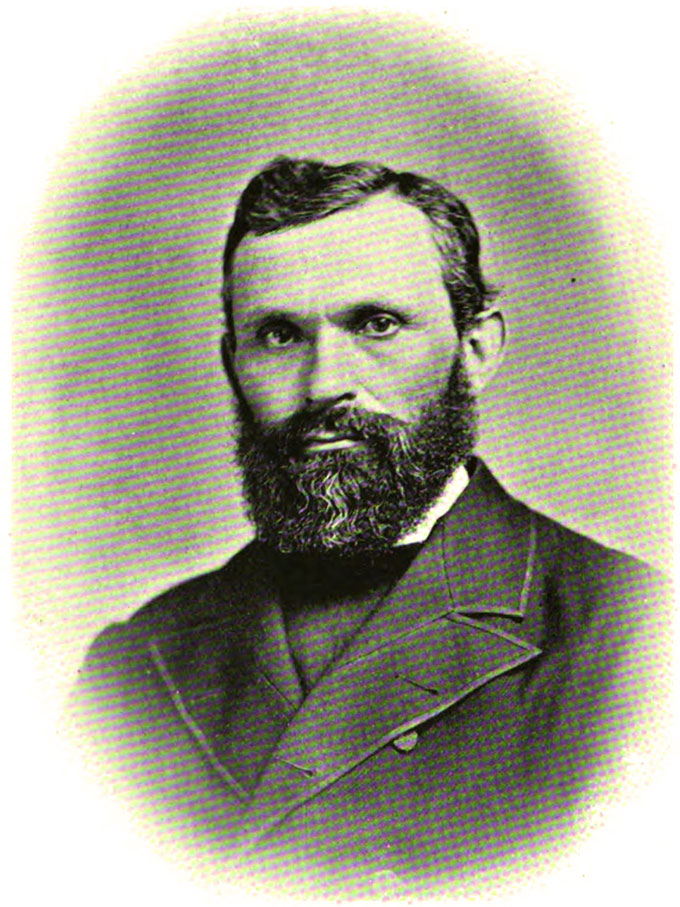

SAMUEL SCHERESCHEWSKY'S UNUSUAL PATH TO PREEMINENCE

[Above: Samuel Schereschewsky—William Stevens Perry. The Bishops of the American Church, Past and Present. Christian literature Company, 1897. public domain.]

ON THIS DAY, 31 OCTOBER 1877, Samuel Schereschewsky was consecrated Bishop of Shanghai in Grace Church, New York. His path to a see in the Episcopal Church is among the most unusual ecclesiastical stories of the nineteenth century.

A Lithuanian Jew, Schereschewsky showed immense intellectual and linguistic abilities. A half-brother, who reared him following the death of his parents, had the means to educate him in the best schools of Europe. He was well on his way to becoming a rabbi when someone placed a Gospel in his hands. Reading it, he accepted the premise that Jesus was the Messiah. Yet his conviction did not move him to follow Christ.

Discussions with Christian missionaries brought him closer to a genuine conversion. He migrated to the United States, and there, under the evangelism of the Rev. John Neander, a Christian Jew, he finally committed to Christ.

His Christian friends were Presbyterians and he became one, too. Schereschewsky sensed a call to Christian work and enrolled in Western Theological Seminary, supported in part by a Presbyterian scholarship. However, increasing doubts about Calvinist doctrine led him to withdraw from the school. For a second time he had failed the expectations of benefactors.

Schereschewsky now migrated to the Episcopal Church and entered one of its seminaries. Responding to an appeal by Bishop William J. Boone, he offered himself for mission work in China and sailed in 1859 with a handful of other men. Because civil disturbances were raging in China, the new missionaries devoted their early months in China studying Chinese rather than in ministry.

Within a year, Schereschewsky was able to translate into Mandarin. Translation would be his forte. As part of a committee, he translated the Old Testament into Mandarin, and, with a colleague, the Book of Common Prayer. To help Chinese readers, his Bible included notes, especially to explain the meanings of personal names and place names. His translation was not literal but thought-for-thought. Not only did he try to convey the sense through Chinese idioms but he sought similar-sounding Chinese words to replace names.

Finances were often short. At such times, the mission permitted him to work as an interpreter for Western powers, gaining even more proficiency in the language.

In 1868, he walked seven hundred miles to meet Susan Mary Waring, having heard she was single. Within two weeks of meeting each other, they announced their engagement. With her sunny disposition, work ethic, and loyalty, she became an invaluable worker in the mission. James Arthur Muller wrote,

Mrs. Schereschewsky admitted that her patience was sometimes tried by his ability so to concentrate on his translating that he would hear or see nothing else. He would suffer no interruption, no matter how urgent she thought the occasion for it to be. And it was always a task to get him to bed.

When asked to become bishop, Schereschewsky refused. He considered himself unqualified. Fellow missionaries agreed he did not have the temperament for the job. But the board insisted and, reluctantly, Schereschewsky acceded. “May He who is the Strength of the weak and the Guide of the perplexed be my Strength and my Guide in this very solemn matter.”

A strong believer in higher education, Schereschewsky had declared that schooling would be his priority should he become bishop of Shanghai. When the board balked at the cost of a school, he promptly threatened to resign. He got both the authorization and the funding for the college that became St. John’s University. Believing that the Chinese church must develop its own leadership, he expanded the role of Chinese catechists and priests.

His tenure as bishop was fairly short. Overcome by heat and overwork, he suffered a brain lesion and developed Parkinson-like symptoms in his body (although his linguistic abilities were unimpaired). He visited Europe and the United States hoping for a cure. Unable to find one, he resigned his see in 1883.

Although wheelchair bound, he returned to China to continue translation. He was able to do so only because of the heroic support of Susan and the assistance of Chinese workers. Although he could get irritable, all agreed he put the best face on his suffering and limitations. For years he was reduced to typing with a single finger and did two thousand pages that way for his Wen-Li Bible, which the Chinese called “the one-finger Bible.” Wen-Li is a classical Chinese dialect, suited for educated audiences and university students. Schereschewsky also revised his earlier translations. In addition to them, he translated the Gospels into Mongolian and prepared grammars and dictionaries. Near the end of his life, he told a coworker,

I have sat in this chair for over twenty years.

It seemed very hard at first.

But God knew best.

He kept me for the work for which I am best fitted.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more on the Christianity Schereschewsky helped establish in China, consult Christian History #98, How the Church in China Survived and Thrived in the 20th Century