Booth and Mumford Partnered for the Gospel

Composite image of William and Catherine.

THE FIRST TIME that William Booth and Catherine Mumford met, she scolded him when he confessed he sometimes drank a little port. As a complete abstainer and the daughter of an alcoholic, she would not allow even health as an excuse for imbibing alcohol. Soon they met again at a tea meeting of Methodist Reformers, where she was deeply moved by the message he preached. When she became ill, he escorted her home across London. “Before we reached my home we both felt as though we had been made for each other,” wrote Catherine. William pronounced it love at first sight. On this day, 16 June 1855 they married, becoming one of the greatest husband-wife evangelistic teams known to history, and the founders of the Salvation Army.

From his teen years, Booth had worked to present the Gospel and deliver souls from the bondage of sin. The Wesleyan Methodist church he attended wanted nothing to do with people who deposited lice on the pews—exactly the people Booth hoped to reach. Suspecting him of being a “reformer” (a group which called for evangelization of the poor and outcast), the Wesleyans even took away his membership. Eventually Booth switched his allegiance to the Methodist New Connexion and preached throughout the English countryside.

Mumford also was a soul winner. A feminist, she took sharp exception when Booth spoke of women as the weaker sex. She claimed women had the right to preach. Booth disagreed a first, but said he would not stop her. Seeing the fruits of her ministry, he went further and endorsed women preachers. As a result, when they founded the Salvation Army, he allowed women to preach and to serve in leadership roles.

Soon, William and Catherine realized that they had to meet more than spiritual needs. Starvation, sickness, and poverty were pervasive. They established schools, taught women to sew, opened food kitchens and found employment for the needy—and met furious opposition from tavern keepers and pimps who saw trade drop off when clients were converted.

Some pastors also resisted the Salvation Army, denouncing its evangelistic meetings as circus-like and too brash. As Booth held tent meetings and got attention with brass bands, detractors hurled bricks and bottles at the evangelists. Salvation Army workers died in mob attacks, but the Booths and their co-workers persevered and the Salvation Army spread worldwide.

Catherine died of cancer in 1890. Her last words were, “The waters are rising, but so am I. I am not going under but over. Do not be concerned about dying; go on living well, the dying will be right.” William lived until 1912 and carried on his work almost to the end. All but one of the Booths’ nine children survived to adulthood. Several became vibrant Christian workers in their turn.

—Dan Graves

----- ------ ------

Maud and Ballington Booth got the inspiration for their ministry from the Salvation Army, founded by Maud's father-in-law. That work is described in Boundless Salvation: William Booth and the Salvation Army. Watch it and Our People: The Story Of William and Catherine Booth at RedeemTV.

(Boundless Salvation and Our People can be purchased at Vision Video.)

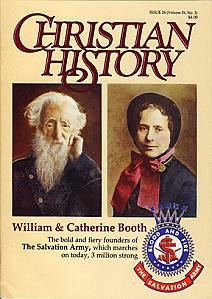

For more about the Booths, read Christian History #26, William and Catherine Booth