Fuel on a demonic fire

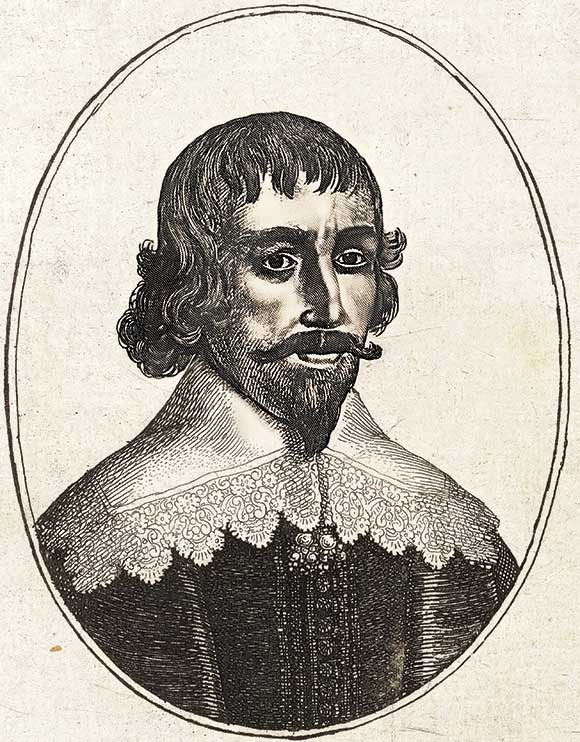

[ABOVE Wenceslaus Hollar, William Prynne, engraving, 17th Century—Public domain, Wikimedia]

That all popular, and common Stage-Plays, whether Comical, Tragical, Satirical, Mimical, or mixed of either . . . are such sinful, hurtful, and pernicious Recreations, as are altogether unseemly, and unlawful unto Christians: I shall first of all evidence, and prove it.—William Prynne, Histriomastix, The Players’ Scourge, or Actors’ Tragedy (1633)

In all the Churches those ministers most distinguished for piety . . . are most opposed to the Theater; while those notoriously indolent, luxurious, and tolerant to worldliness, with few exceptions, furnish ministerial apologists for the Theater.—James Buckley, Christians and the Theater (1876)

Almost as soon as there were Christians, some of them opposed the theater (see pp. 6–10). The Apostolic Tradition, a document of church order from around the early 200s, lists actors as those who must give up their profession before seeking baptism—alongside pimps, prostitutes, idol makers, those who take part in gladiatorial games, astrologers, and soldiers.

Likewise, pagan Romans, though many patronized plays, had a low opinion of actors, who were largely foreigners or the enslaved. Pagans also associated forms of theater with prostitution and general sexual immorality. To this moral critique, Christians added theological ones: the theater for them was associated with idolatry and with unreality.

These three issues, raised by early church thinkers like Tertullian (p. 11), remain surprisingly consistent down through the centuries whenever Christians critiqued theatrical endeavors—from Roman ludi scaenici (public theater festivals) and traveling acting troupes, to the Puritan closure of English theaters in the seventeenth century, to various protests as part of Victorian movements for public morality.

“FROTHY, VAINE, AND FRIVOLOUS”

The critique of immorality usually included both onstage immoral acts and the immorality of actors in their personal lives. Tertullian condemned “that immodesty of gesture and attire which so specially and peculiarly characterizes the stage” and accused theaters of bringing cross-dressing men and prostitutes on stage. William Prynne (1600–1669), Puritan author of one of the most famous antitheatrical treatises, Histriomastix (1632), argued:

If we survey the style, or subject matter of all our popular Interludes; we shall discover them to be either Scurrilous, Amorous, and Obscene: or Barbarous, Bloody, and Tyrannical: or Heathenish, and Prophane: or Fabulous, and Fictitious: or Impious, and Blasphemous: or Satirical, and Invective: or at the best but Frothy, Vaine, and Frivolous.

Furthermore, he continued:

as Stage plays are sinful, and utterly unlawful unto Christians in regard of their style and subject matter, so likewise are they in respect both of their Actors and Spectators.

Histriomastix came to the attention of King Charles I (1600–1649) because of perceived treasonous passages; Prynne was sentenced to life imprisonment (later cut short in 1640 by the Long Parliament that opposed Charles I), a fine, and having his book burned in front of him.

The Long Parliament prevented the staging of plays in 1642 (a prohibition that would ultimately endure for 18 years), claiming that a moment of war and conflict was no time for “Spectacles of Pleasure, too commonly expressing lascivious Mirth and Levity.” A later and even stricter prohibiting act in 1648, which allowed theaters to be destroyed and actors to be arrested, said that all actors “are, and shall be taken to be Rogues, and punishable.”

Two-hundred-odd years later, James Buckley (1836–1920), an American Methodist minister and newspaper editor, penned an equally famous theater critique, noting,

Is it possible that the spectacle of women, painted, dressed as they are, with heaving bosoms, languishing glances, voluptuous attitudes, falling into the arms of men with whom they are on the verge, according to the play, of committing adultery, should make any other than the worst possible impressions? Persons of mature years and thorough self-mastery have found such spectacles to “tempt them to immorality”; while to expect the young to behold them without their imaginations being polluted is to defy reason and experience.

Prynne, who had condemned “Lascivious dancing. Amorous obscene songs: Effeminate lust-exciting Music. Profuse, inordinate lascivious laughter,” would surely have agreed.

Female roles were often a particular sticking point. In societies where it was the custom for women to appear on stage, critics assumed they must be women of low character. (Prynne’s description of female actors as “notorious whores,” taken as a reference to Queen Henrietta Maria, doomed him.) Methodist bishop John Heyl Vincent (1832–1920) commented in his 1892 book Better Not that theaters are

exhibiting women with such approaches to nakedness as can have no other design than to breed lust . . . getting us used to scenes that rival the voluptuous and licentious ages of the past.

If it was not the custom for women to appear, as in ancient Rome or in Shakespeare’s time, men dressed as women were condemned as cross-dressing “buffoons” (to quote Tertullian) or accused of “effeminate gesture, to ravish the sense; and wanton speech, to whet desire to inordinate lust” (as in a 1579 pamphlet by Stephen Gosson, The School of Abuse). Prynne also was concerned about the “gross effeminacy” and the aspects of costumes and sets that were “womanish . . . costly, fantastical, strange, lascivious, whorish, provoking unto lewdness.”

WORSHIPING THE DEVIL-GODS?

In the early church, the critique of idolatry was quite a literal one; theaters and other forms of public entertainment should not be patronized by Christians because they were devoted to and inspired by pagan gods, whom Christians had abjured in their baptism and saw as demonic.

Later antitheatrical authors often transferred this critique to Roman Catholicism and to other liturgical traditions (Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran). Prynne referred to “all our Roman Catholics, (who are much devoted to these Theatrical Spectacles).” Buckley’s survey of the attitude of different religious groups to the theater noted that the rot, as he would have seen it, ran deep in Catholicism:

In its ritual it makes more use of dramatic representation than any other body bearing the Christian name, and in some parts of the world, at certain seasons, actually dramatizes the scenes of the crucifixion.

Later he called out, in addition to Catholics, the same periods in English religion that Prynne had singled out for critique:

It is not pretended that attendance on the Theater is inconsistent with the general moral and religious character of the average Roman Catholic population of the world, or with that of the Church of England in the times of Henry the Eighth, Edward, Elizabeth, or of Charles the First and his son.

REJECTING UNREALITY

But beyond outward trappings of rich and revealing costumes, moral concerns that acting was too adjacent to prostitution and anxiety about the theater’s pagan origins and (later) Catholic associations, lay the most philosophical objection of all: plays are not Christian because plays are fictional.

Tertullian argued, “the Author of truth hates all the false; He regards as adultery all that is unreal.” Furthermore, Tertullian feared, fictional theatrical scenes would produce passionate responses in the watchers—a passion twice as bad because it was not aroused by a legitimate object:

For the show always leads to spiritual agitation. . . . When a tragic actor is declaiming, will one be giving thought to prophetic appeals? Amid the measures of the effeminate player, will he call up to himself a psalm?

Augustine’s Confessions describes this dynamic—a dynamic which, after his conversion, he looked back upon with regret:

Stage-plays also carried me away, full of images of my miseries, and of fuel to my fire. Why is it, that man desires to be made sad, beholding doleful and tragical things, which yet himself would no means suffer? Yet he desires as a spectator to feel sorrow at them, this very sorrow is his pleasure. What is this but a miserable madness?

Over a millennium later, Buckley used similar language to compare the unreality of the theater to alcoholic intoxication:

Improper sentiments and forms of expression will be imperceptibly imbibed, the imagination filled with unhealthy ideas, and the passions prematurely aroused and morbidly excited.

Like his antitheatrical predecessors, he found this passion doubly problematic because it had no real-life correspondence:

When such a man or woman returns to real life ordinary distress fails to move him, and they who weep over imaginary scenes leave suffering work people unpaid, and consider it annoying to be solicited for charitable objects.

Of course these antitheatrical writers did not speak for all Christians—or you would not be reading the rest of this issue. However, their arguments have not gone away; today they are just as frequently used to condemn movies, television, and even YouTube. Tertullian certainly could not have dreamed of YouTubers. But had he encountered them, he would have known what he should say. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is a senior editor of Christian History.Next articles

Heel kicking and holy jumping

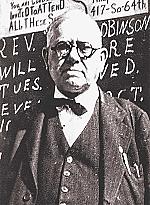

Some early twentieth-century preachers enhanced their oratory with theatrical flair

Abram J. Book“Merry Christmas, Mr. Scrooge”

The story includes references to Jesus as the “Founder” of Christmas

Edwin Woodruff TaitFrom drama to life

George and Louisa MacDonald’s family truly lived the Pilgrim’s Progress

Rachel E. JohnsonSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate