Miracles of power and grace

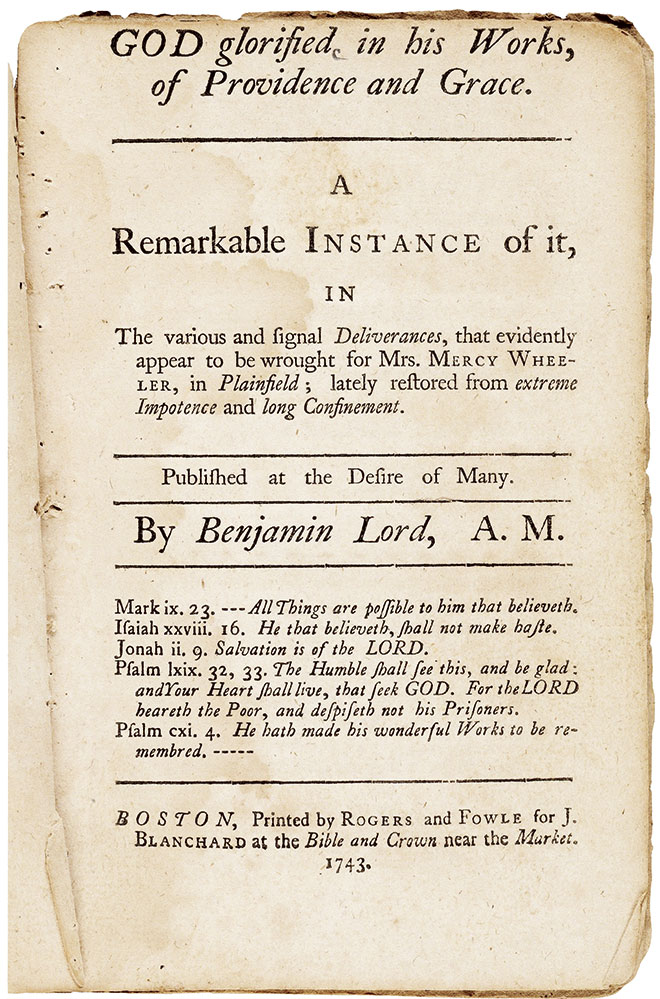

[Above: Benjamin Lord, God glorified in his works, of providence and grace, 1743—Yale Univeristy Library Collections]

Mercy Wheeler (1718–1819) was confined to her bed from the age of eight to twenty-five after a childhood malarial fever. Though her body wasted away and she lost her voice entirely, in brief moments of strength, she called on others—especially young people—to learn from her suffering. She proclaimed through her writing that though life is fragile and short, God is faithful even through illness. Her story caused quite a stir as leaders of the Great Awakening debated the Holy Spirit’s role in the church.

Something incredible

In early 1743, when Wheeler was 25, her condition slowly began to improve. She could sit up in bed and move a bit with crutches, but was still too weak to walk unassisted. In May of that year, she asked a local Congregationalist minister, Hezekiah Lord (1698–1761), to preach at her family’s house. Wheeler became confident God would do something incredible, repeating the words of John 11:40—“If thou wouldst believe, thou shouldst see the glory of God”—as she waited for Lord to arrive. When he came he preached on Isaiah 57:15—“to revive the spirit of the humble.”

As she listened Wheeler believed God meant these words especially for her. Affected by this conviction, she began to shake involuntarily. Attendees carried her back to her bed, convinced that she needed rest. After a brief moment of doubt, Wheeler became even more confident that God was healing her.

She stood up. Her disconnected tendons and atrophied muscles filled with new strength, and she walked around the room several times. As astonished witnesses watched, Wheeler yelled, “Bless the Lord Jesus, who has healed me!” (She lived to the age of 100.)

Wheeler’s dramatic healing occurred amid what historians call the Great Awakening, a series of religious revivals that began in the 1730s and continued throughout the century across North America, Britain, and continental Europe.

Ministers urged people to repent of their sins and devote their lives to righteous living and pious activities. Revivalists described this process as conversion, the “new birth” that Jesus proclaimed in John 3, and preaching this gospel became the basis for a transdenominational evangelical movement.

All evangelicals acknowledged the Holy Spirit’s role in conversion, but revivalists in North America disagreed about the extent of the Spirit’s work. Should they expect the dramatic miracles and spiritual signs that marked the apostolic era? Two clear camps formed, the moderates and the radical evangelicals.

Moderates emphasized the spiritual healing of conversion as the Holy Spirit’s chief work. God is sovereign and can bestow a “special providence” of physical healing whenever he wishes. But Christians ought not to expect instantaneous, miraculous healings.

Radicals, however, saw the revivals as a new kind of apostolic era. The Holy Spirit is instigating conversions, yes—but also dreams, visions, and powerful healings. The restoration of Wheeler (and others like her) brought the disagreements between moderates and radicals about the Holy Spirit’s work to the forefront.

Moderate evangelicals found it difficult to deny the connection they observed between spiritual renewal and physical health. In his congregation in Northampton, Massachusetts, Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) noted that during times of revival, “Satan . . . seemed unusually restrained.” Conversions appeared to improve mental and physical health within the community. As revival weakened, melancholy, depression, and sickness returned.

John Moorhead (1703–1773), a Scots-Irish Presbyterian minister in Boston, recorded several instances of individuals whose conversions led to dramatic physical recoveries. For Moorhead these healings validated the revival as a “legitimate work of God.”

In addition to restoration of health, revivals even in the moderate-led churches often saw people experiencing trances as well as bodily fits and convulsions. Moderates consciously chose not to use the word “miracle” to describe these manifestations of the Spirit. For many Protestants of the time, instant healings were a phenomenon characteristic of Roman Catholic superstition.

George Whitefield (1714–1770), the most celebrated evangelist of the period, spent his entire career denying this kind of “enthusiasm.” Though he believed that miracles and healings had confirmed the legitimacy of Christianity during the apostolic era, he thought such workings of the Spirit were unnecessary now. Spiritual health for eternity is most important, and the miracle of conversion is the chief work of the Holy Spirit.

God glorified in his works

Wheeler’s healing challenged the moderates’ hesitancy to affirm miracles. Moderate Congregationalist pastor Benjamin Lord (1694–1784, cousin to Hezekiah) wrote the most popular account of Wheeler’s healing from his firsthand perspective. In a sermon two weeks after the event, Lord refrained from calling the healing a miracle. In his published account of Wheeler’s healing, God Glorified in His Works (1743), Lord reminded his readers of Jesus’s healings, “when the Miracles of Power, in healing Men’s Bodies, were attended with those of Grace, in the healing of their Souls.”

Rather than celebrating Wheeler’s healing as a miracle, Lord understood it as an inspiration to the greater miracle: the conversion of unbelieving souls. Lord understood the mind of his eighteenth-century readers and their suspicion of miracle stories: a letter to the editor of the Boston Evening-Post soon cast doubt on the revivals and Wheeler’s healing: “However such Miracles may go down in Popish Countries, I trust they will be but little regarded in this Land of Light.”

A revival supporter responded by pointing out the many examples of healing in Protestant churches throughout the centuries. The Evening-Post writer replied again, clarifying that he did not doubt Wheeler’s healing. He only questioned whether it was accomplished by “miraculous Operation” rather than natural or providential means.

Eliphalet Adams (1677–1753), a friend of Benjamin Lord, wrote to him too, concerned about the effects of Wheeler’s experience. Adams believed that pastors should expect spiritual healing, but was worried about radical awakeners who would read Lord’s description of Wheeler and begin expecting similar physical signs and wonders in their churches.

Wheeler’s experience was unusual in the level of publicity it generated, but it was not unique. The New England Baptist minister Isaac Backus (1724–1806) wrote about another bedridden woman, Mary Read, who also was instantly healed. On July 24, 1769, Read heard a voice say three times, “Daughter be of good Cheer, thy sins are forgiven thee, arise and walk,” and she did just that.

Indeed, reports of miraculous healings were so prevalent in the Great Awakening that even relatively moderate revivalist John Wesley (1703–1791), leader of the English Methodist movement, wondered if apostolic-era miracles were returning to churches. His missionaries reported diseases and maladies healed instantly through prayer, and his own brother Charles (1707–1788) experienced deliverance from lung inflammation during a Methodist prayer meeting.

When healing backfired

Radical awakeners were more likely to embrace the possibility of miraculous healings in their ministries. Whereas moderates held to the traditional belief that God could use sickness to build godliness in suffering, radicals understood bodily weakness as demonic attacks or divine judgment. When James Davenport (1716–1757), the most notorious radical minister in New England, suffered from a leg infection in 1743, he blamed his poor health on Satan. Davenport concluded he had embraced a “false Spirit” and God was punishing him for it. After much prayer his leg was healed.

Radicals’ confidence in miraculous healing could backfire, however. In 1763 New England itinerant Charles-Jeffrey Smith (1740–1770) believed that the Lord would instantly heal his severely damaged eye. Devoting an entire day to prayer, he woke up the next morning still in pain. Though he still entertained the possibility of gradual healing, Smith never recovered and died by apparent suicide seven years later.

Moderate and radical evangelicals agreed that the Holy Spirit was working in their churches, but they disagreed about the expectation of dramatic healings. Moderates saw Wheeler’s healing as a confirmation of her spiritual vitality. Radicals heralded it as a sign that the apostolic-era miracles were returning.

Benjamin Lord represented the moderate position in his assessment of Wheeler almost a decade after the healing. He noted that, though healed, Wheeler’s body was still marked by a “weakly Constitution.” More significant to Lord was her “unshaken constancy in Religion.” In his opinion her physical health was unrelated to her spiritual well-being. Most remarkable about her was not that she was healed, but rather that God used her example to encourage faith in others.

Radical evangelicals tried, unsuccessfully, to lure Wheeler away from her Congregationalist church. Though they failed, Wheeler still served as an inspiration for radicals decades after her healing.

Arguing that the sign of miracles was returning, radical New England minister Jacob Johnson pointed his readers to Wheeler: “See an impotent, whose feet and ancle [sic] bones were all disjointed, restored, by no other means but faith and prayer.” Early evangelicals agreed about the Holy Spirit’s power to heal suffering souls, but could not agree on whether to expect the Spirit to heal suffering bodies. CH

By Thomas S. Kidd and Samuel L. Young

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Thomas S. Kidd is distinguished professor of history, James Vardaman Endowed Professor of History, associate director of the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University, and author of numerous books including Who Is an Evangelical? and American Colonial History. Samuel L. Young is a doctoral student at Baylor University.Next articles

Marching to Zion

Stories from a nineteenth-century transatlantic faith-healing movement

Joel CabritaChristian History Timeline: The gospel brings healing

Church history is brimming with stories of divine healing; here is a timeline of some featured in this issue

the editorsPower in the blood

Divine healing at the Azusa Street revival and in early Pentecostalism

Gastón EspinosaSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate