Calvin, Councils, Confessions, Did you know?

[Caricature of Louis XIV, the "Sun King," de Louis Le Grand, 1691 (mezzotint) (b/w photo), Dusart, Cornelis & Gole, Jacob (1660–1737) (attr. to) / Bibliotheque de la Societe de l’Histoire du Protestantisme Francais, Paris, France / Archives Charmet / Bridgeman Images]

A momentous detour

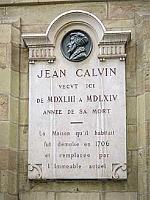

John Calvin trained first as a lawyer; his first published book was an academic commentary on ancient philosopher Seneca. He meant to merely stop in the Swiss city of Geneva for a single night in 1536 (avoiding hostilities raging between the king of France and the Holy Roman Empire). But Guillaume Farel convinced him to stay, which he did for 25 years, becoming the city’s most famous person. Even so, he was not granted citizenship until five years before his death. Scottish reformer John Knox visited Geneva in 1554 and wrote to an English friend, “It is the most perfect school of Christ that ever was in the earth since the days of the Apostles.”

Colleague, friend, and pastor

Although he never met Luther, Calvin esteemed him very highly. To Heinrich Bullinger (see p. 48), he wrote: “Even if he were to call me a devil I should still regard him as an outstanding servant of God.”

Once when Calvin asked one of a pair of students to deliver a letter to his friend Pierre Viret, he noticed that the second student was jealous at not being the messenger. Calvin quickly dashed off a second letter to Viret containing the request that Viret pretend it was a valuable letter.

Calvin encouraged congregational psalm-singing in the church at Geneva. Like Luther, he viewed music as a gift of God and personally put to music a number of the psalms. During the course of his ministry in Geneva, Calvin lectured to theological students and preached an average of five sermons a week (see p. 9).

An unmarked grave

Calvin gave strict instructions that he be buried in the common cemetery with no tombstone. He wished to give no encouragement to those who might make it a Protestant shrine. He continued to work even on his deathbed, though his friends pleaded with him to rest. He replied: “What! Would you have the Lord find me idle when he comes?” Calvin’s seal pictured a burning heart in a hand and was accompanied by this motto: “Promptly and sincerely in the work of God.”

She loved her mother

There are few surviving records of Elizabeth I referencing her executed mother, Anne Boleyn. But in a painting from 1545 of Henry VIII showing his third wife, Jane Seymour, and his children, Elizabeth wears her disgraced mother’s pendant. She later adopted Anne’s heraldic emblem and one of her mother’s mottoes, “Always the Same” (Semper eadem).

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Hu-gue-who and Menno why?

French Protestants’ odd nickname, “Huguenots,” may come from a spirit called King Huguon, believed to haunt a city gate in Tours at night. Protestants held their illegal religious services near that gate after dark.

And why, like many pop stars, is Menno Simons known only by his first name? “Simons,” or “Simonszoon,” means simply “son of Simon” and was seldom used. Some Anabaptists gradually took on the label “Mennisten” (followers of Menno), and it stuck. Long years of steady leadership and his many publications sealed the deal. Most Dutch Anabaptists prefer today to be called “Doopsgezinden” (“baptism-minded”) to distance themselves from some of his views.

Menno claimed that he had not read the Scriptures until two years after his ordination at age 28: “I feared if I should read them they would mislead me. Behold! Such a stupid preacher was I for nearly two years.” But his later writings each begin with I Corinthians 3:11, “For no one can lay any foundation other than the one that has been laid; that foundation is Jesus Christ.” He wrote in The Blasphemy of Jan Van Leiden, “It is forbidden to us to fight with physical weapons.… This only would I learn of you; whether you are baptized on [i.e., in service to] the sword or on the Cross?” CH

Some of these entries are adapted from CH issues 5, 12, and 71.Mary Sprunger contributed to the entry on Menno.

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Next articles

Editor's note: Calvin, councils, and confessions

Setting out to renew the church, the reformers divided and subdivided it

Jennifer Woodruff TaitUnited with Christ in eternity and at the table

Calvin’s influential thoughts on predestination and the Lord’s Supper

Raymond A. BlacketerSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate