The rest of the story

[William Laud]

AFTER LUTHER and others burst onto the scene in the late 1510s, the next decades witnessed division upon division. But the second half of the century demanded clarity. If we asked a sixteenth-century believer what it meant to be a Calvinist, the answer would easily come back: to accept the 1561 Belgic Confession (see “A faith that could not be contained,” pp. 19–23). To be a Lutheran? To accept the 1580 Book of Concord (1580; see “God our only comfort,” p. 39). “Confessionalization” is how scholars refer to the process by which major reformers composed summary statements of Christian belief, and individuals and communities rallied around them: the denominations we know today resulted from this process.

But what about England? Can the question be answered so easily there? There has long been a pervasive sense that England’s reformation was the exception; that the sixteenth-century Church of England was more accommodating and less doctrinally concerned than other Protestant bodies. The narrative usually runs that after heady experiments with Reformed Protestantism in the short reign of the boy king Edward VI (1537–1553) followed by the Catholic reaction of Queen Mary (1516–1558), Elizabeth Tudor (1533–1603) settled her kingdom and church along a balanced via media, a tolerant middle way incorporating the best of both Reformed and Catholic worlds. But there is much more to the story.

We’re reformed too

Elizabethan England had, broadly speaking, a Reformed church. Most official Church of England doctrinal statements (the 39 Articles of Religion, two Books of Homilies, and the 1559 Book of Common Prayer) generally harmonized with Reformed Protestantism. Unlike the Continent the English had bishops, but that didn’t necessarily disqualify them from being Reformed; Calvin, though he had no bishops himself, had said that bishops for large territories might be expedient. During the reign of Elizabeth, Archbishop John Whitgift (c. 1530–1604) had his clergy read the solidly Reformed theology of Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1575), Zwingli’s successor. When the pace-setting Reformed Synod of Dort convened in 1618, representatives from the Church of England unsurprisingly took their rightful place at the table.

Yet, less than a hundred years after the Synod of Dort, the average member of the Church of England would perceive the English tradition to be distinct from continental Reformed churches, speaking of the English church as something exceptional. How did that happen? The root is worship.

Beginning to pray like Protestants

Issued in 1549 during the reign of Edward VI, the first edition of the Book of Common Prayer represented a seismic shift from the multiple medieval forms of the Mass. However it was still one step in a gradual approach; Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, a committed yet careful reformer, believed that change would be better accepted if achieved incrementally. While shrines were destroyed and religious imagery whitewashed, vestments and altars continued to exist.

But by 1552 a new edition of the prayer book made progress toward Reformed Protestantism clear for all to see. Ties between Cranmer and continental reformers like Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli (1499–1562) had deepened, and this second prayer book resembled the Swiss and South German Reformed tradition. Instead of the “canon” (a lengthy, central prayer of consecration in the Eucharist), the minister simply told the narrative of the Last Supper, and then the people immediately received bread and wine in remembrance of the self-sacrifice of Christ on Calvary.

How people worshiped looked different too. The 1552 prayer book required clergy to wear only a surplice (a white gown). Other vestments were banished. A moveable wooden table replaced the stone altar; communicants knelt around the table to receive loaves of bread, not wafers, and to drink wine, not from a chalice, but from a deep cup.

However this program was derailed when the young king died, likely of tuberculosis, in 1553, and his older half-sister, Mary, became queen. She set to work reconciling England with the papacy and burning many Protestants who had not fled upon her succession, notably Cranmer in 1556. Death also cut short Mary’s reign, and thus Henry’s middle child, Elizabeth, became queen in 1558. Many who had fled Mary’s England returned home.

During the reign of Edward, Cranmer had slowly dismantled Catholic England bit by bit. When Cranmer’s exiled colleagues came home, they assumed this would continue: wearing a surplice, using a ring in marriage, and making the sign of the cross in baptism would soon be discontinued.

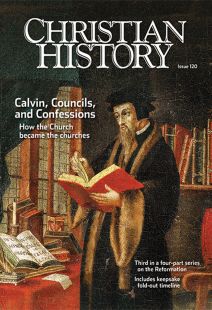

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

These returned exiles, however, were disappointed to learn that Elizabeth effectively froze the Edwardian project in amber. Her 1559 prayer book represents not a stepping stone, but a stopping point. In the generation afterward, those returned exiles continually, and unsuccessfully, lobbied for change—and the Puritan party emerged searching for a more “purified” church.

But even this isn’t the end of the story.

Knox: #1 fan of the Swiss

Scots reformer John Knox (1513–1572) had proven a nuisance for Cranmer in the reign of Edward. Knox considered kneeling during Communion to be idolatrous, and he had sparked a debate about it. In response the English church issued a rubric explaining that kneeling meant “humble and grateful acknowledging of the benefits of Christ, given unto the worthy receiver” and intended no “Catholic” adoration of the bread and wine. Knox then found his way to Geneva where in 1558 he published a text aimed at Queen Mary, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women. By the end of the year, however, his misogyny backfired: Elizabeth found the work deeply offensive, and Knox would never again be welcome in England.

Instead he wound up back home in Scotland. While England was developing a church actively led by bishops, with worship that left Reformed Protestants elsewhere unimpressed and whose center was the anointed monarch, further north in Scotland in 1559 Reformed Protestant energy exploded.

Within a year after Knox returned, the Scots parliament engineered an aggressively Reformed church called the “Scots Kirk” and outmaneuvered the politically inept Mary Stuart, queen of Scotland and a Catholic deeply wedded to foreign French politics. In 1567 she fled to England (only to be imprisoned by her cousin Elizabeth), and Scots Calvinists ruled in the name of her son, James VI.

Men like Knox and Andrew Melville (1545–1622), deeply enamored with continental Reformed churches, in some ways outpaced them. In 1561 the Scots Kirk abolished the “nonbiblical” feast of Christmas—a holiday still observed by mainland Protestants, even in Zurich. And while Calvin himself never formally elevated discipline as one of the marks of a true church, the Scots Kirk surely did.

The Lord’s Supper was celebrated sitting at a table, like the Last Supper, and psalm-singing became the only accepted form of sacred music. The nation itself was organized on Presbyterian lines, and from 1562 used the Book of Common Order (also known as Knox’s Liturgy). Scotland became a thorough-going Reformed territory. The Church of England in the same period was a tricky animal: it was in constant conversation with other Reformed churches of Europe, but England’s Reformed cousins continued to be disappointed that it would not catch up.

John Jewel, new bishop of Salisbury in the early 1560s, engaged in a flurry of tracts with English Roman Catholic Stephen Harding. In one, Apology for the Church of England (1562), Jewel grounded himself in Scripture and the early church fathers to defend not simply sola fide (i.e.: “faith alone”) Protestantism, but the authenticity and legitimacy of the English church.

As 1600 approached, three events strengthened this official English church. The destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588 (preventing an attack on England) was widely construed as divine approval of the Elizabethan church. Archbishop John Whitgift finally humiliated and jailed his long-time Puritan antagonist, Thomas Cartwright, suppressing opposition. And a young cleric named Richard Hooker wrote his famous eight-volume Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, agreeing with the earlier Jewel that the established English church is legitimate, and one ought to accept her ways of life and prayer.

All glory, Laud, and honor

Even while the Scots continued on their Presbyterian course, James VI of Scotland (1566–1625) became James I of England in 1603. Toward the end of his reign in the 1620s, a group of clergy began to preach and write about the holiness of church buildings and the authority of clergy; in some places they even reconstructed altars. They achieved positions of great influence in the reign of James’s son, Charles I (1625–1649), and came to be known as Laudians, after Charles’s archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud.

The Laudians worked in earnest to distance the Church of England from its Reformed connections by emphasizing the very rites and ceremonies that had long annoyed Puritans, and even began innovating new-but-old rituals: celebrating church consecrations (no rite existed for this in the prayer book), building rails around the Communion table, and adopting long-discarded vestments.

In returning ceremony and clerical rank to the church, the Laudians created the narrative that Elizabeth had fashioned a middle-way church that was not Reformed and that could claim certain continuities with the pre-Reformation church, albeit without the pope. As a result of their efforts, the average member of the Church of England began at last to perceive it as distinct from Reformed Protestantism. The English church’s validity was sealed with a new name: Anglicanism.

Charles I was executed in January 1649 by Parliament as part of the disastrous English Civil War; after the government of Oliver Cromwell in the 1650s, Charles’s son (1630–1685) was invited back to take the throne as King Charles II in 1660. The “Cavaliers” who had supported Charles’s father were uncompromising, and their Laudian vision—better put, their Anglican vision—for the established church was crystal clear.

So was the Church of England “confessional”? The answer is a cautious yes and a cautious no. The 39 Articles, the Homilies, and the Book of Common Prayer confessed a Reformed faith. But English worship life left the door open just a crack to allow an exit from the international communion of Reformed churches. The Laudians of the seventeenth century widened that crack, forming Anglicanism, a tradition that still stresses an aesthetic, sacramental piety and that has an ambiguous relationship with both Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. This is hardly a tidy via media, a Catholic church independent of Rome. But neither is it simply Reformed Protestantism with bishops. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Calvin Lane

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Calvin Lane is affiliate professor at Nashotah House Theological Seminary and associate rector of St. George’s Episcopal Church, Dayton, Ohio. He is the author of The Laudians and the Elizabethan Church and the forthcoming Spirituality and Reform, c. 1000–c. 1800.Next articles

The king, the emperor, and the theologians

The men who promoted and disputed reform in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Spain

David C. Steinmetz, Paul Thigpen, and the editorsCalvin, councils, and confessions: Recommended resources

Where can you go to learn more about Calvin, the Reformed faith, and the development of the Reformation? Here are some recommendations from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors

The EditorsChristian History & Biography Celebrates 25 Years

We need history to inform our lives

Jennifer TraftonBenedict, Did You Know

Interesting and little-known facts about Benedictine monasticism.

The EditorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate