Not a soap opera

[Queen Mary I of England]

PRESENTATIONS OF TUDOR ENGLAND, whether we find them in academic research or on cable TV, usually offer two overlapping storylines: on the one hand, we have the Reformation and, on the other, the dynastic soap opera that was the family of Henry VIII (1491–1547). Does that mean the Reformation in England was a sullied affair, one lacking theological substance? Was it simply the story of a lascivious king who wanted one divorce after another?

Even during the sixteenth century, some continental reformers suggested as much; Martin Luther, for example, had little respect for England’s bluff “King Hal.” Notwithstanding the critiques of Dr. Luther, many continental Protestant circles still believed God worked through anointed sovereigns—even in the messy bits of their lives.

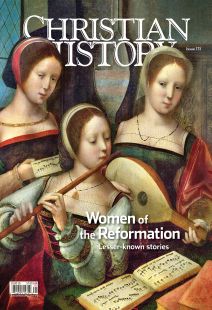

We shouldn’t forget that the “soap opera” aspects of the reform in England allowed women to play vital parts in a national drama. While women were certainly part of the story on the Continent (think of Argula von Grumbach, Katharina Schütz Zell, or Wibrandis Rosenblatt), the women in Henry VIII’s life—both his wives and his daughters—played enormously important roles in shaping Christian life, thought, and practice in early modern England. Not simply actors in a soap opera, these women and the parts they played left a strong legacy among English Christians.

The Spanish princess

The story we tell of the English Reformation often begins in the late 1520s with Henry’s desire to end—or more properly speaking, invalidate—his marriage to Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536). Catherine was the daughter of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castille, the “most Catholic monarchs” of Spain (titles granted to them by the pope in 1493). She had been previously married for one year to Henry’s older brother, Arthur, before his death in 1502. Henry argued that this marriage had been consummated, making Catherine Henry’s sister. The king used Leviticus 20:21 to argue that his marriage to Catherine was therefore incestuous and that God was punishing Henry by not granting him a male heir.

This claim was complicated by an earlier papal recognition that Catherine and Arthur had not consummated their marriage, and therefore, her marriage to Henry was emphatically not incestuous— and by Catherine being the aunt of the most powerful man in Europe, the devoutly Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

As the story unfolded, Henry moved to make himself supreme head of the church in England and therefore the arbiter of his own question in 1534. The seemingly earthy issues of sex and marriage had revealed a deeper question about authority. Catherine’s legacy rests in how she negotiated the challenge. She responded that she was loyal to the king and was his true wife while also remaining faithful to the “old religion.”

When it became clear that Henry’s move for supremacy would be packaged, to some extent, with the evangelicalism of continental Protestants, her witness mirrored the rhetorical strategy and self-fashioned identity of many “traditionalists” well into the latter half of the sixteenth century: a posture of fidelity to old ways, which included loyalty to both the old faith and the crown. In Catherine’s case her loyalty led to the annulment of her marriage and a short life in banishment—forbidden from seeing her daughter, Mary.

Such early “traditionalist” Catholics, like Catherine, shouted their loyalty both to the English crown and to their Catholic faith. Catherine’s “traditionalist” legacy continued for a generation or more. They were, sadly, trying to square a circle: loyalty to both king and pope. Others abandoned this seemingly insurmountable task.

A more aggressive form of Roman Catholicism emerged in England following the Council of Trent in the middle of the century, which included a religious stance quick to declare certain monarchs heretics and bastards. This different breed of English Catholics hid Jesuit missionaries and seminary priests trained overseas, and they later plotted against the crown. Nevertheless Catherine’s rather tragic witness—a heartfelt and seemingly sincere attitude toward both the church and her husband—set a powerful example for many conscience-stricken men and women in England and highlighted how Henry’s reformation began as a question of authority.

Executed, died, annulled . . .

We might be tempted to write off Anne Boleyn (d. 1536), Henry’s second wife, as simply a home-wrecker (or in the words of those loyal to Catherine, a “goggle-eyed whore”). However she was also a more complicated figure, becoming an active part of an evangelical network in England in the early 1530s.

Evangelicals like star preacher Hugh Latimer (c. 1487–1555) and new archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556) influenced her family and subsequently Boleyn herself. With definite connections to both Lutheran and Reformed Protestants on the Continent, their push for new understandings of Scripture in the Christian life no doubt affected Boleyn’s approach to turning the heart of the king.

For example, when the monasteries were dissolved, she ordered two of her chaplains to preach to the king about using the monasteries for evangelical purposes. Both Latimer and Simon Haynes preached that the abbeys ought to be converted into places for studying Scripture and relief of the poor, not simply liquidated for the royal coffers (which Henry ended up doing). After Boleyn overplayed her hand and failed to produce a male heir, Henry executed her in 1536.

The king eventually got his male offspring, Edward, by wife number three, Jane Seymour (c. 1508–1537). She, however, tragically died from childbirth. With an heir secured, the king’s priorities changed; his chief advisor Thomas Cromwell (c. 1485–1540) pushed for an alliance with the German Lutherans. Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves (1515–1557), the daughter of a Lutheran prince, in 1540 became the most curious of all his marital adventures.

Anne of Cleves’s father was a member of the Schmalkaldic League, a Lutheran defensive confederation, and the marriage was contracted without the two parties actually meeting. Henry had only been presented with a portrait of the young noblewoman by artist Hans Holbein, a painting he later declared to be misleading.

Once they did meet, Henry was not impressed and the marriage was never formally consummated. This botched marriage led to the execution of Thomas Cromwell—and it also helped to shape the ultimate direction of Protestantism in England. During the 1530s and 1540s, continental Protestants were still sorting themselves into two different and evolving confessional parties—the Lutherans centered in Wittenberg and northern Germany and the Reformed in the Rhine Valley of south Germany and Switzerland. Where English evangelicals would fit was not a forgone conclusion. The failure to join the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League via Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves only accelerated the movement Cranmer and others were making to align with the Reformed.

The Reformation as it proceeded after Henry’s death in 1547 under Henry’s son, the boy-king, Edward VI (1537–1553), and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer would situate the Church of England within an international communion of Reformed churches. There would be no close tie with the Lutherans. The story of Anne of Cleves became a critical part of that turn of events and, perhaps curiously, she outlived all of Henry’s wives—continuing to live in England, visiting court (where she had the title of “the King’s Beloved Sister”), never remarrying, and enjoying a pension well into the 1550s.

. . . Executed, survived

After Cranmer formally annulled the king’s marriage to Anne of Cleves, Henry swiftly reentered wedlock in July 1540 with wife number five, the vibrant 17-year-old Catherine Howard. The king was 49, and his marriage to the niece of the conservative Duke of Norfolk on the same day he had Cromwell beheaded signaled to evangelicals like Cranmer that they should proceed with caution. (In the early 1540s, Henry executed evangelicals and Catholics alike.) Famously unfaithful to her much older husband, the new queen’s affairs led her to the executioner only a year later.

It was pious wife number six, Catherine Parr, who would leave the greatest mark on Henry’s younger children, Edward and Elizabeth. Catherine was part of a Christian humanist network, and she regularly urged Henry to continue the church’s reformation—so much so that she came close to being arrested on heresy charges herself.

Catherine Parr’s greatest contribution to the story, though, was in supplying evangelical tutors for the heir and for the Lady Elizabeth. Under such influence Edward wrote to Cranmer at the age of seven, encouraging the archbishop’s promotion of the Word of God. The stories of Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr were critical in orienting the players who would be so influential in the next decade.

Battle of the heirs

One of the great ironies of Western history is that Henry, who was so concerned with leaving a male heir, left behind two daughters who made an even greater impact on English politics, culture, and religion than did their little brother. Edward VI was the first of Henry’s children to rule, but he did not do so for long; he became king at age 9 and tragically died at 16 (many suspect tuberculosis) in 1553. His desire that his Protestant cousin Lady Jane Grey should succeed him was thwarted, and Grey enjoyed only a nine-day reign before being convicted of high treason and executed a few months later.

As a result the daughter of Henry and Catherine of Aragon, Mary (1516–1558), succeeded to the throne; she and Elizabeth had been restored to the legitimate line of succession in 1543, though briefly disinherited again by Edward’s will. A devout Catholic like her mother, Mary ordered the Latin Mass celebrated for the soul of her dead Protestant brother.

It was, in fact, her commitment to the faith of Rome that created the concept in England of Roman Catholicism. Back in the fifteenth century, the pope in Rome had been a peripheral figure among even the most devout English Catholics. Now loyalty to the pope was a rallying cry, and faithfulness to him became an identity marker. Thus the leader of English Roman Catholics, a cousin of Henry VIII who had fled to Italy, came home to Mary to be her archbishop of Canterbury: Reginald Pole (1500–1558).

Mary would also bring another of her cousins, King Philip of Spain (1527–1598), to England to be her husband. Spain already had the reputation of being a hotbed for the Catholic Reformation and anti-Protestantism. This marriage solidified Catholicism in the Protestant English imagination as dangerously foreign.

But Mary knew that reconciliation with Rome would take more than a return of old Latin prayers and staunchly Catholic monarchs. For instance the question of the monasteries lingered; after the ejection of the monks, they had been sold to the nouveau riche as manor houses (note this well, fans of Downton Abbey). This obstacle was navigated with care in the 1550s, and the disaffected abbeys remained in lay hands.

Nevertheless Mary and Pole worked in earnest to resurrect the Mass across England, reestablish monastic communities where possible, and inspire loyalty to Rome via preaching. This campaign also featured the burning of key Protestants, including the imprisoned Thomas Cranmer.

In jail Cranmer had signed multiple recantations of his evangelical faith, and, according to the logic of inquisition, he should have been spared the stake. After all the triumph of inquisition is recantation: a heretic who repents. Burning was a last resort for purging the community.

Cranmer, however, was burned anyway—and thus made his famous recantation of his recantation, reversing his abdication of Protestantism at the last moment with high drama—because of a personal grudge held by Queen Mary. She wanted her pound of flesh from the heretic who, she believed, lured her father to divorce her mother. That does not mitigate the sincerity of her Catholicism any more than Anne Boleyn’s evangelicalism reprieves her from being the “other woman” in the breakdown of Henry’s first marriage. These women were just as complicated as the male players in the story.

Good Queen Bess or Nicodemite

Just like her little brother, Mary reigned for only a short time. What she hoped was a child in her womb turned out to be a tumor, and she died in 1558. This meant yet another of the women in Henry’s life would play a significant role in the religious history of England: Elizabeth, his daughter by Boleyn. Even as an infant, Elizabeth had played a symbolically Protestant part in the religious drama; the grumbling friars at her baptism grimly quipped that the water should have been boiling hot.

Though nurtured in her youth by stoutly evangelical chaplains and teachers, Elizabeth dutifully attended Mass during her older sister’s reign—a common practice for Protestants wishing to survive Catholic rule. While many fled for continental safe-havens like Frankfurt and Geneva, many other Protestants stayed and walked a dangerous high-wire—sometimes dissembling, sometimes compromising outwardly.

John Calvin in Geneva famously dubbed the French Huguenots who took this course “Nicodemites” and the name was also used for several leading English Protestants in the 1550s. The biblical reference is to Nicodemus who visited Jesus in John 3, but only under the cover of night.

Elizabeth’s personal high-wire act remained an undercurrent in her religious policies for the rest of the sixteenth century. From the start of her reign in late 1558, she advanced Protestant men who, like her, had stayed in England during Mary’s reign. Most notable among these were her lord chancellor, William Cecil (1520–1598), and her first archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker (1504–1575).

Elizabeth’s church was unmistakably Protestant and clearly part, once more, of an international communion of Reformed churches. She dismissed the torch-bearing monks at her coronation and only weeks after her accession, at Mass on Christmas Day, she demanded that the host (bread) not be elevated.

By the spring of 1559, the Book of Common Prayer, the Protestant form of worship developed during the reign of her little brother, Edward, was revived; in time the official Book of Homilies, a Protestant preaching aid, was expanded so that evangelical preaching could be heard across England.

It is often noted that Elizabeth, to the distress of many of the Protestants who came home from continental exile, had a taste for ceremony—not exactly Catholic but perhaps hankering after Lutheran patterns that had been abandoned by Reformed Protestants. Not only did she insist on the surplice (a white gown) for her clergy, she also kept a silver cross in her chapel royal, certainly not a part of the material context of Reformed prayer book worship anywhere else in England.

While Elizabeth demanded outward conformity, she did not pry beyond that—she did not, as it was often said, wish to make windows into her subjects’ souls. One could get along simply by showing up at one’s parish church for prayer book services. That would be a hallmark of the Church of England well into the seventeenth century.

Critical actors

In the end the women surrounding Henry VIII were certainly more than pawns in a sordid soap opera. Most of them had agency and were critical actors in a national religious drama. They charted paths many others followed. This is true whether we are speaking of Catherine of Aragon and traditionalists, Anne Boleyn and the early evangelicals or Catherine Parr and the later ones, Anne of Cleves and England’s shift toward the Reformed, Mary and resurgent Roman Catholics, or the idiosyncratic Protestantism of Elizabeth. Each represented key features of the story of the Reformation in sixteenth-century England, and their influence has long outlived them to shape English Christianity today. CH

By Calvin Lane

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #131 in 2019]

Calvin Lane is affiliate professor of church history at Nashotah House Theological Seminary, adjunct professor of history at Wright State University, associate rector of St. George’s Episcopal Church in Dayton, Ohio, and the author of The Laudians and the Elizabethan Church and Spirituality and Reform.Next articles

She would follow only Christ

From pamphlet writing to pastoral counsel, Katharina Schütz Zell fought for her right to speak

Elsie McKee“Christ is the master”: Margaret Blaurer

Blaurer was of use to the church as a single woman.

Edwin Woodruff TaitDangerous pamphlets

Margarethe Prüss helped advance the radical Reformation through her publishing

Kirsi Stjerna“God my Lord is even stronger”

Exemplary women of the Reformation with confidence in their convictions

Rebecca GiselbrechtSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate