HOW JOHN HENRY NEWMAN BECAME ONE OF ENGLAND’S MOST FAMOUS CATHOLICS

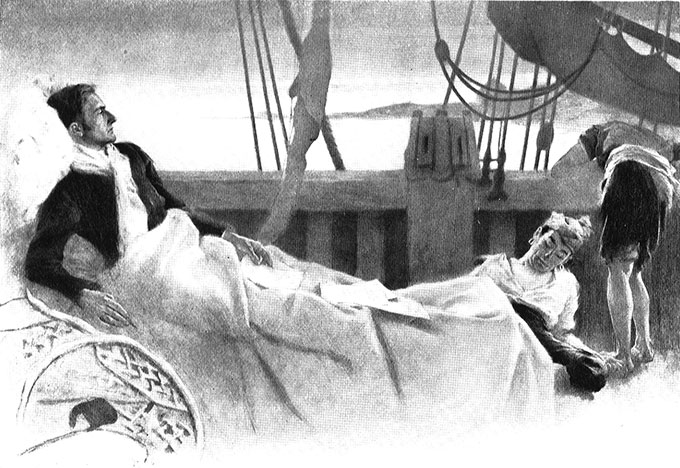

[Above: John Henry Newman, ill and becalmed at sea pens "Lead Kindly Light."—Allan Sutherland. Famous Hymns of the World, Their Origin and Their Romance. New York, Frederick A. Stokes, 1906. public domain]

LEAVING HIS TRAVELING COMPANIONS in Italy, John Henry Newman, a Church of England vicar, headed home by way of Sicily. However, he became ill while on the Mediterranean island. Out of his head with fever, he told his servant, “I shall not die, for I have not sinned against the light.” When his condition improved enough to travel again, he declared he had a work to do in England, although just what it was he did not know.

Weeks passed but he was stuck on Sicily owing to his weakness and the unavailability of a ship. He ached to get home. When finally he was again at sea, he was becalmed for a week in the Strait of Bonifacio (between Sardinia and Corsica).

There, on this day 16 June 1833, he drafted his famous hymn, “Lead Kindly Light.”

Lead, Kindly Light, amid the encircling gloom,

Lead Thou me on;

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead Thou me on.

Keep Thou my feet;

I do not ask to see the distant scene;

one step enough for me.

Following more delays, he made it home. His task became clearer on his first Sunday back at Oxford. On 14 July, John Keble preached the sermon “National Apostasy.” This electrified Newman and brought into being The Oxford Movement.

At the time the British government declared that it had absolute authority over the church. Newman threw himself into countering this claim. He edited Tracts for the Times, publications that sought to define the ground of the church’s authority and doctrines to free them from political whims.

Over the next decade, Newman’s studies of early theological disputes and the writings of church fathers drew him toward Roman Catholicism. If the Church of England had legitimate authority at all, he argued, it was as a branch of the universal visible church. “I ever kept before me that there was something greater than the Established Church, and that that was the Church Catholic and Apostolic, set up from the beginning, of which she was but the local presence and the organ. She was nothing, unless she was this.”

Had he been an evangelical, he might have defined the church as the invisible body of all genuine Christians connected by faith to Christ. However, he “thought little of the Evangelicals as a class. I thought they played into the hands of the Liberals.” They “had no intellectual basis; no internal idea, no principle of unity, no theology,” and, “at no time [have] been conspicuous, as a party, for talent or learning.”

In order to remain with the Church of England, he needed to show that its doctrine was faithful to the doctrine of the larger church. In Tract 90 (1841), he interpreted the Thirty-Nine Articles (the Church of England’s fundamental teachings) in light of Roman Catholic doctrine. This created such a furor that Newman resigned positions and moved to his retreat at Littlemore.

A key Protestant objection against Roman Catholicism was that its dogmas had changed since the apostolic age. Newman himself had made this argument. Until he could satisfy his conscience on this score, he remained with the Church of England. He studied the development of doctrine and concluded it could evolve. His last barrier to submitting to Rome was gone. In 1845 he joined the Catholic Church.

After he became a Catholic, he penned two notable books. The first was The Idea of a University (1852) prompted by his role developing a Roman Catholic college in Ireland. The second was a long-winded self-defense when Anglican author Charles Kingsley accused him of lying. In Apologia pro Vita Sua (A Defense of His Life, 1864), Newman explained how the light of reason and of conscience led him to leave the Church of England.

For many years, Catholics were suspicious of Newman. He had, after all, written against them in the past. He spent decades overcoming prejudice, but in 1879 Pope Leo XIII made him a cardinal.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

For more about Newman and the tractarians, read "Christ in his church: Newman and the Tractarians" in Christian History #9, Heritage of Freedom: Dissenters, Reformers, and Pioneers