woman to further the ambitions of her family. Evidence suggests that Henry Fitzalan was intended to be the first reader of Lumley’s play.

ELIZABETH TANFIELD CARY (1585–1639)

The Protestant and Catholic divide also affected the life of Elizabeth Tanfield Cary. Cary wrote her play The Tragedy of Mariam, Fair Queen of Jewry around 1605. She is remarkable for, in 1613, being the first woman known to have published an original drama in English. Cary only used her initials, E. C., on the title page because by publishing her work and putting it in the public domain, Cary risked damage to her reputation. In this period theater-making was seen as low-status work. Actors, or players, even those as talented as Shakespeare, were associated in English law with rogues and vagabonds.

In Mariam Cary presents the second wife of Herod the Great, Mariam, as a Christ-like martyr, who chooses integrity and principles over life, refusing to compromise even when she knows this will result in her death. Meanwhile Cary’s villain, Herod’s transgressive sister, Salome, defies convention, is utterly shameless and, in performance, very hard to resist. Salome schemes to bring about the downfall of the virtuous but theatrically less interesting Mariam. Salome refuses to accept the constraints society sought to impose on her and demands, “Why should such privilege to man be given?” She decides to become a “custom-breaker” and the first Jewish woman to secure a divorce.

The play focuses on two women struggling within marriage, with one accepting oppression and the other scheming her way toward divorce. Later on life began to imitate art. Cary had married Sir Henry Cary in 1602, but the marriage became troubled, and Cary, like Salome, became a rebel.

She converted to Catholicism when her husband was the Protestant Lord Deputy of Ireland and in charge of keeping the predominantly Catholic population under control. Cary defied her husband and King Charles I and sought the protection of his Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria. The great-granddaughter of Marguerite of Navarre, Queen Henrietta Maria also also shocked many in England because of her love of participating in court theatricals.

We know much about Elizabeth Cary’s life because one of her daughters, a nun in the Benedictine convent at Cambrai, wrote a manuscript account of it. This biography does not mention that Cary wrote plays—she probably wrote two, but one play, set in Sicily, is lost—but the biography does state that Cary loved seeing plays performed. It also narrates how Cary arranged for six of her children to be kidnapped so that they could receive a Catholic rather than a Protestant upbringing. Four of Cary’s daughters chose to live their lives in convents in France, while Cary in later life lived in extreme poverty as her husband would not pay her any maintenance.

SOR JUANA INÉS DE LA CRUZ (1648–1695)

Theater-making by women in convent settings garnered criticism when subjects moved beyond safe matters like liturgical drama or virgin martyrs in peril. Mexico’s Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, a Spanish Criolla (a Hispanic American of full Spanish descent), hosted literary salons, was friends with the vice-regal family, and wrote a defense in favor of women’s education. Sor Juana became a controversial figure when she scripted plays that dealt with worldly romance. Toward the end of her life, she may have destroyed much of her work, possibly as an act of penitence. On the other hand, many of her writings may have been destroyed after Sor Juana was compelled to give up her huge library.

SOR MARCELA DE SAN FÉLIX (1605–1688)

A similar fate lay in store for the writings, including plays, produced by another nun, Sor Marcela de San Félix. A daughter of famous Spanish playwright Lope de Vega (1562–1635) and actress Micaela de Luján (1570–1614), Sor Marcela’s dramatic texts were mostly destroyed on the advice of her disapproving confessor.

DOROTHY L. SAYERS (1893–1957)

As professional women playwrights began to gain a foothold in the theater, their Christian identity, experience, and imagination tended to move into the background. The commercial theaters rarely staged overtly Christian material and, in England, censorship laws severely restricted what could be staged. Until the 1920s even church Nativity plays were controversial. All representations of the Holy Family on stage, even the baby Jesus, were banned. In 1941 a furor erupted when respected crime novelist, playwright, and critic Dorothy L. Sayers was commissioned to write a 12-part radio play series, The Man Born to Be King, on the life of Jesus.

Sayers wrote the plays in a realistic style, using colloquial language. They were scheduled to be broadcast for the Sunday Children’s Hour. Despite Britain being in the midst of the Second World War, people found time to protest Sayers’s plays and condemn her work before they had any idea what she had written. Later the plays of The Man Born to Be King were judged to be among Sayers’s best works.

THEATER MAKERS

Today it is commonplace for churches, schools, and youth clubs to stage Nativity plays, passion plays, and Bible narratives. Many women who do not see themselves primarily as theater makers are adapting, rewriting, and reshaping plays and dialogues. They are designing sets and costumes, composing and playing music, teaching dance, and providing refreshments. They may not be star names like Hildegard of Bingen, but long may their theater-making continue. CH

By Elizabeth Schafer

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Elizabeth Schafer is professor of drama and theatre studies at Royal Holloway, University of London.Next articles

“Were you there when they crucified my Lord?”

In liturgical traditions, such as the Orthodox Church, believers who participate in Holy Week’s drama enter into Christ’s passion.

Cyril Gary JenkinsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate