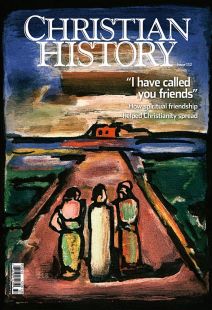

“As the heart of one man”

[Founders of the Baptist Mission—from James S. Dennis, Christian Missions and Social Progress (New York: Fleming H. Revell 1909)]

DID FRIENDSHIP CHANGE in the eighteenth century? Some scholars have argued that it did—as one historian, Keith Thomas, traces the history of friendship, he argues that it came in those years to be based “wholly on mutual sympathy, and cherished for its own sake rather than for its practical advantages.” Friends were understood to be “intimate companions, freely chosen, without regard to an ulterior end.”

While other stories in this issue make it clear that freely chosen intimate companions played an important spiritual role well before the eighteenth century, this phrase is a beautiful description of the circle of friends around pastor-theologian Andrew Fuller (1754–1815). Almost unknown today, in its own time this circle prompted far-reaching missionary efforts, despite some disagreements on how those efforts would be accomplished.

Biblical blacksmith

As the son of dairy farmers in Soham, Cambridgeshire, Fuller received only minimal formal education that ended around the age of 12. He was tall and sturdily built; members of the gentry like William Wilberforce (1759–1833), who deeply admired Fuller, found him to be “the very picture of a blacksmith” in his physical appearance and bearing.

Fuller mainly served as the pastor of a Baptist church in Kettering, Northamptonshire, and had been converted out of a hyper-Calvinist milieu. Common to many English Baptist communities of that day, hyper-Calvinism was a branch of Calvinism that laid extreme stress on the sovereignty of God and claimed that the gospel only needed to be preached to those already disposed to believe. The self-taught Fuller had to find his own way to a new and, he felt, more biblically sound position with regard to conversion, piety, and preaching.

In his memoir he later compared this theological struggle to trying to find his way “out of a labyrinth.” He came to the conclusion that, as he wrote in a public letter in 1810, “the true churches of Jesus Christ travail in birth for the salvation of men. They are the armies of the Lamb, the grand object of whose existence is to extend the Redeemer’s kingdom.”

His lack of formal education did not impede Fuller, who became by wide admission the finest theologian of the transatlantic Baptist community in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. David Phillips, a nineteenth-century Welsh biographer, called Fuller “the elephant of Kettering,” an allusion to the weighty theological influence that even before Fuller’s death was being described as “Fullerism.”

In 1792 Fuller and other Baptist pastors met in Kettering to discuss the need to spread the gospel, contrary to the tenets of hyper-Calvinism. Twelve of them signed a charter beginning the Baptist Missionary Society (called at first the Particular Baptist Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Amongst the Heathen). They chose John Thomas and William Carey (1761–1834) as their first missionaries. (You can see the signatures of Thomas, Carey, and Fuller and some of their colleagues on p. 28.)

Carey was already known as a strong proponent of worldwide missionary activity—a controversial position among Baptists. Earlier that very year he had written An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens (1792), which put forth theological and practical arguments for preaching the gospel to the unconverted. Carey had been converted from Congregationalism to the Baptists through his association with Fuller and his friends, and he had received adult believer’s baptism from Fuller’s friend and fellow Particular Baptist clergyman, John Ryland Jr. (1753–1825).

Carey may have been the “father of modern missions,” but his association with Fuller and Ryland grounded this missionary activity. They invited him to preach in local churches, welcomed him into a local association of Baptist preachers, and mentored him in the faith. While Carey’s missionary work takes center stage in stories today, the modern missionary movement owes much to the lifelong friendship between Ryland and Fuller—the two pastors who stayed home and sent Carey and other missionaries out.

A “long and intimate friendship”

Ryland and Fuller first met in 1776 as young men at an annual meeting of the Northamptonshire Association of Baptists. The two young pastors were wrestling with a number of extremely important theological issues, especially what they found to be the deadening effects of hyper-Calvinism on their Baptist community.

The two discussed at length how to pursue the renewal of their churches. (Fuller wrote later about the decline in membership among Baptists at the time: “Had matters gone on but for a few years [more], the Baptists would have become a perfect dunghill in society.”)

Within a year of meeting, the two were the closest of friends. After Fuller moved from Soham to Kettering in 1782, they were only 13 miles apart and had frequent opportunities to talk, to pray, and to spend time together until 1793 when Ryland became principal of Bristol Baptist Academy, more than a hundred miles away.

In this time before trains and automobiles, letters were the main way that Ryland and Fuller kept their friendship alive and intact. Maintaining a friendship through frequent letters was of course common in the nineteenth century. Ryland also kept up a lifelong correspondence with pastor and hymn writer John Newton; the older Newton once wrote to him, “I wish my letters may be a bridle to you and yours a spur to me.”

In 1816, the year following Fuller’s death, Ryland penned the first biography of Fuller. It proved popular: a second edition was published in 1818. In the introduction, Ryland wrote of his friendship

with Fuller:

Most of our common acquaintance are well aware, that I was his oldest and most intimate friend; and though my removal to Bristol, above twenty years ago, placed us at a distance from each other, yet a constant correspondence was all along maintained; and, to me at least, it seemed a tedious [painful and upsetting] interval, if more than a fortnight elapsed without my receiving a letter from him.

Their friendship, unbroken until Fuller’s 1815 death, was an obvious source of joy to both of them. In the year that he died, Fuller described his relationship with Ryland as a “long and intimate friendship” that he had “lived in, and hoped

to die in.”

Nine days before he died, Fuller asked one last request of Ryland: to preach his funeral sermon. Ryland agreed, though it was no easy task for him to hold back his tears as he spoke.

Toward the end of the sermon, Ryland reminisced about the fact that their friendship had “never met with one minute’s interruption, by one unkind word or thought, of which I have any knowledge” and that the wound caused by the loss of “this most faithful and judicious friend” would never be healed in this life. Ryland’s statement speaks volumes about the way these two men treasured their relationship and saw it as a means of human flourishing.

We read the same books

From the early days of their friendship, Fuller and Ryland quickly discovered that they shared, as Ryland put it, “a strong attachment to the same religious principles, a decided aversion to the same errors, a predilection for the same authors.”

In particular they both read the American theologian Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) and appreciated his thought regarding conversion and revival, spirituality, and missions.

They displayed one fundamental aspect of a good spiritual friendship: a union of hearts, and a related oneness of soul in a shared passion for the glory of Christ and the extension of his kingdom. Yet, as Ryland affirmed in his biography of Fuller, their “intimate friendship did not blind either of us to the defects or faults of the other; but rather showed itself in the freedom of affectionate remark on whatever appeared to be wrong.”

The two friends may not have had a minute’s interruption of their love for each other, but that did not mean that they did not differ. Ryland wrote that there was only “one religious subject” about which “there was any material difference of judgment” between the two friends. That subject was an extremely volatile one in the eighteenth-century transatlantic Baptist community: the twin issues of open and closed Communion and open and closed membership.

“Without . . . giving offence”

The vast majority of pastors and congregations in the Particular Baptist denomination, including Fuller, adhered to a policy of closed membership and closed Communion—that is, only believers baptized on adult profession of faith could become members of their local churches and only these baptized believers could partake of the Lord’s Supper in their meetinghouses.

Fuller wrote three short treatises on the subject: Thoughts on Open Communion (1800), Strict Communion in the Mission Church at Serampore (1814), and The Admission of Unbaptized Persons to the Lord’s Supper Inconsistent with the New Testament (published after his death in 1815).

Ryland, on the other hand, felt convicted that both the Lord’s Supper and membership in the local church should be open to all Christians, regardless of whether or not they had undergone believer’s baptism. When Ryland was the pastor of the College Lane Church in Northampton, for instance, one of the leading deacons of the church, a certain Thomas Trinder, did not receive believer’s baptism until six years after he had been appointed deacon. Fuller would never have tolerated such a situation in the church at Kettering.

However, Ryland and Fuller were secure enough in their friendship to disagree about this controversial subject without it destroying their fellowship. The only time it came close to doing so was in connection with the Baptist Missionary Society’s ecclesial practice at Serampore, India. And it is here that William Carey comes back into the story.

Carey, sent out to India in 1793, had moved from Calcutta to Serampore in 1801 to open a mission station. This station, headed by Carey along with Joshua Marshman (1768–1837) and William Ward (1769–1823)—all friends of Ryland and Fuller—adopted a policy of open Communion in 1805.

The Serampore missionaries knew of Fuller’s position, of course—his Thoughts on Open Communion had originally been addressed to them. But writing to him in 1805, the Serampore missionaries informed him that they had come to the conviction that:

[N]o one has a right to debar a true Christian from the Lord’s table, nor refuse to communicate with a real Christian in commemorating the death of their common Lord, without being guilty of a breach of the Law of Love.

They went on to affirm:

We cannot doubt, whether a Watts, an Edwards, a Brainerd, a Doddridge, a Whitefield, did right in partaking of the Lord’s Supper, though really unbaptized, or whether they had the presence of God at the Lord’s Table?

Deeply disturbed by this reasoning and the decision made by the Serampore missionaries, Fuller exerted all of his powers of influence and persuasion to convince Carey and his associates to embrace closed Communion at Serampore, which they eventually did in 1811. In The Admission of Unbaptized Persons to the Lord’s Supper Inconsistent with the New Testament, he would later write,

The best feelings of the human heart are those of love and obedience to God; and if I deny myself of the pleasure which fellowship with a Christian brother would afford me, for the sake of acting up to the mind of Christ, or according to primitive example, I do not deny the best feelings of the human heart, but, on the contrary, forego the less for the greater. It is a greater pleasure to obey the will of God than to associate with creatures in a way deviating from it.

In a pinch, it seemed, Fuller would have valued obedience over friendship—but his continued association with Carey and the others showed that he preferred to have both.

Ryland was not slow to criticize this reversal of policy by the Serampore missionaries. But he later said of his disagreement with Fuller: “I repeatedly expressed myself more freely and strongly to him, than I did to any man in England; yet without giving him offence.”

Neither did Carey, who also disagreed with Fuller’s position, take offence at Fuller—then or later. When he heard of Fuller’s death in 1815, he wrote almost immediately to Ryland and told him: “I loved him very sincerely. There was scarcely another man on the Earth to whom I could so compleatly [sic] lay open my heart as I could to him.”

A little band of brothers

In the end, though we most remember Carey’s name, the story of the friends who sent him out to the mission field—supporting him with prayers, donations, and guidance—is no less crucial.

Christopher Anderson (1782–1852), a Scottish Baptist leader, knew well Fuller’s circle of friends, and he thought they exemplified the kind of friendship essential to the spread of the gospel—united in a common mission to spread Christ, even if they sometimes disagreed on the means to accomplish it.

Anderson remarked after Fuller’s death in an 1822 letter to a colleague:

[I]n order to much good being done, co-operation, the result of undissembled love, is absolutely necessary; and I think that if God in his tender mercy would take me as one of but a very few whose hearts he will unite as the heart of one man—since all the watchmen cannot see eye to eye—might I be but one of a little band of brothers who should do so, and who should leave behind them a proof of how much may be accomplished in consequence of the union of only a few upon earth in spreading Christianity, oh how should I rejoice and be glad!

In order to such a union, however, I am satisfied that the cardinal virtues, and a share of what may be considered as substantial excellence of character, are absolutely necessary, and hence the importance of the religion which we possess being of that stamp which will promote these.

Such a union in modern times existed in [Andrew] Fuller, [John] Sutcliff, [Samuel] Pearce, [William] Carey, and [John] Ryland. They were men of self-denying habits, dead to the world, to fame, and to popular applause, of deep and extensive views of divine truth, and they had such an extended idea of what the Kingdom of Christ ought to have been in the nineteenth century, that they, as it were, vowed and prayed, and gave themselves no rest. CH

By Michael A. G. Haykin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #132 in 2019]

Michael A. G. Haykin is professor of church history and biblical spirituality and director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has written numerous books including One Heart and One Soul: John Sutcliff of Olney, His Friends, and His Times; Kiffin, Knollys and Keach: Rediscovering Our English Baptist Heritage; and “At the Pure Fountain of Thy Word”: Andrew Fuller as an Apologist.Next articles

Friends united in mission

Gospel-centered friendships abound in church history; here are some milestones for those we focus on in this issue.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitThe Meaux Circle and the Holy Triumvirate

Calvin’s ministry grew out of several partnerships in reform

Jon Balserak“A pure and holy love”

“On Spiritual Friendship” was a popular medieval expression of what it meant to be a friend to other believers

Aelred of RievaulxSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate