Our first woman reformer

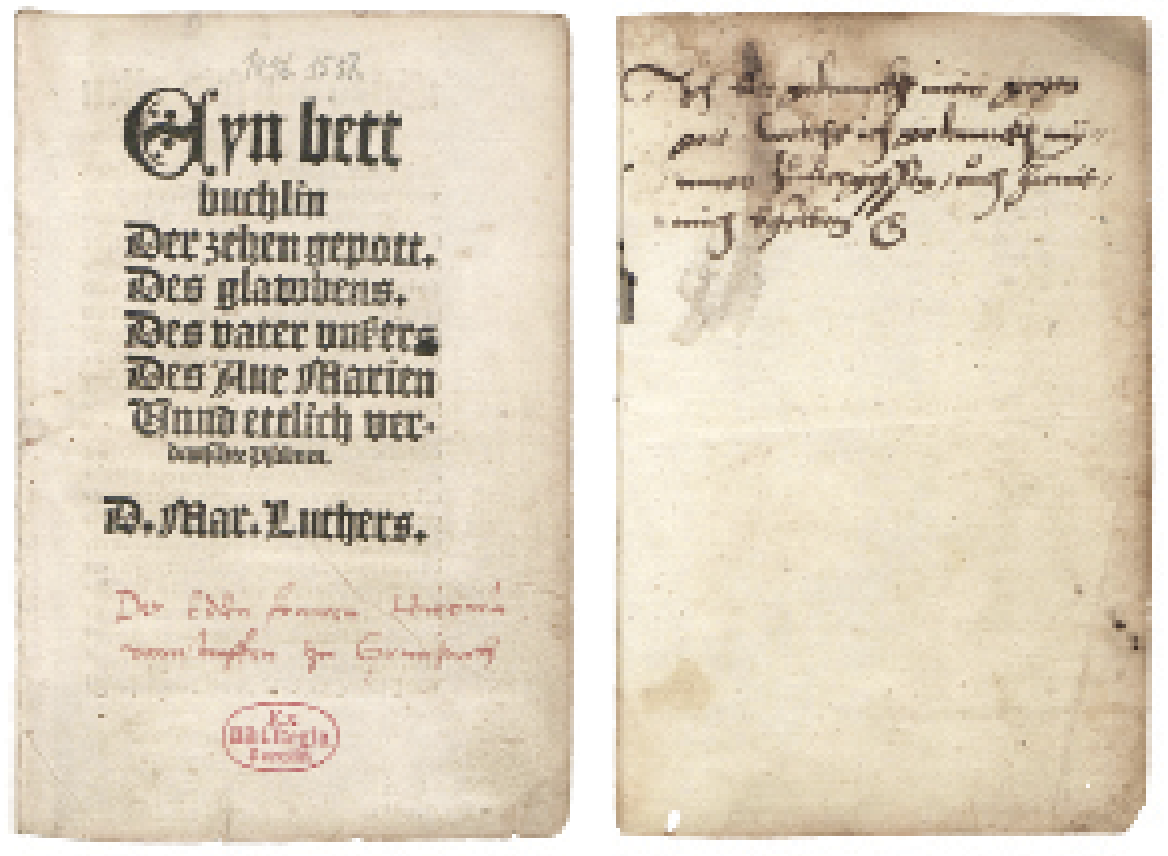

[Precious to Argula was Luther’s Little Book of Prayers (above), which Luther inscribed to her, and in which she wrote “Pray remember me to God, which I intend never to forget. I now commend myself to you.”]

DON"T LET THE UNUSUAL NAME TRIP YOU UP! Argula von Grumbach (1492–1554 or 1557) was a brave and extraordinary woman. Martin Luther (1483–1546) knew her well. We have a precious copy of his Little Book of Prayers with a dedication to her inscribed in his own hand: “To the noble woman Hargula von Stauff at Grumbach” (von Stauff was her maiden name).

Luther knew well what von Grumbach had suffered for the sake of the gospel: the abuse, the threats, the loss of status. This Bavarian noblewoman, with four little children dependent on her, had taken incredible risks. She had challenged the influential theologians of Ingolstadt University in Bavaria to a public debate with her in German about the legitimacy of their conduct in persecuting a young student.

Von Grumbach’s challenge was unheard of. Theologians didn’t lower themselves to debate with lay people, and still less with women, not to mention in German rather than Latin. They tried to ignore her, but friends had her letter to them published by the new medium of the time: the printing press. Publishers all over Germany and into Switzerland then raced to reprint it, no less than 15 times. It was a huge sensation: a mere woman challenging a university!

The woodcuts on the front covers portray von Grumbach, Bible in hand, alone, confronting an intimidated, bewildered group of scholars. The heavy tomes of their traditional theology and canon law lie discarded on the ground (see p. 21).

Pamphlets and poetry

What had led to von Grumbach’s letter? The Ingolstadt theologians had arrested and interrogated an 18-year-old student, Arsacius Seehofer (d. 1545), and threatened him with death if he would not renounce his evangelical views. Von Grumbach knew the young man and reacted with horror:

My heart and all my limbs tremble. Nowhere in the Bible do I find that Christ, or his apostles, or his prophets, put people in prison, burnt or murdered them. How in God’s name can you and your university expect to prevail, when you deploy such foolish violence against the word of God?

It was the autumn of 1523, in the exciting early years of the Reformation. Up to then lay people had possessed no right at all to debate theological matters. For one thing you had to be able to converse in Latin.

But in Zürich a public debate had just taken place in the spring of 1523 between defenders of the old church and the evangelical reformer Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531). It was conducted in German, and it had convinced the city fathers to promote the Reformation.

Von Grumbach avidly followed breaking news about the spread of reformist views. Probably this dramatic event in distant Zürich encouraged her to make her own protest—though she said that she did so in fear and trembling, certainly:

I suppressed my inclinations [to criticize Catholic preaching against Luther]; heavy of heart, I did nothing. Because Paul says in 1 Timothy 2: “The women should keep silence, and should not speak in church.” But now that I cannot see any man who is up to it, who is either willing or able to speak, I am constrained . . . .

She had found it impossible, following Matthew 10, to keep silent:

I find there is a text in Matthew 10 which runs: “Whoever confesses me before another I too will confess before my heavenly Father.” And Luke 9: “Whoever is ashamed of me and of my words, I too will be ashamed of when I come in my majesty,” etc. Words like these, coming from the very mouth of God, are always before my eyes. For they exclude neither woman nor man. And this is why I am compelled as a Christian to write to you.

Von Grumbach’s response held both substance and sensationalism. In words that ordinary people could understand, her pamphlet—which was soon followed by seven others from her pen—raised key issues about freedom of speech, the authority of Scripture, and the urgent need to reform

the church.

She pointed out that throughout Scripture and right down through the history of the church, the Holy Spirit had moved women like her to speak out, and she sensed that she stood in this prophetic tradition.

Knowing that clergy had dismissed women in the past as emotional beings too ill-equipped to tackle religious issues, von Grumbach rebutted this dismissal with 1 Corinthians: didn’t St. Paul say that every baptized member of the church is a temple of the Lord? She quoted the apostle in a poem she wrote the following year, responding to lewd and derisory attacks against her:

God’s spirit is within you, read,

Is woman shut out, there, indeed?

While you oppress God’s word,

Consign souls to the devil’s game

I cannot and I will not cease

To speak at home and on the street.

Luther's Bavarian champion

Von Grumbach was born in 1492—the year Columbus sailed—to the lively, educated, and chivalrous von Stauff family, with its seat in Ehrenfels Castle on the Laber River in Germany. Her first name recalls the noble Argeluse, a prominent character in the epic Parsifal about King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. When she was 10, her father gave her a beautiful Koberger edition of the Bible in German.

In adolescence the young Argula von Stauff moved from little Beratzhausen, near Regensburg, to Munich. The cultured Bavarian court—where Luther’s mentor, Johann von Staupitz (c. 1460–1524), was a much-admired preacher—became her university, so to speak. She learned to move comfortably among the great and the good—and the not so good.

When she married nobleman Friedrich von Grumbach in 1510, she set up homes in little Bavarian villages and market towns: Lenting, Dietfurt, Burggrumbach, and Zeilitzheim. There their children were born. Her time in small villages prepared von Grumbach for her later role in establishing Lutheranism in these rural areas.

Von Grumbach was not only an inspirational and controversial author but also a wife, mother, gifted correspondent, confidante of women, and mistress of her household’s day-to-day life. A creative tension existed between what we might call her “public” life and the local, personal networks she created, where she also exercised her influence.

Yet what undoubtedly most impressed von Grumbach’s contemporaries was her knowledge and apparently effortless mastery of Scripture. She knew great tracts of it by heart. Her pamphlets were a mosaic of biblical quotations, grouping together the prophets and Paul, the Psalms and the words of Jesus in a way that showed she had made the Bible her own.

Von Grumbach was no mere wielder of proof texts, however. Following the lead of Luther and Philip Melanchthon (1497–1560), she found a coherent, unitary message in the whole Bible:

Ah, but what a joy it is when the spirit of God teaches us and gives us understanding, flitting from one text to the next, so that I came to see the true genuine light shining out.

The gospel for her was light, illumination, and the liberating message of a gracious God.

Argula von Grumbach’s forthrightness, however, in publicly attacking the actions of the Ingolstadt theologians infuriated not only the latter, but every leading institution of her time: the university, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the Bavarian princes under whose rule she lived, and not least her own husband, “Fritz.” Critics pointed to his inability to “control his wife,” and Fritz lost his lucrative job in the service of the Bavarian dukes as punishment.

Pauper, pamphleteer, prophet?

Von Grumbach never received the public debate she asked for, but instead struggled with financial difficulties for the remainder of her life, pawning a precious necklace again and again to raise funds. We have wonderfully detailed lists of the provisions she ordered for her kitchen, often with apologies for the delay in paying for them.

Despite the chronic shortage of funds, von Grumbach took infinite pains with her children’s education, including that of her daughter, Apollonia. She carefully chose her children’s teachers—not only the very best available, but also pioneers of Lutheran education.

In her plans for the children, von Grumbach dreamed of preparing them for a different sort of church and society. Her vision was never restricted to the church in the narrow sense. Schools had to flourish too; the lifestyle of the nobility needed transformation; corruption and luxurious living should be banished from the land.

Even so von Grumbach was always up against it. Though her sons had huge respect for her, they could not shake off the influence of their peers, the male nobility—spendthrift, carousing, always quarreling and hunting.

Her eldest, Georg, wasted his opportunity to study in Wittenberg by becoming embroiled in debt. He was also badly wounded in a feud. Her second, impulsive son, Hans-Jörg, was killed in an unedifying local brawl. Young Apollonia died early, as did von Grumbach’s first husband.

Her second husband, Burian von Schlick, a Bohemian nobleman, ardently supported the Reformation but also died prematurely, imprisoned by his relatives over a family dispute. In a raw and violent society, tragedy upon tragedy befell von Grumbach. Near the end of her life, she herself was grossly mistreated, held captive, and forced to flee her family home in Bavaria.

It is all the more remarkable, then, that von Grumbach’s contribution to the Reformation is so memorable. Her rich correspondence complements the exceptional documentation of her life through the testimony of her eight pamphlets in their various editions. Providing a real treasure trove for readers today, her letters survived because authorities confiscated them as they gathered evidence for a legal challenge involving her son, Gottfried.

Much of von Grumbach’s correspondence relates to money matters, but other letters also survived, including a moving and sometimes hilarious back-and-forth with her children, communications from their teachers, and a raft of correspondence with more than a hundred other people, including diplomats, women friends, tradespeople, and even Jewish moneylenders with whom she was on good terms.

Von Grumbach’s contacts with reformers such as Melanchthon, Luther, and Andreas Osiander (1498–1552) in Nuremberg, and Urbanus Rhegius (1489–1541) in Augsburg signal her high standing. At crucial meetings of the Reichstag (parliament) in Nuremberg, and then at the famous Diet of Augsburg of 1530, she lobbied Protestant princes from the sidelines, urging them to stand firm by the faith. She also worked hard to heal the rift in the evangelical camp between the Wittenbergers (including Luther) and the South German and Swiss Protestants (including Zwingli) about the nature of the Lord’s Supper.

It has been estimated that some 30,000 copies of von Grumbach’s pamphlets circulated, and in a largely illiterate society, where they were read aloud, the actual audience would have been much higher. Her opponents described her in vile and odious terms (Jesuit Jacob Gretser, writing after her death, called her a “Lutheran Medea,” referencing a character from Greek mythology who had killed her brother and children). But for many contemporaries, she was a prophet before her time, and they compared her to Judith, Esther, and Susanna.

Von Grumbach’s reading of Scripture with a woman’s eye encouraged lay people in particular. Contemporaries hailed her courageous witness as almost unbelievable and as very rare for the female sex. Evangelical churches in little rural villages in Franconia, Germany, still trace their foundation back to her.

Living legacy

Awareness of von Grumbach’s contribution to the Reformation never totally died out. In the mid-sixteenth century, Ludwig Rabus reprinted her works, hailing her as one of God’s elect witnesses and martyrs. Encyclopedias in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries dubbed her a “Bavarian Deborah” with “spear and lance.”

In the nineteenth century, romantic biographies kept her memory alive—one by Eduard Engelhardt celebrates her “true manly strength,” as he puts it. Historical scholarship began at last to take von Grumbach seriously in the twentieth century; a critical edition of her writings has appeared in English and in German.

Schools are named after her and statues erected in the little villages where she lived (see p. 19). An Argula von Grumbach Society in Munich promotes her memory. In the last couple of years, an exhibition in Ingolstadt and a lively musical, of all things, in Münster have again brought her to public attention; the musical celebrates her as Argula von Grumbach: Mother Courage of the Reformation.

Today the cruel circumstances of von Grumbach’s life speak to our hearts while we are drawn to the prophetic character of her spirited writings and inspired by her exemplary courage. “I do not flinch,” as she said:

With Paul, 1 Corinthians 2, I say “I am not ashamed of the gospel which is the power of God to salvation to those who believe.”. . . What I have written to you is no woman’s chit-chat, but the word of God.

CH

By Peter Matheson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #131 in 2019]

Peter Matheson is an emeritus professor at Knox Theological College, Dunedin, New Zealand, the author of Argula von Grumbach: A Woman’s Voice in the Reformation and Argula von Grumbach: A Woman Before Her Time, and the editor of the scholarly edition of von Grumbach’s works. He is also the author of The Imaginative World of the Reformation and The Rhetoric of the Reformation and editor of Reformation Christianity and of the works of Thomas Müntzer, among many other books.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: Women of the Reformation

The Reformation through women's eyes

the editorsNot a soap opera

The women of the English Reformation were active participants in a theological drama

Calvin LaneShe would follow only Christ

From pamphlet writing to pastoral counsel, Katharina Schütz Zell fought for her right to speak

Elsie McKee“Christ is the master”: Margaret Blaurer

Blaurer was of use to the church as a single woman.

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate