Another accidental revolutionary

MISSIONARIES SENT INTO THE COUNTRY under assumed names, taking obscure mountain passages in an effort to elude detection by the authorities along the border, provided with false papers and sent out secretly to their destination: sound like North Korea in the twentieth century? No—France in the 1560s.

[Facade of Genevan church]

Secret agent men

From miles away in Geneva, John Calvin (1509–1564) and Theodore Beza (1519–1605) were discipling French Calvinists. They created and fostered Reformed communities devoted to the Genevan vision by smuggling books on Reformed theology into the country and sending to France Reformed ministers who had been trained in Geneva. Once these ministers arrived at the churches to which they were being sent, they would preach and conduct services, often secretly as Calvin recommended. All of this, of course, was illegal. In fact, professing the Reformed faith in France was illegal.

In 1561 Beza, in a letter to fellow reformer Ambroise Blaurer, referred to these Reformed churches in France as “the colonies”; that is, colonies of Geneva. Through all these clandestine activities, Calvin and Beza were trying to recolonize their homeland.

They were both Frenchmen who believed they brought the one true Gospel that they loved into a country that they loved—the land of their births. They saw themselves as ministers of the Gospel. Neither of them represented foreign mercenaries or assassins. They were not Italian or Spanish or English, traditional enemies of the French.

Yet many French people viewed them as sworn enemies—wicked men who sought the destruction of the French nation and were likely to bring upon her the wrath of God because of their “heretical” teachings. Both men had fled their homeland to escape persecution on account of their religious beliefs. They left at different times, Calvin in 1533 and Beza in 1548, but by the 1550s they were both working for the “evangelical gospel” from the conveniently located city of Geneva.

Geneva sits at the border of eastern France; from there the two pastors and theologians could work effectively to nurture French Reformed churches. Because they knew the French authorities were wholly opposed to their plans for evangelizing the country, they employed various measures designed to hide what they were doing.

The sending of ministers into France and the fostering of “heresy” increased tensions in the country. Local disputes and skirmishes broke out, and eventually blood was shed on a much larger scale, with the first of the so-called French Wars of Religion commencing in the spring of 1562.

France was not their only target. From the relative safety of Geneva, Calvin and Beza also sent ministers to other parts of the continent and the British Isles and wherever the Reformed faith spread. There were, by the 1560s, Reformed churches in Scotland, England, the Netherlands, Eastern Europe (Hungary, specifically Transylvania), and parts of Germany (see “A faith that could not be contained,” pp. 19–23). Within a century English Puritans would carry the Reformed faith to the New World.

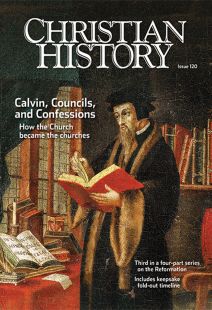

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

This expansion was not by any means solely the work of Geneva, nor solely John Calvin’s movement. It flowed from the work of many individuals, chief among them Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) and Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575) in Zurich, Johannes Oecolampadius (1482–1531) in Basel, Martin Bucer (1491–1551) in Strasbourg, and, much later, Francis Turretin (1623–1687) and Benedict Pictet (1655–1724) in Geneva. But Calvin formed a central part of its spread. To understand his life, we need first to understand the European reformations occurring by the time he was a teenage boy.

Which Reformation?

Why the plural “reformations”? Various efforts at reforming the church were going on simultaneously by the mid-1520s and early 1530s, some from within the Catholic Church (more on that in issue 122—Editors).

When people think of the Reformation, they think almost instantly of Martin Luther and his posting of the 95 Theses on the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg. But there were others. Around the same time, Zwingli, serving as a priest in Zurich, was working earnestly to purify worship in the Swiss Confederation, having also come to understand (independently of Luther) the gospel of God’s free grace and the doctrine of justification by faith alone which we all associate with Luther and Lutheranism.

Likewise there arose in places like Zurich and Wittenberg other rival movements, or clusters of related movements, which were thorns in the sides of Luther and Zwingli: they were known as Anabaptists (see CH 118).

France was not immune to these ideas. There individuals working for change within the Catholic Church represented yet another reform movement in Europe, referred to broadly as “French evangelicalism.” Out of this movement arose Calvin, Beza, and other important Genevan reformers like Guillaume Farel (1489–1565) who would eventually persuade Calvin to make his home in Geneva (see “The king, the emperor, and the theologians,” pp. 48–52).

Everything old Is new again

These French reformers found their roots in the Italian Renaissance, a recovery of ancient art and culture that swept across southern Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It featured thinkers and artists like Petrarch (1304–1374), Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375), Lorenzo Valla (1407–1457), and Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494). As a result Europeans began drinking from the fresh springs of ancient Greek and Roman thought with renewed vigor.

This enthusiasm for ancient authors and ideas moved north in the early sixteenth century with Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) and Rudolph Agricola (1443–1485) and made its way into France, where thinkers like Guillaume Budé (1467–1540) picked it up. Budé applied the new rigorous methods of study shaped and honed by Italian humanists to investigating things like antique coinage and to legal history.

But humanism did not stop with coins and laws. With an eye on reforming the French church, a group of influential French scholars and churchmen headed by Farel, Guillaume Briçonnet (1472–1534), Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (1455–1536), Josse van Clichtove (1472–1543), and Gérard Roussel (1500–1550) gathered together, excited to apply these new methods to studying the Bible and the writings of the early church. The group was called the Circle of Meaux, after the town where they met and of which Briçonnet eventually became bishop.

When Luther’s writings began to pour into France in the late 1510s, the Circle of Meaux was ready to grab hold of Reformation ideas. Luther’s The Freedom of a Christian, An Open Letter to the German Nobility, and The Babylonian Captivity of the Church (all published in 1520) spread rapidly and were widely read. Reading Luther became harder after 1521 when he was excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church, but it was still possible.

Now inspired by Luther, members of the Circle of Meaux, particularly Jacques Lefèvre, began to translate the Bible into French. His New Testament was published in Paris in 1523 and distributed by Briçonnet and others. In 1535 Pierre Robert Olivétan produced a translation of the whole Bible in French.

Most members of the Circle of Meaux were Catholic and remained Catholic all their lives. But they were Catholics keen to work for the reform of their church and, as such, tended to exhibit concerns for matters similar to the Wittenberg and Zurich reformations. They were critical of the buying of indulgences and the manner in which the sacraments were practiced, of superstitious devotions, and of the moral failings of the clergy and church. They also urged new understandings of the doctrine of justification, the nature of faith, and the purity of devotion.

From 1520 onward their words turned harsher, with more intense and unremitting criticism leveled at the pope and Roman Catholic bishops. With this harsher turn, divisions began to appear. Essentially three groups emerged: reformist clergy like Bishop Briçonnet, who wanted to see moral change but worked for little else; a group that favored evangelical ideas but stopped short of taking a hard-line stance; and evangelicals such as Farel who decided that devotion to the Christian gospel required separation from the traditional church.

Both Calvin and Beza were born into this France, and Calvin may have been linked with this third group as a young man. It was certainly the group that sided with him and Beza from the 1540s onward.

A “sudden conversion”

John Calvin was born in 1519 outside Paris, in Noyon in Picardy. As a young man, he studied at the Collège de la Marche, in Paris. It is believed that, after completing his coursework there, he entered the Collège de Montaigu. His travels during the mid-1520s took him from the University of Paris to the University of Orléans, to the University of Bourges, and back to the Collège Royal in Paris—due, in part, to his changing his course of studies, at his father’s request, from theology to law.

During these years Calvin developed an interest in Renaissance humanism, which led to his writing one of his first works in 1532, a commentary on De Clementia (On Clemency) by the Roman philosopher Seneca. Calvin effectively published this book with his own money, which ended up being something of a disaster. He was unable to recoup his losses and was embarrassed by the poor response his commentary received.

But the future course of Calvin’s life would not revolve around Seneca. At some point around this time, Calvin experienced an important alteration of his religious views. An unresolvable enigma remains surrounding the timing, the character of, and the influences upon his conversion away from Roman Catholicism. It has been subjected to painstaking study with surprisingly little to show for it.

Calvin wrote extensively, but little about himself. He wrote massive numbers of texts, letters, sermons, and lectures, many of which were published in 59 enormous volumes in the nineteenth century. In all those 59 enormous volumes, only two provide moments of possible autobiography, and one of them is disputed. It seems he was not much interested in leaving behind his own story.

But Calvin’s preface to his commentary on the Psalms is unambiguously autobiographical. Written in 1556 it recounts events that took place approximately 30 years earlier. By the time he wrote this preface, he had become internationally renowned, loved and hated by many. It is impossible to imagine how this might have affected the contents of this preface. But, for good or ill, it is all we have from his own pen.

In it, he describes himself as having experienced a “sudden conversion.” This experience (subita conversio in Latin) has been interpreted by some to mean that he had a Damascus Road conversion like the apostle Paul. But most scholars now do not think that.

Rather his language almost certainly means that he found himself suddenly or surprisingly open to new thinking; open to strains of thought to which he had previously closed his mind. It is doubtful that he suddenly converted wholesale to “Protestantism” (a label that would have been unknown to him at that time).

Whatever happened, it led to the events of All Saints’ Day in 1533. On that day Calvin’s friend, Nicolas Cop (1501–1540), the rector of the University of Paris, delivered an address at the commencement of the academic year that roused suspicion because of its “Lutheran” themes (a generic term for heresy).

King Francis I responded to the incident by attempting to round up everyone in the city associated with “Lutheranism,”including Calvin. In response not only Cop, but also Calvin and numerous others, fled Paris. One story goes that Calvin escaped the day after the lecture by climbing out a window on knotted bedsheets, then disguising himself as a vine dresser and walking out of the city with a hoe slung over his shoulder.

Calvin wandered around various parts of Europe before arriving in Geneva in July of 1536. There he found Farel, a fellow expatriate and preacher who had recently read the newly published first edition of Calvin’s short theological handbook, Institutes of the Christian Religion. When Farel learned that the author of this latest publishing sensation was in his city, he went to Calvin’s dwellings and urged him to stay and help with reform efforts.

Intending to stay only one night in Geneva, Calvin was reluctant, but Farel was persistent, if unorthodox in his methods. He famously swore a curse on Calvin if he were to depart and go off to read books in a library in Basel (which apparently was Calvin’s plan). The rest, as they say, is history. Calvin stayed and, apart from being expelled for a brief period (1538–1541), remained in Geneva the rest of his life.

“The common cause of all the godly”

In Geneva Calvin lived the life of a busy pastor (see sidebar, p. 9). He preached on average more than 200 times a year during his more than 30-year ministry. This still, rather amazingly, gave him time to produce new editions of his Institutes as well as many other works.

Calvin was prolific and, in both French and Latin, proved to be a clear and passionate writer. In total he produced five major Latin revisions of his most famous work, the Institutes (1536, 1539, 1554, 1550 and 1559; see p. 18 for an excerpt). There was no French translation of the 1536 Latin edition, but the later editions were translated into French, the definitive one in 1560.

The work as published in 1536 consists of six chapters, which discuss the law (de lege), faith (de fide), prayer (de oratione), the sacraments (de sacramentis), the five false Catholic sacraments (quo sacramenta … reliqua), and Christian freedom (de libertate Christiana). The work also concludes with a brief examination of the nature of government and the office of the civil magistrate. The structure has been linked with Martin Luther’s Small Catechism of 1529.

The Institutes, it has been argued, is a theological work with a political subplot—a position that garners some support from Calvin’s preface to his commentary on the Psalms. In it he claims that he wrote the Institutes to explain to the French king, Francis I, the true character of the faith of those the king had put to death in 1534 in an attempt to rid France of heretical groups.

Calvin wished in his Institutes to show the French king that French evangelicals posed no threat to the religious and civil order of the realm. In fact he included in every edition a prefatory letter addressed to the king and defending his movement:

Let it not be imagined that I am here framing my own private defense, with the view of obtaining a safe return to my native land. Though I cherish towards it the feelings which become me as a man, still, as matters now are, I can be absent from it without regret.

The cause which I plead is the common cause of all the godly, and therefore the very cause of Christ—a cause which, throughout your realm, now lies, as it were, in despair, torn and trampled upon in all kinds of ways. …

Your duty, most serene Prince, is, not to shut either your ears or mind against a cause involving such mighty interests as these: how the glory of God is to be maintained on the earth inviolate, how the truth of God is to preserve its dignity, how the kingdom of Christ is to continue amongst us compact and secure. The cause is worthy of your ear, worthy of your investigation, worthy of your throne.

Children of Geneva

Calvin soon established Geneva as a major center for the Reformation, with compatriot Beza joining him in the city in 1558. But the period Calvin spent in the city was hardly an unbridled success.

After arriving in 1536, he quickly found himself on the wrong side of powerful families there who regarded him and Farel as foreigners (which they were) and disruptive (which they also were). Accordingly Calvin and Farel were expelled from Geneva on April 23, 1538. But many Genevans began almost immediately asking Calvin to return, which he did more than three years later on September 13, 1541.

But from 1541 until the summer of 1555, many of Calvin’s plans for the city were foiled by enemies known as les enfants de Genève, or “the children of Geneva.” (You can see a picture of Calvin famously refusing Communion to some of them on p. 14.) Finally in June of 1555, they rioted and were all either exiled or put to death.

A change in the character of the population made this turn of events possible. Due to many refugees moving from France to Geneva to escape persecution (just as Calvin himself had done earlier), Geneva was, by the early-to-mid 1550s, populated by many supporters of reform, who purchased citizenship and ended up obtaining voting rights (see “Religion of the refugees,” p. 13).

With these enemies gone, Calvin began a more cooperative relationship with the Genevan Little Council (the main force in civil government). From that time onward he managed to build a city praised famously by John Knox (c. 1513–1572) as the “most perfect school of Christ since the time of the Apostles.”

With the enfants out of the way, Calvin and his fellow ministers, the Venerable Company of Pastors, could enforce Christian beliefs and practices within the city. This enforcement covered a much wider range than we could realistically imagine today.

They shaped everything from economic matters to legal, cultural, and educational regulations. Taverns were closed, though they were eventually reopened; most forms of dancing were forbidden. People could be, and were, put to death for everything from heresy to homosexuality, divorce, and witchcraft.

Of crucial importance to the work of the ministers was a quasireligious committee called the Consistory, made up of Christian ministers and of members of the civil government, with Calvin usually taking the helm. It served as a morals court for the city.

The Consistory heard cases involving Genevans of all social ranks, high and low, men and women. It dealt with marital disharmony, gambling, slander, adultery, murder, and anything else deemed to have breached the morals appropriate to a Christian commonwealth. It had the ability to dispense punishments of various kinds including excommunication, but it turned over anyone guilty of a capital crime to the civil government to be dealt with.

Consistory records range far and wide on religious and moral matters: for example, they record a woman who was asked “about frequenting of sermons, etc. [i.e., attending church], and about the child her son has had by her maid” and admitted that “she says the Pater [Lord’s Prayer] in the new Reformed manner, but does not know the Credo [creed]”; another woman who was “remanded as outside the faith” because she “did not want to renounce the Mass”; an unwed mother who “did not say her Pater well, and she goes to sermons on Monday and other days not”; and a man who was asked “about the wizard he had in his house and why.”

Serving the church of God

The Consistory was considered so successful it ended up being imitated throughout France and elsewhere. Which brings us back to where our story began: with the sending out of missionaries from Geneva to the rest of Europe, forever linking Calvin’s name with the Reformed faith and building a world-transforming movement.

John Calvin died in Geneva in 1564, but his spiritual descendants number in the millions and hail from France, the British Isles, Eastern Europe, and everywhere his “missionaries” landed. In his Institutes he wrote, “Wherever we find the Word of God surely preached and heard, and the sacraments administered according to the institution of Christ, there, it is not to be doubted, is a church of God.”

He would no doubt have considered hundreds of thousands of churches preaching the Word of God and administering the sacraments as a pretty good trade-off for listening to Farel and staying in Geneva, even though he didn’t get to read all the books he wanted in Basel. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jon Balserak

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Jon Balserak is senior lecturer at the University of Bristol and author of John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet and Calvinism: A Very Short Introduction.Next articles

Calvin, Councils, Confessions, Did you know?

Calvin the teacher, Menno the preacher, Elizabeth the queen, and those unpronounceable French Protestants

the editorsEditor's note: Calvin, councils, and confessions

Setting out to renew the church, the reformers divided and subdivided it

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate