Jesus the healer

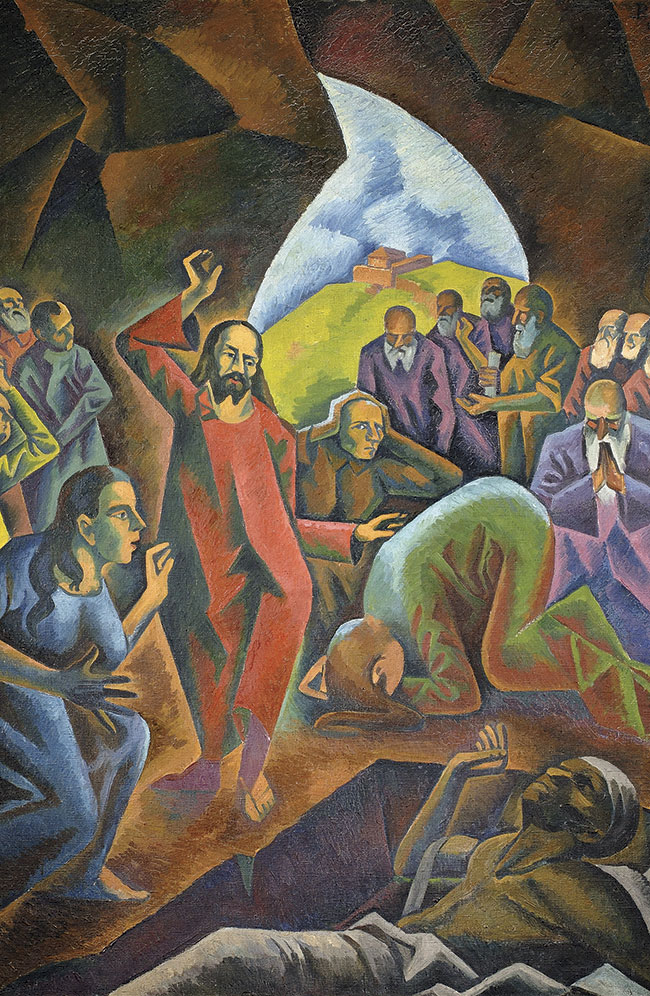

[Above: Bohumil Kubišta, The resurrection of Lazarus, 1911 to 1912. Oil on canvas—© The Gallery of West Bohemia in Pilsen]

In first-century Galilee, news spread quickly that Jesus healed sick people. The Jewish Scriptures had identified God as a healer (Ex 15:26) who had once restored a leper (2 Kings 5:1–15) and a dead child (1 Kings 17:17–24). The Gospels likewise brim with stories: a blind man runs straight to Jesus (Mark 10:46–52), a deaf-mute shouts praises (Mark 7:31–37), a paralyzed man walks home (Luke 5:17–26), lepers rejoin temple worship (Luke 5:12–16, 7:12–19), an epileptic boy is freed from a demon (Matt 17:14–18), a dead girl returns to her parents (Mark 5:21–24, 35–43), a chronically bleeding woman recovers instantly (Mark 5:25–34). Amazed and grateful, some left everything to follow Jesus; critics plotted to kill him. Moved by compassion Jesus even healed under circumstances (Mark 3:1–6) that fueled his enemies’ anger.

Power in prayer

Jesus taught his followers to share this priority, sending them out to preach the gospel and demonstrate that the kingdom of heaven had come near by healing the sick and casting out demons. The Greek word sozo—”save,” “heal,” or “deliver”—appears 110 times in the New Testament. After the Crucifixion Jesus’s followers kept healing people in his name. Peter caused a stir when a man lame for 40 years ran around the temple (Acts 3:1–11). When Paul healed a lame man, he could scarcely stop crowds from sacrificing to him as a god (Acts 14:8–18). Even Peter’s shadow (Acts 5:14–16) and Paul’s handkerchiefs (Acts 19:11–12) brought healing.

Not only apostles healed in Jesus’s name; Stephen and Philip waited tables, yet they too drove out evil spirits and healed the sick. The gifts of the Holy Spirit listed in 1 Corinthians 12 include healings, miracles, and discernment of spirits.

For three centuries the church added half a million new converts every generation. Most joined after witnessing a healing or an exorcism, a majority of healings taking place in private homes through the prayers of ordinary Christians. Converting to Christianity was risky, sometimes carrying a penalty of prison or execution. But people converted anyway, many convinced that Jesus is the most powerful healer.

In the fourth century, church growth accelerated, but healing drifted to the margins. After Constantine converted in 312 and the Edict of Milan (313) decreed toleration, Christianity transitioned from persecuted to state sponsored. Within a century, church members soared from five to thirty million. Many new converts were nominal Christians—attracted by gifts of money and food, or access to higher status jobs and marriages, but more likely to seek healing through familiar amulets and pagan spells than prayer in the name of Jesus.

Fleeing to the desert

Seeking to combat nominal Christianity, church leaders identified certain Christians as saints whose exceptional faith should inspire others and whose prayers were most likely to produce healing. By the fifth century, some of these serious Christians fled urban corruption. People in need of healing sought prayer from these “desert fathers.” The desert fathers often felt reluctant to pray for healing, lest it imply that they were so prideful as to think themselves saints. People were instead sent to shrines of martyrs to seek intercession from deceased saints.

Even church leaders began questioning the legitimacy of seeking healing. Committed Christians often sacrificed physical health by engaging in ascetic spiritual practices. Moreover, Christians were incorporating Neoplatonic notions of the body as a prison of the soul. When ascetic monk Jerome (c. 347–420) translated the Bible from Greek to Latin, he rendered sozo in James 5:15 as “save” (salvo) instead of “heal” (sano), the term that he used for a healing in Luke 8.

Few Christians had access to any other translation than Jerome’s until the Protestant Reformation. Even after the Bible became available in vernacular languages, versions like the one authorized by King James (1611) still followed the Vulgate in shifting emphasis from physical to spiritual healing: “The prayer of faith shall save the sick.”

By the Middle Ages, many Christians in Western Europe expected healing to be rare. Church leaders placed restrictions on who could pray for the sick or exorcise demons. The primary purpose of healing shifted from compassion for the sick to proving the holiness of those praying. Anointing of the sick with oil—encouraged in James 5—became a sacrament, but now only priests could perform it. Sacraments, by definition, always work. Because not everyone anointed recovered physically, the primary purpose was deemed spiritual preparation for heaven. Anointing of the sick was renamed extreme unction around the twelfth century; also called last rites, it was limited to those in danger of death who had received the sacrament of confession. The harshness of penances assigned for sins discouraged many medieval Christians from going to confession before they were so close to death that the priest might excuse them.

During the Protestant Reformation, Roman Catholic authorities challenged Protestants to prove their novel doctrines with miraculous healings. The Reformers denied needing miraculous proofs because they were not preaching new doctrines but only the Bible. John Calvin (1509–1564) promoted the doctrine of “cessationism”—that Jesus ceased healing after the apostolic era, just as soon as the gospel could spread through the Word alone. Calvin (who often fell sick himself) dismissed Catholic healings as superstition or demonic deception, while teaching that God sends sickness to chastise sinners; rather than combat sickness as demonic, Christians should passively resign themselves to God’s will.

As the Age of Enlightenment swept across eighteenth-century Europe and North America, many Western Christians questioned the compatibility of miraculous healing—or anything attributed to the activity of spirits—with natural law. By the early twentieth century, a growing number of skeptical philosophers, scientists, and theologians had reinterpreted biblical stories of healing and exorcism.

Some raised questions about the historical reliability of miraculous biblical texts; others suggested naturalistic mechanisms for healing, such as the power of suggestion, or proposed reading miracles metaphorically. Conservatives reaffirmed literal interpretations but restricted healing to a past dispensation in which God interacted with humans by different rules than those governing the modern world.

Fourfold gospel

But healing never disappeared from church practice, and stories of divine healing can be found in every time and place where the gospel has been preached. Luminaries from Augustine (354–430) to Martin Luther (1483–1546) to John Wesley (1703–1791) told such stories. Catholics often undertook pilgrimages to healing shrines like the one established in Lourdes, France, in 1858.

In nineteenth-century Germany and Switzerland, reports of healings and exorcisms by Lutheran pastor Johann Christoph Blumhardt (1805–1880) and laywoman Dorothea Trudel (1813–1862) captured attention. People came from far away to see and seek healing for themselves. To accommodate visitors, “healing homes” provided retreats for the sick to study the Bible’s promises of healing and receive prayer.

The nineteenth century was an exciting time for many Protestants as revivals spread across Europe, North America, and Australia, and missionaries fanned out across every continent. Many reported not only a “new birth” experience of forgiveness from sin through faith in Jesus, but also a “second blessing” of sanctification or holiness—an infilling of the Holy Spirit bringing freedom from the pollution and power of sin. Some Christians reasoned that if sickness is a consequence of sin, it should be possible to experience freedom from sickness as well as from sin.

Leaders of an emerging, globally networked divine-healing movement spoke of a “fourfold” or “full” gospel: Christ as Savior, Sanctifier, Healer, and Soon Coming King. As prophesied in Isaiah 53:5, Jesus, through his death on the cross, had made a full atonement for both sin and sickness, as “with his stripes we are healed.” Christians appropriated these blessings with the “prayer of faith” urged by James 5. Nineteenth-century teachers on healing, such as Canadian A. B. Simpson (1843–1919), founder of the Christian and Missionary Alliance, discouraged praying for healing “if” it is God’s will; they argued that the Bible reveals God’s willingness to heal and that Christians should confess their sins, claim God’s promise of healing, and then act as if healed—ignoring any remaining symptoms and using Christ-given strength to live for God and testify to others.

This understanding suggested that reliance on medical treatment—which many patients disliked anyway because of costs, side effects, and failures—showed lack of faith in God. Although many people’s symptoms disappeared after acting in faith, those who remained ill were sometimes charged with lack of faith or holiness, or died from preventable diseases such as malaria.

During the twentieth century, three “waves of the Holy Spirit”—the Pentecostal revivals of the 1900s, the Charismatic renewal of the 1960s, and the Third Wave of the 1980s—encouraged prayer for healing and other gifts of the Holy Spirit. As a result of Vatican II, the Catholic Church reaffirmed the purpose of physical healing and restored extreme unction to its original name, anointing of the sick. It also validated lay practice of spiritual gifts.

The Charismatic renewal reconciled some Catholics and Protestants, brought healing into mainstream churches, and eased tensions between prayer and medicine. In speaking of “divine” healing, rather than “faith” healing, leaders shifted focus from human faith to God’s love and power, and shifted blame for failures from human shortcomings to a cosmic battle between God and Satan. Although nineteenth-century views persisted in the Word of Faith movement of the 1970s, most Charismatics and Third Wavers came to understand faith more flexibly, trusting God to heal through medicine or psychotherapy as well as prayer, all the while acknowledging symptoms and praying as often as needed.

Storefront healing

Prayer for healing also become more democratized. Evangelists continued to preach the gospel and pray for the sick in large-scale services. But ordinary Christians increasingly prayed for family, friends, and strangers in hospitals, bedrooms, and grocery stores. At storefront healing rooms (nonresidential successors to healing homes), no fees are collected; instead, two or three lay Christians—Protestants and Catholics side by side—volunteer to pray for one person at a time, afterward reminding them to return to their doctors and continue taking prescribed medications.

By the year 2000, more than half a billion Christians belonged to churches that took biblical healings as modern models. Although many Western missionaries were cessationists, Christians in the Global South typically came to faith through healing or deliverance—their own or a family member’s. While Westerners questioned the existence of spirits, much of the world asked which spirit is the most powerful. For people plagued by sickness, poverty, violence, and insecurity, a “gospel” that is truly good news not only provides assurance for the afterlife but also meets practical needs, including for health and financial provision.

Today, as in the past, divine healing practices are more widespread and diverse than is often recognized. Identifying healing with the most visible, memorable examples—wealthy televangelists promising prosperity, high-profile scandals, children dying after their parents refused to take them to the doctor—scarcely scratches the surface.

Medical doctors—73 percent of whom, according to one national US survey, affirm that God heals today—often encourage their patients to seek prayer; they study medically remarkable healings and offer to pray for patients. The stories in these pages offer a more nuanced picture of how the global church has grown as more and more people conclude that Jesus is the most powerful healer. CH

By Candy Gunther Brown

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Candy Gunther Brown is professor of religious studies at Indiana University, author of several books including The Healing Gods and Testing Prayer, and editor of Global Pentecostal and Charismatic Healing.Next articles

Astonishing deeds

Biblical and early church testimony present Jesus as a healer and miracle worker

Craig Keener and Médine Moussounga Keener“We have prayed three people on the brink of death back to life”

Healing in the Protestant Reformation

Ronald K. RittgersSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate