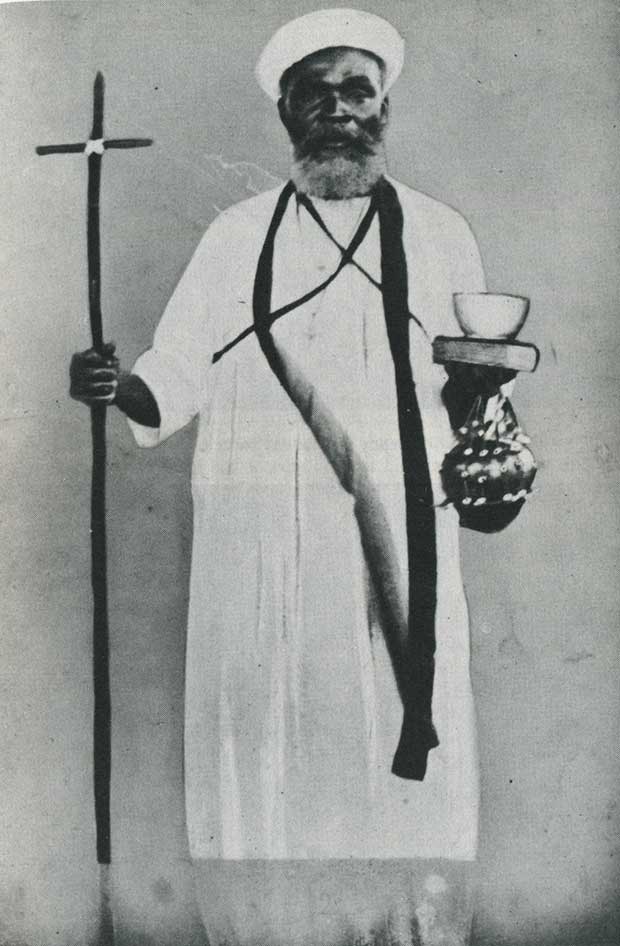

WILLIAM WADE HARRIS, AN AFRICAN FOR AFRICANS

[Above: William Wade Harris in 1914—public domain because photographed before 1925]

IN 1909 colonial authorities imprisoned as a traitor William Wadé Harris, an African Christian educator. Harris was from the Grebo tribe, who were being displaced and ruled by liberated slaves from the United States. Desirous of British rule, he had defaced the Liberian flag and raised a Union Jack.

Harris was about forty-five years old when jailed. As a boy he had learned to read English and Grebo in a Methodist school. Having accepted Christianity, he was baptized at the Methodist mission in Sinoe when he was in his early twenties. After stints as a crew member on coastal voyages and employment as a mason, he became an Episcopalian and taught in an Episcopal school. He also worked as a government translator and saw himself as a spokesman for the Grebos.

That was the situation Harris was in when he was imprisoned. In prison for at least a year, he rethought his purpose. He emerged claiming a vision in which the angel Gabriel commanded him to preach. His efforts in Liberia bore little fruit. Had he remained there, he would be unknown. Instead, he walked south and is now internationally recognized as an effective if eccentric evangelist.

On this day, 27 July 1913, William Wadé Harris set out to evangelize the French colony of the Ivory Coast. Working there for a little over a year, he baptized between 100,000 and 120,000 Africans after they burned their fetishes. He also had great success in the Gold Coast [Ghana].

For decades missionaries and governments had tried to persuade west coast Africans to abandon their fetishes. Few would. One reason was the missionaries would not baptize converts until they had gone through months of catechism and proven their sincerity by life changes. To Africans, this meant they were unprotected from evil spirits once they rid themselves of their fetishes. Harris baptized immediately when an African burned his or her fetishes. Sensibly he put chiefs in charge of the new Christians so that tribal command structures remained intact.

His message was simple: burn fetishes; cease from witchcraft; be baptized in the name of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; be clean; work; and pray to the creator God. He set Christian words to native tunes. And he urged his converts to join either the Methodist or Catholic churches that worked in the region; many did and church membership swelled by thousands. Other Africans did not want to be under white authority and chose instead to form their own churches. They waited ten years or more for teachers that Harris promised, tens of thousands remaining faithful to the little knowledge they had. Harris’s churches account for hundreds of thousands of believers today.

Harris was successful because he drove out demons and offered a new paradigm that made moderate demands on a people caught in flux between their old world and Christianized civilizations. Many accounts testify that Harris prophesied events that soon came to pass (at least partially). For example, one man swore he had not hidden a fetish, although bystanders insisted he had. Harris baptized him with a warning he would die if he was lying. Within a couple hours the man dropped dead in full view of those who had heard the warning. Such incidents—and there were many—created an aura of respect for the power of God. Harris endorsed a number of disciples who were almost as successful as himself.

On the personal side, however, Harris acquired many women, some of whom accompanied him on his mission trips. His prophecies about coming world events (in which he expected to feature largely) failed dismally, raising questions about the source of his message.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more accounts of Africans taking the gospel to Africans, consult Christian History #79, African Apostles: Black Evangelists in Africa