From Manhattan to the monastery

IN 1974 emerging poet Kathleen Norris (b. 1947) embarked on a journey that surprised even herself. The cosmopolitan 27-year-old—born in Washington, DC, raised in Hawaii, and educated in Vermont—gave up working for the Academy of American Poets and moved from Manhattan to Lemmon, South Dakota, with her new husband, David Dwyer, also a poet. Her maternal grandparents had passed away, and someone needed to tend their home. The move set in motion Norris’s transformation into a beloved spiritual writer as she discovered the riches of Christian tradition.

The couple’s Manhattan friends thought the two of them had lost their minds when they moved to a town of 1,600 people. They anticipated staying only a few years while her mother (still in Hawaii) decided what to do with the house. Instead they stayed a few decades.

Dwyer struggled with severe clinical depression that made him suicidal and once led him to disappear for days. (The policeman who found him told Norris, “Ma’am, your husband was so depressed, I never saw a man so depressed as that.”) Though raised and confirmed in the United Church of Christ, Norris had no real commitment to it; interacting with her fundamentalist paternal grandmother had distanced her from the church. But as she tried to cope with Dwyer’s illness, she began to grow closer to the small country Presbyterian church where her maternal grandparents had been active.

Eventually she was asked to fill in as a preacher by someone who told her, “You’re a writer, you can preach.” She also began visiting a local Benedictine monastery:

There I was in western South Dakota, and there was this monastery 90 miles away that was offering some talks and lectures and music concerts and things like that, and out there those are hard to come by. . . . I stumbled into Morning Prayer. . . . I didn’t even know what the monks were reciting. But they were reciting the psalms.

The experience of hearing these ancient texts as living prayer was transforming. In 1986 she became an oblate of that monastery.

Norris started to write short essays relating Christian faith to everyday life, eventually collected in Dakota: A Spiritual Geography (1993). The original printing called for only 2,500 copies, but to everyone’s surprise the book became a New York Times bestseller. Norris once commented that her small church community cared little about her literary pursuits except for the time she told her pastor she had finally sold a poem to the New Yorker. He announced it as one of the “joys of the church” on Sunday morning.

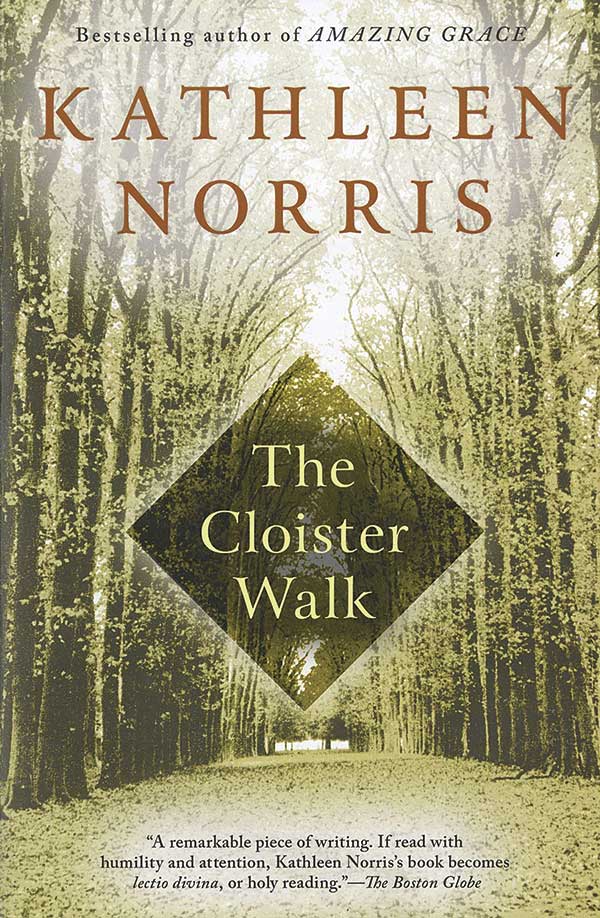

Norris’s follow-up memoir about life as an oblate, The Cloister Walk (1996), also unexpectedly topped best-seller lists. Norris, then in her fifties, suddenly found herself on book tours introducing the church’s traditions of prayer to thousands. Over the next decade, she would write a commentary on the Psalms, release Christian books for adults (and one for children) plus several books of religious poetry, and publish a memoir of her early life. Her writing helped explain the depth and relevance of Christianity to a generation of spiritual seekers.

Dwyer died in 2003 after a long illness, and the 71-year-old Norris now lives mostly in Hawaii, spending only the summers in Lemmon. She told an interviewer in 2015:

In a funny way, I have a monastic life there in Honolulu. I spend a lot of time alone in my apartment or walking. In a way, it’s a bit like my monastery. . . . I have a lot of solitude there, though I miss the silence of the Great Plains. But I think you can find your monastic cell, your commitment to prayer wherever you are.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #129 in 2019]

Next articles

“We’re not done with virtue yet”

Many different approaches to recover from modern amnesia

Jennifer A. BoardmanRenewals and revivals

Recent organizations that have attempted to be forces of renewal and Christian unity while maintaining a commitment to historic orthodoxy.

Jennifer Woodruff TaitA church of the ages?

We asked some pastors and professors to reflect on what it means to recover from modern amnesia and how the ancient and medieval faith can inform the church of the future

Jason Byassee, Chris Armstrong, and Greg PetersModern amnesia: Recommended resources

Recommendations on modern amnesia from CH editorial staff and this issue’s authors

the authors and editorsSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate