A faith that could not be contained

[Reformers looting churches in Lyons, France]

THE STORY OF CALVINISM’S emergence and the development of the Reformed tradition is forever tethered to Geneva. And yet Reformed Christianity in Europe reached well beyond those walls of refuge. Even the great reformer of Geneva, John Calvin, was not a Genevan himself, but a French refugee seeking asylum from persecution in his native country.

It is estimated that by 1600 around 10 million people worshiped in Reformed churches, a 2,000 percent increase in just 50 years. Established churches embraced the Reformed tradition in Scotland, England, Béarn (a self-governing province located in modern-day France), and about a dozen German principalities. The Reformed Church was privileged by the state in the United Provinces of the Netherlands, and tolerated churches grew in France, Hungary, Poland-Lithuania, and the Rhinelands, despite being a minority faith.

As the Protestant torch was passed to the second generation of leaders, the contribution of Reformed Christians to renewing the zeal and reach of the movement throughout Europe was unparalleled. That story is tied most of all to France.

The singing protestors

Imagine standing in Paris before the royal palace at the Louvre in the year 1558, well before it was transformed into a museum. A crowd of four to five thousand people joins you. Their voices fill the space with the singing of the Psalms—a mark of both their Protestant conviction and their open defiance of royal policies against the evangelical faith. The Psalms were the only songs sung in French Protestant congregations, and the earliest French martyrs had sung them as they were burned at the stake.

Day after day psalm-singers demonstrated. Soon the movement began to attract the support of powerful people, including Anthony of Navarre of the House of Bourbon (1518–1562), the highest-ranking noble in the land outside of the king’s immediate family. Soon Protestant sympathizers surfaced even within the royal family and the Parlement of Paris (which, despite its name, was more like a supreme court).

The very next year, 1559, saw the historic meeting of the first national synod of the French Calvinist churches in Paris. Thanks to the foundational work of John Calvin, Theodore Beza, and Pierre Viret (see “Another accidental revolutionary,” pp. 8–15), the synod embraced the Gallican Confession, the official confession of the French Reformed Church.

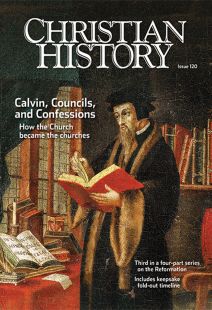

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

And soon the French Reformers got another boost with the unexpected (and in their view providential) death of one of their chief persecutors, King Henri II. In a rare jousting accident, splinters from a lance lodged in Henri’s brain. He was succeeded by his sickly 15-year-old son, Francis II, who also died unexpectedly of an ear infection on December 5, 1560. For French Protestants, called “Huguenots” by this time (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover), the sudden death of two persecuting kings confirmed God’s plan to establish his “true church” in France. With the nobility of France divided, it was only a matter of time before civil war erupted, known to history as the French Wars of Religion.

A Christmas present

On Christmas 1560 the Reformed cause gained the public support of a noble figure who would prove to be key to Protestant advancement—Jeanne d’Albret, queen of Navarre (1528–1572), daughter of Marguerite d’Angouleme (Francis I’s sister and Henri’s widow). In 1562, after the death of her husband, Anthony, Queen Jeanne became the sole ruler of the principality of Béarn, just south of France in the Pyrenees Mountains.

There she began to abolish Catholicism in her kingdom, beginning with the turning over to the state of church property in 1566 and culminating with the abolition of the Mass in 1571. During the Third French Civil War of 1568, she herself victoriously led Huguenot troops at La Rochelle. A few years later, she presided over the Synod of La Rochelle where all the secular leaders of French Protestantism and their Dutch allies gathered. It was this level of leadership that won her the unwavering support of Calvin, who heralded Queen Jeanne as “our Deborah” (a title similarly given to Protestant queen Elizabeth I of England).

Jeanne’s son, Henri of Navarre (1553–1610), was crowned King Henri IV of France in 1572. Political intrigue famously forced him to renounce his Protestant convictions to assume the throne, but he nonetheless committed to ending France’s religious wars, passing the Edict of Nantes in 1598 which granted Huguenots legal permission to practice their faith. Jeanne’s daughter and Henri’s sister, Catherine of Bourbon (1559–1604), also emerged as a Reformed leader of France among this new Protestant generation.

Thanks to the Bourbon family, French Protestantism had come a long way since its inception among a small circle of clerics and humanist scholars in Meaux, France, and had persisted despite the royal persecution following the 1534 “Placard Affair.” Even after the horrific massacre of roughly 20,000 Protestants throughout France on St. Bartholomew’s Day 1572, Reformed Christians survived to reap the benefits of the Edict of Nantes—for a time.

Their churches thrived in what has been described as the “Huguenot crescent,” reaching from Poitou to Dauphiné and numbering just under one million members. They became increasingly reliant upon the leadership and support of Calvin’s Geneva over the course of the century. But they would face the greatest challenge to their survival in the 1600s, as French kings placed increasing restrictions on their freedom of worship. Though they could not imagine it as they sang their Psalms, in 1685 the Edict of Nantes would be revoked.

“God help us tell the story”

These Reformed communities of France were linked to the emergence of Dutch Reformed tradition, which also developed despite heavy persecution. In 1523 monks at the Augustinian monastery in Antwerp were arrested for embracing Luther’s dangerous ideas; those who refused to recant were executed in Brussels that July and became the first martyrs of the Protestant Reformation. Luther wrote the first Reformation martyr hymn in their memory. It begins: “A new song be by us begun, / God help us tell the story, / To sing what our Lord God hath done … at Brussels in the Netherlands / Hath He made known His wonders / Through two mere boys, right youthful lads… .”

Many factors made the Netherlands receptive to the spread of the Reformation: similarities between Dutch and the Low German spoken in northern Germany, bustling trade networks, high literacy rates, and booming cities. Luther’s works were quickly translated into Dutch in greater quantities than anywhere else in Europe.

But under the ruthless repression of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (who also ruled Spain and the Netherlands) and his son Philip II, it took many decades for the evangelical movement to take hold. Scholar Philip Benedict once noted, “The Netherlands was one of the first parts of Europe to be touched by Protestantism but one of the last to witness the establishment of a Protestant church.” By 1555 the Netherlands had created more Reformation martyrs than any other country in Europe.

Protestants fled Hapsburg persecution and went abroad to Geneva, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, London, and Emden, embracing Reformed theology and church structures. Queen Elizabeth welcomed them in England, much to the consternation of Charles V. Secret Calvinist churches arose in the Dutch commercial areas of Amsterdam and Flanders; Antwerp became the southern center of the Dutch Reformed movement, and Emden was heralded as “Geneva of the north.”

Meanwhile French-speaking Walloon provinces located in the southern Netherlands were reading Calvin’s works in their original language and circulating large numbers of forbidden religious texts. French-speaking Guy de Bray (1522–1567) became known as the “Reformer of the Netherlands,” penning the Belgic Confession in 1561—modeled after the Gallican Confession of 1559—which is still the doctrinal standard of Dutch Reformed churches in Holland, Belgium, and America. (He supposedly threw a copy over a castle wall to get the Spanish government’s attention.)

But Dutch Protestants did not stop with writing, reading, and smuggling. In 1566, spurred on by the organization of the Dutch church (in synods, like France’s) as well as the departure from the Netherlands of Philip II and his Spanish army, the Dutch Revolt erupted in Antwerp. Shocking acts of iconoclasm devastated church structures and images throughout the city.

That year came to be known as the “Wonderyear” because of the establishment of religious freedom and Reformed practices. But this newfound freedom barely lasted the year. Philip regrouped, and his so-called Council of Blood condemned roughly 10,000 people to death for Protestant and anti-Spanish sympathies, though perhaps only about 1,000 sentences were carried out.

Choosing exile over martyrdom, many Dutch Reformed communities continued to fight against persecution. Dutch Reformed Church order and liturgical practices were confirmed at the Synod of Emden in 1571. Meanwhile Dutch prince William of Orange defended the Protestant cause against Philip from the sea—stealing Spanish commerce, seizing coastal cities, and attacking Spanish fleets.

He successfully brought Spain to the brink of recession, and in 1581 seven territories of the Netherlands separated from Spanish rule and became the United Provinces or the Dutch Republic. Not until the end of the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) and the Treaty of Westphalia would this republic finally be recognized and the Reformed Church made the state-supported church of the region.

Watch out for those Calvinists

In the Holy Roman Empire itself, Charles V had his hands full from the very first day of his rule with the political and religious turmoil unleashed in the empire by Martin Luther’s actions. Often bound to appease the Lutheran loyalties of certain key princes (see “From Luther to the Lutherans,” pp. 34–38), he could not implement in German lands the level of persecution he had begun in the Netherlands.

In 1555 Charles passed the famous Peace of Augsburg before abdicating his throne to his brother. That peace legally permitted the existence of Lutherans and Roman Catholics, but excluded both radical reformers and the Reformed faith now sweeping Europe. There was much concern that “crypto-Calvinists,” or Lutherans with Calvinist sympathies, were lurking in every region. As in Holland it was not until the Peace of Westphalia (1648) that Calvinist communities and rulers in the Holy Roman Empire were officially recognized and legally protected.

But in 1561 Reformed Christianity in the Holy Roman Empire gained a prominent supporter: the elector of Palatine, Frederick III (1515–1576), who chose to accept the Reformed faith. Nicknamed “The Pious” he commissioned Reformed professors of theology at the University of Heidelberg to write a catechism to establish a common identity for the churches within his region. Heidelberg would become one of the most important education centers for Reformed pastors, next to Geneva’s Academy. And, in 1563, the Heidelberg Catechism was born and became one of the most widely embraced confessional statements of the Reformed Church throughout the world (see “God our only comfort,” pp. 39).

The church of the strangers

In the case of Eastern Europe, it was not a ruler but a battle that paved the way; the Battle of Mohacs (1526), where the Ottoman Empire defeated the Hungarian monarchy and Hungarian Catholics, allowed the Reformed faith to take hold in Hungary and Transylvania in the late 1550s.

Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575), Zwingli’s successor in Zurich, was particularly instrumental in guiding the Hungarian church, which eagerly embraced Calvin’s catechism, along with Bullinger’s Second Helvetic Confession (1566) and the Heidelberg Catechism. Reformed churches in Slavic and Hungarian regions often owed their existence to local reformations supported by the nobility.

One such nobleman and reformer was John a Lasco (1499–1560), Polish born but a far-ranging traveler. He helped preserve and form the Reformed identity of East Friesland in the Holy Roman Empire and served as the foreign superintendent of French and Dutch refugee churches located in London—united under the name “Church of the Strangers” as the first church ever organized in England outside of normal parish structures.

Called back to Poland in 1556, Lasco encouraged the growth of Calvinism there among the middling nobility. He died in January 1560, supposedly whispering the words “My Lord and my God” and slipping away as the evening sun sank over the city of Kaliz. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Jennifer Powell McNutt

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Jennifer Powell McNutt is associate professor of theology and history of Christianity at Wheaton College and the author of Calvin Meets Voltaire.Next articles

God our only comfort: German confessions

Excerpts from the Book of Concord and the Heidelberg Confession

variousThe rest of the story

The Reformation in England and Scotland took two very different paths

Calvin LaneSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate