CARDINAL NICHOLAS OF CUSA WAS BRILLIANT, MYSTICAL, AND FLAWED

[Nicholas Cusanus—Wikimedia]

ON THIS DAY, 21 SEPTEMBER 1451, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa ordered Jews of Arnhem (in the Eastern Netherlands) to register at the office of the burgomaster (magistrate) and wear a yellow badge. He forbade them to engage in usury or to loan money to Christians. His instructions came in a sermon on absolution. No Christian could receive absolution who permitted a usury-practicing Jew to live beside or below him. His rules enforced, and even exceeded, laws that originated in previous centuries, including a canon (church law) of the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) that had required Jews and Muslims to wear distinctive dress. At the same time, Cusa sternly forbade anyone to injure a Jew night or day, openly or by stealth.

Cusa, as papal legate, had issued similar instructions throughout Germany that same year. His aim was not only to end moneylending for interest but also to prevent intermarriage between Jews and Christians. Pope Nicholas V, however, did not stand by his legate’s actions, rescinding some of his decrees.

From his decrees about Jews, one might assume Cusa was a closed-minded bigot. Actually he was a peacemaker, reformer, and thinker with wide interests. Two years after issuing his orders requiring badges, he authored De Pace Fidei (On the Peace of Faith) which sought common ground between Christians, Jews, and Muslims—although the two non-Christian faiths found it unacceptable because it insisted on Trinitarian doctrine.

Born in the first year of the fifteenth century, Nicholas of Cusa became the greatest German thinker of his generation. He stepped outside the scholastic mold of his predecessors, writing many innovative books of theology, mysticism, mathematics, science, and philosophy. He suggested an experiment to prove air has weight. He demonstrated that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery. That document pretended to give the Lateran Palace and other lavish gifts to the pope and had often been invoked to support papal claims of lordship over central Italy.

Ever a peace-seeker, Cusa was among those who sought to reconcile the eastern and western branches of Christianity. He tried to bring the papacy into agreement with the Council of Basel. Like his attempts to bring the monotheistic religions into mutual tolerance, his efforts to reconcile divisions in Christianity failed. As a reformer, however, he touched many raw nerves. While bishop of Brixen, he even found himself imprisoned when Duke Sigmund of Tyrol attempted to force concessions from the church. The pope excommunicated Sigmund, but Cusa left Brixen, never to return.

Cusa’s reforms did not persist, but his mystical speculations arrived at interesting conclusions that came into their own in later centuries. For instance, he taught that the universe must be curved: “The fabric of the world will as it were have its center everywhere and circumference nowhere, because the circumference and the center are God who is everywhere and nowhere.” Motion is not absolute but is relative to the beholder, he said, anticipating a similar, but mathematically more rigorous concept by Einstein. He correctly taught that earth spins on its axis. He advocated the application of mathematical quantification to all science; God created all things in “number, weight, and measure.” He avoided absurdities by finding reconciliation of the finite and infinite in the mystery of Christ. “Every lover dwells in love,” he wrote, “and all that love the truth dwell in Christ....[N]one knows the truth unless the spirit of Christ be in him.”

Nicholas endowed an old men’s home in Cues, his birthplace. Its library preserved many of his works so that his thought was not lost following his death in 1464.

—Dan Graves

----- ----- -----

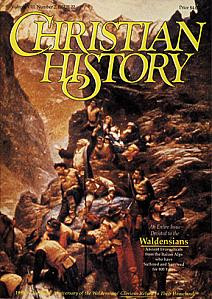

Read more about Cusa in "The Donation of Constantine" in Christian History #22, Waldensians: Ancient “Evangelicals” from the Italian Alps

Never miss an issue of Christian History. Subscribe now.