Restless and reforming

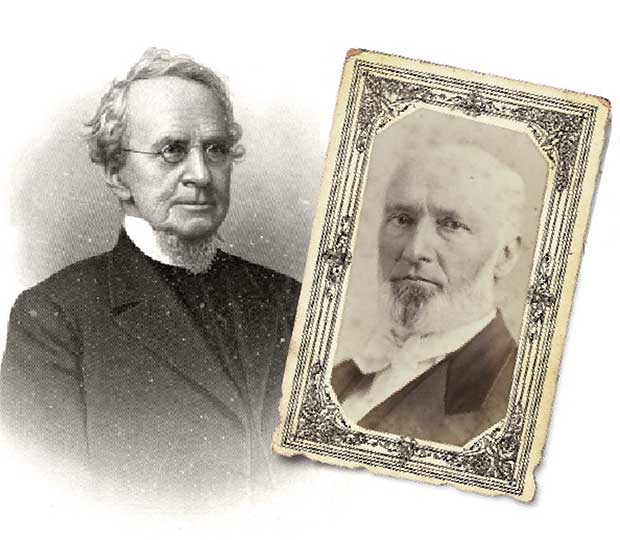

[John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff]

WHAT DOES IT MEAN to be a Reformed Protestant in the United States? A certain flower probably comes to mind—namely Calvinism’s five points of TULIP fame: total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints. Today many people first meet Reformed Protestantism through the “New Calvinism” made popular by organizations like the Gospel Coalition, pastors like John Piper and Tim Keller, and movements like the YRR (“young, restless, and Reformed”), all of whom emphasize a clarity on these doctrinal points as a counter to creeping modernism in the church.

However many confessional Reformed Protestant communions feel that TULIP’s five points—a bumper sticker rendition of the 1619 Synod of Dort’s major declarations—fail to capture the depth and subtlety of what it means to be Reformed. In its zeal to recover the Reformation, New Calvinism has been criticized for stressing Dort’s declarative doctrines over the way that, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Reformed churches practiced pastoral ministry and worship. Indeed when Reformed churches created a separate identity from Lutherans and Anglicans, they originally understood that Christianity involved much more than doctrines of original sin, justification by faith, or predestination. And if twenty-first-century Reformed churches in the United States have trouble differentiating themselves from the New Calvinism as they attempt to retrieve the past, that challenge actually first surfaced during the middle decades of the nineteenth century.

The benevolent empire

During Charles Finney’s (1792–1875) famous revivals, a cooperative spirit arose that prompted a series of voluntary associations—everything from Sunday school and Bible societies to temperance and antislavery organizations. These movements blended Protestantism with the spirit and demands of the new nation in ways that made the church of the Reformation look odd and impractical.

The Benevolent Empire—as the movement was called—now sought to make new converts through a modified Calvinism taught by those like Nathaniel Taylor at Yale Divinity School. Many felt this smoothed hard edges of the faith away in the service of evangelizing the new nation.

The cooperative and pragmatic Protestantism of Finney, Taylor, and others also wedded Christianity to the spread of Western civilization. They and other East Coast Protestants fully expected to take the faith (and its supporting institutions) to the frontier (and to foreign lands through missionaries) and so establish a Christian society.

Ethnic Protestants—especially Dutch and German immigrants—resisted. They tried to maintain Old World traditions and institutions even as church members assimilated as Americans. Many of these “hyphenated” Protestants held on to the confessions, church polities, and liturgies of Europe’s Protestant establishment.

Some Presbyterians of Scottish and Irish heritage, called “Old School” and already at home in North America for a century or so, resisted the Benevolent Empire in hopes of maintaining the teaching and practice of the Westminster Confession and Catechisms. German Reformed, Dutch Reformed, and Old School Presbyterians, along with Lutherans, all represented an alternative to the evangelical Protestant mainstream that began to coalesce during the two decades before the Civil War.

Princeton Seminary’s Charles Hodge (1797–1898) and Benjamin Warfield (1851–1921) presented to the wider world an Old School Presbyterian defense of the convictions shaping the Westminster Confession. Some time later the Dutch American Calvinist tradition, centered around Calvin College, would produce scholars such as Nicholas Wolterstorff (b. 1932), Alvin Plantinga (b. 1932), and Richard Mouw (b. 1940)—all part of evangelical intellectual life since the 1970s. But fewer people are aware of the German Reformed tradition or the significant arguments in favor of church tradition made by John Williamson Nevin (1803–1886) and Philip Schaff (1819–1893).

German Reformed Protestantism took its cues from German-speaking Calvinists centered in the city of Heidelberg. As a consequence of religious wars in Europe and economic opportunity in North America, Swiss and German Protestants had begun in the 1700s to settle in Pennsylvania, a haven of both religious freedom and fertile soil. By the 1820s a small immigrant and rural church began to organize around denominational structures and schools. Mercersburg Seminary, founded in 1825, was the German Reformed Church’s institution for training pastors. Its leaders managed a coup in 1840 when they lured Nevin, a Scotch-Irishman and native of Pennsylvania, to leave Western Theological Seminary (now Pittsburgh Seminary) and the Presbyterian Church to teach theology and lead Mercersburg Seminary.

Abandoning the anxious bench

Part of what made Mercersburg appealing to Nevin was his own reading in contemporary German theology and philosophy, but he also had a growing dissatisfaction with what was happening to Anglo-American Protestantism. In 1843 he wrote The Anxious Bench, one of the most searching theological and psychological critiques of revivalism ever produced in the United States.

The critique directly attacked one of Finney’s most novel techniques: bringing potential converts to a bench at the front of the church to be prayed over (the origin of today’s altar call). Nevin accused Finney of abandoning the rhythms and ministry of historic Protestantism, writing at one point:

We are all more or less familiar with Christianity in this form. It has no faith in the Church as a Christian mystery, and shrinks from the acknowledgment of any saving virtue in Christ’s Sacraments. It is of course constitutionally unliturgical; as it can see no meaning in the Church Year. It is not able to say the Creed without mental reservation. Yet it claims to be spiritual, beyond others; and studiously affects an exclusive right to the title Evangelical!

Nevin followed up his criticism with several essays that blamed the Puritans for losing sight of the sacraments and the corporate character of Christianity. This led him to study the Eucharistic theology of Europe’s Reformed and Presbyterian churches. Eventually Nevin’s argument provoked a lengthy and learned dispute with Charles Hodge over the nature of the Lord’s Supper. The Mercersburg theologian looked to Calvin for support in affirming the real presence of Christ (spiritually) in the Lord’s Supper, but Hodge tended in the direction of Huldrych Zwingli’s understanding of the sacrament as a memorial of Christ’s death.

Enter Schaff

Nevin soon received help from Swiss German historian Philip Schaff, who arrived in the United States in 1844. Schaff’s strengths as a church historian were particularly useful for trying to overcome what the Mercersburg theologians regarded as a false understanding of the Reformation.

Instead of arguing that Protestantism stands for the triumph of reason over superstition or freedom of conscience over church tyranny, Schaff (and Nevin to a lesser degree) stressed the continuity between medieval and early modern European Christianity.

This also had the advantage of supporting several of Nevin’s other contentions: that Puritanism was responsible for American Protestantism’s rejection of liturgical forms and sacramental life, and that anti-Catholicism in the United States, which was increasing in the 1840s, relied on a misunderstanding of the Reformation.

Most influentially the Mercersburg Theology was guided by an understanding of the Incarnation that linked the doctrine of Christ to ecclesiology and sacramental theology. Nevin and Schaff thought that a proper appreciation for Christ’s significance would lead to a recognition of the church as Christ’s body and the sacraments as embodiments of his ongoing salvation of his people—and, perhaps, to abandoning techniques such as the anxious bench. This was the German Reformed equivalent of the High Church movement that blossomed within the Church of England at roughly the same time (see “Taking the long view,” p. 15).

Nevin and Schaff had almost a decade of fruitful collaboration before their labors ran aground. Nevin so emphasized an incarnational understanding of the church as Christ’s body that around 1852 he considered becoming Roman Catholic. At roughly the same time, Schaff left Mercersburg to join the faculty at Union Seminary in New York City.

Meanwhile their efforts to put Mercersburg’s teaching into the German Reformed Church’s liturgy launched an almost two-decades-long controversy. It pitted those who wanted a worship service compatible with American revivalist sensibilities against others who sought to retrieve historic forms of Christian worship that used traditional written prayers and encouraged frequent Eucharist.

Nevin continued to serve the denomination and was a part of the committee on liturgical revision.He kept a low profile otherwise. He continued to teach at the seminary, which relocated to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and at Franklin and Marshall College, a school of the German Reformed Church in Lancaster. Schaff in contrast became Presbyterian and established himself as the leading church historian in the United States through multivolume textbooks, anthologies, and encyclopedias.

One anthology, The Creeds of Christendom (1876), introduced many classic confessions of faith to a nineteenth-century audience. In addition to Schaff’s path-breaking scholarly activity (he founded the American Society of Church History, still going strong), he also became a leader in Protestant ecumenism in both the United States and Europe.

Even so Mercersburg’s movement remained largely an isolated phenomenon that depended on a small ethnic denomination’s networks for distribution. In the end its most substantial contribution may be the liturgy that the German Reformed Church adopted in 1887 (a compromise that allowed for freedom while also including samples of older forms), as well as its provoking a body of theological reflection in the United States that drew upon German theological and philosophical developments.

At the same time, the writings of Nevin (and to a lesser extent Schaff) have periodically inspired American Protestants— Reformed and otherwise—who are frustrated by the individualistic, parachurch-driven, and experiential qualities of “born-again” evangelical Protestantism to look for alternatives.

Although the answers that Mercersburg supplied have many quirks and shortcomings, Nevin’s and Schaff’s recognition of the differences between modern evangelicalism and the Reformation has often prompted their students to reflect on the character of Protestantism at its origins and its rejection of Roman Catholicism.

Especially for those Protestants who look to the confessions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as a substantial and yet succinct summary of orthodox teaching, who underscore the importance of ordination and church oversight, and who engage in sober and reverent worship, Mercersburg has often been a fruitful path for exploring tensions between evangelical and confessional Protestantism. CH

By D. G. Hart

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #129 in 2019]

D. G. Hart is distinguished associate professor of history at Hillsdale College in Hillsdale, Michigan. He is the author or editor of over 15 books including Calvinism: A History and John Williamson Nevin: High-Church CalvinistNext articles

From Manhattan to the monastery

Kathleen Norris thought she would make her name as a poet. Instead her greatest legacy came from her spiritual memoirs.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait“We’re not done with virtue yet”

Many different approaches to recover from modern amnesia

Jennifer A. BoardmanRenewals and revivals

Recent organizations that have attempted to be forces of renewal and Christian unity while maintaining a commitment to historic orthodoxy.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitA church of the ages?

We asked some pastors and professors to reflect on what it means to recover from modern amnesia and how the ancient and medieval faith can inform the church of the future

Jason Byassee, Chris Armstrong, and Greg PetersSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate