LITTLE IS KNOWN OF MARTIN OF MAINZ, BURNED THIS DAY

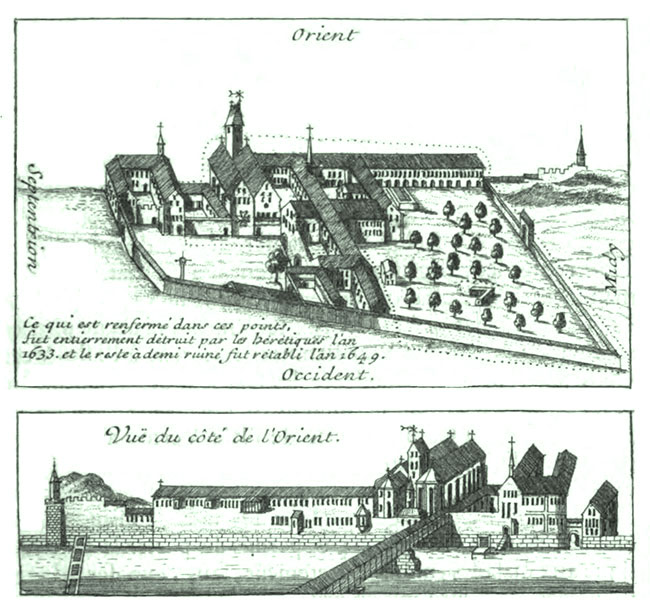

[Above: The Green Isle of Strasbourg (Merswin’s Island)—unknown engraver, public domain]

WHEN WE PASS through thick fog, we see the outlines of the objects closest to our path, but farther off things are more indistinct and mysterious. Beyond a certain point nothing is visible. History is similar.

Toward the end of the fourteenth century, a group known as “friends of God” operated in Germany. Little can be discovered about them in the fog of history. They took their name from John 15:15: “No longer do I call you servants, for the servant doesn't know what his lord does. But I have called you friends, for everything that I heard from my Father, I have made known to you.” They found inspiration in Nicholas of Basel. Longing for direct communication with God, Nicholas had severely punished his body and renounced the woman he had planned to betroth. Eventually, however, he decided that inward self-denial was more valuable than outward affliction of the body.

He must have been persuasive. Men from Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, and Italy joined him. They planned to preach repentance “to the five ends of the earth” if the world’s spiritual condition did not improve. Even the famous mystic Johannes Tauler gave serious attention to Nicholas. So did Rulman Merswin, a merchant whom Nicholas convinced to purchase an abandoned monastery on an island as a spiritual retreat. Merswin bought the island, but the project failed after his death. Merswin also reproduced some teachings of a “friend of God from the highlands,” although some scholars consider this a fictional cloak for his own writings.

Out of the movement came the anonymous Theologica Germanica, a famous tract that called for mystical, godly living. Persecutions came, too. Nicholas converted a lawyer and a Jew. When authorities in France, burned him as a heretic, sometime after 1393, the lawyer and Jew burned with him. Heidelberg burned some of his other friends around the same time.

One of Nicholas’s converts was a Benedictine monk named Martin of Mainz (Mayence). Martin also died for his faith, charged with sixteen heresies. Some of these were statements of biblical truth that challenged the prerogatives of the established church. For instance, he refused to abide by set hours of prayer and saints’ days. He claimed all Christians are priests, rejected rote repetition of the Lord’s Prayer, and denied the efficacy of outward works for salvation. He claimed that Christ on the cross suffered more from God’s judgment than from the physical torture.

Other charges, if not merely the accusers’ reductio ad absurdum of Martin's views, were more serious. His enemies said he elevated Nicholas’s teachings higher than those of St. Paul, claimed that Nicholas was perfect, and said that Nicholas could rightly command murder or fornication. They accused him of teaching that the perfect man need not pray to God for liberation from infirmities or to pray that God “lead us not into temptation.”

On this day, 19 July 1393, authorities in Cologne burned Martin of Mainz to death as a heretic. Apart from that event and the sixteen charges leveled against him, his life is shrouded by the fog of lost documents and the thick veil of years.

--Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more about Christians in the Middle Ages, consult Christian History #127, Medieval Lay Mystics