Benedict, Did You Know

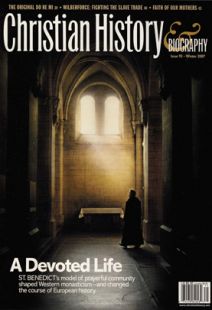

A living tradition

Today there are about 25,000 Benedictine monks and nuns, as well as over 5,000 Cistercians and others who live according to the Rule of St. Benedict. In the last 40 years, these numbers have been declining, but the number of “oblates,” lay people associated with monasteries, is growing rapidly and now exceeds the number of monks and nuns. Many of them are Protestants.

—contributed by Hugh Feiss, OSB

Walking in Benedict’s steps today

Visit Clear Creek Monastery in Oklahoma and you will see something as close to 12th-century Benedictine monastic life as can be found in the 21st century. It all began in 1972 when a group of University of Kansas students discovered Fontgombault, a traditional Benedictine monastery in France known for its Gregorian chant, traditional Latin liturgy, and strict adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict. Around 30 students stayed at the abbey as guests, and a handful never left. The abbot of Fontgombault called it the “American Invasion.”

Now Fontgombault has come to America. The students-turned-monks returned to the U.S. in the 1990s and founded Clear Creek Monastery. There, they continue to pursue a traditional Benedictine lifestyle.

Talk to the hand

Benedict encouraged his monks to be silent as often as possible. But of course, some form of communication is necessary in order for people to live together. In the Year 1000, Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger describe a Benedictine sign language manual from Canterbury listing no less than 127 hand signals, including signs for various people in the monastery, ordinary objects such as a pillow (“Stroke the sign of a feather inside your left hand”), and requests such as “Pass the salt” (“Stroke your hands with your three fingers together, as if you were salting something”).

“One gets the impression,” write Lacey and Danzinger, “that mealtimes in a Benedictine refectory were rather like a gathering of baseball coaches, all furiously beckoning, squeezing their ear lobes, meaningfully rubbing their fingers up and down the sides of their noses, and smoothing their hands over their stomachs.”

If you build it, they will pray

One of the greatest treasures from the era of Charlemagne that survives today is the Plan of St. Gall. This architectural drawing (reconstructed here) depicts a Benedictine monastery perfectly suited to the monastic life of prayer, study, and work. The monastery was never built, for reasons that are a mystery to us. But scholars believe the plan was developed in the ninth century as an example of the ideal monastery. A copy survives because Abbot Gozbert (816–837) requested it to guide his building program at the monastery of St. Gall and preserved it in the library there.

The plan tells us a lot about medieval monastic life, including the fact that in the ninth century a monastery

was meant to be self-sustaining—almost a mini-village in itself, complete with vegetable and herb gardens, granary, livestock, medical facilities, library, laundry, craft workshops, and guest lodging.

The first capitalists?

Benedict emphasized the role of manual labor as a God-given part of human life and instructed his monks to spend appropriate amounts of time each day in work, prayer, and reading. According to a long-standing thesis, Benedictine monks changed the West’s view of work from being looked down upon to being respected as a form of prayer—leading, in turn, to the rise of capitalism. This argument has its flaws. It is true, however, that Benedictines were very good at “estate management,” and that they helped to teach others the value of a regular, disciplined working life.

—contributed by Glenn W. Olsen

Hops and hospitality

Before she became the reformer Martin Luther’s wife, Katharinevon Bora was in the beer-brewing business—as a Benedictine nun. Yes, Benedictines were once famous for their beer. In the Middle Ages, beer was a staple for most people. Monks in particular needed the nutritional benefits of beer because of the fasting they did. So in the seventh and eighth centuries, they began brewing their own and eventually developed advanced methods of beer-making. A brewery required up to 100 monk workers.

Combine Benedictine beer with Benedictine hospitality and you get pubs! Important guests were given celia, made from hops (a type of flower) and barley, and pilgrims drank cervisa, made of wheat, oats, and hops. Some Benedictine monasteries are still brewing—the German beer Andechs, for instance. But we mustn’t forget what St. Benedict said about drinking: “Let us at least agree to drink sparingly, and not to satiety.”

Plants and potions

Mystery writer Ellis Peter’s famous detective, Brother Cadfael, is a medieval Benedictine monk who is also an herbalist—the forerunner of the pharmacist. In the Middle Ages, every good monastery had herbalist monks who treated the sick by concocting medicines from plants, herbs, and minerals. No doubt some of these were more effective than others, but aloe, rhubarb, and dandelion were a few popular ingredients still used medicinally today. More recently in the alternative medicine movement, the medical and botanical treatises of 12th-century Benedictine nun Hildegard of Bingen are making a comeback—but aspiring herbalists may have a hard time finding a unicorn’s horn.

Holier than thou?

To those who thought celibate monks and nuns had a spiritual leg up on ordinary folks and a more direct route to heaven, 12th-century monk-bishop Hugh of Lincoln had a ready answer: All Christians—even married laypeople—are called to be saints, exhibiting love, truthfulness, and chastity. “The kingdom of God is not confined only to monks, hermits and anchorites,” he said. “When, at the last, the Lord shall judge every individual, he will not hold it against him that he has not been a hermit or a monk, but will reject each of the damned because he had not been a real Christian.”

Heretics

Heretics often provided a great service to the church. For example, Marcion rejected the Old Testament and the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and John, thus forcing the church to define the New Testament canon. Arius, in denying the deity of Christ, made the church articulate the doctrine that became most crucial to Christianity.

—contributed by Tony Lane

A tragic split

In 451 the Council of Chalcedon proclaimed that Christ is one person with two natures—fully God and fully man—and condemned the view of Eutyches who taught that Christ has only a divine nature.

Five eastern churches—Armenian, Coptic, Syrian, Ethiopian, and Indian Malabar—disagreed with both the council’s decision and with Eutyches’ teachings. These “Oriental” or “non-Chalcedonian” churches held that the incarnate Christ is “one Nature out of two.” They eventually separated from the rest of the church. More recently, however, the Oriental Orthodox are taking steps to reconcile with the Chalcedonian churches (Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox) and the two sides are discovering that their beliefs about Christ are much closer than they realized.

India’s apostle

Indian Christians claim an ancient heritage. According to tradition, the Apostle Thomas landed on the Malabar coast of southwest India in A.D. 52. He converted people from various castes, and finally died in Mylapore (now within the huge city of Madras, recently renamed Chennai) at the hands of hostile Brahmans. The second-century Acts of Thomas relates that Thomas encountered an Indian official named Abban in Jerusalem, who invited him to come to India to build a place for King Gundaphorus. Thomas agreed to go with Abban, and the king eventually became a Christian.

“Uncle John”

As a boy, the great parliamentarian and abolitionist William Wilberforce loved to visit the pastor John Newton to hear his stories and songs. When Wilberforce later returned to his childhood faith, he also turned to his childhood friend as a spiritual mentor.

Antislavery

William Wilberforce and his fellow abolitionists engaged in an antislavery public opinion campaign unprecedented in English history. In 1814 they gathered one million signatures, one-tenth of the population, on 800 petitions, which they delivered to the House of Commons.

By The Editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #93 in 2007]

Next articles

The Tale of Peter Abbot

One of Cluny's most “venerable” leaders believed firmly that the church is always in need of reform.

Garry CritesLiving like a monk in the “real world”

Count Gerald of Aurillac took the values of the monastery into the realm of everyday life—and the battlefield.

Dennis MartinBenedict, a devoted life: Recommended Resources

Dig deeper into this issue's theme

The authors and editorsChristian History Timeline: Benedict and the Rise of Western Monasticism

From its roots in the early Eastern church, through the Benedictine centuries, to the birth of new kinds of religious orders in the Middle Ages

compiled by Antonia Ryan with contributions from Carmen Acevedo ButcherSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate