From turmoil to peace

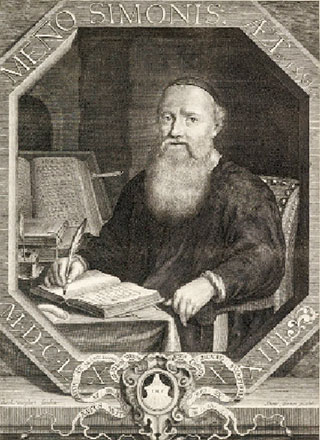

[Menno Simons]

IN 1536, when Menno Simons (c. 1496–1561) became an Anabaptist, he joined a movement in peril. Almost all of its initial leaders were dead, either by disease (Conrad Grebel) or execution (Felix Manz, Michael Sattler, Hans Hut, Hans Denck, Balthasar Hubmaier, Georg Blaurock, Jakob Hutter). Melchior Hoffman (1495–1533), the leader responsible for introducing Anabaptism to the Low Countries (modern Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg), was in prison, discredited for prophecies that had not come true.

No New Jerusalem for now

A 1534 coup in Münster had inspired some followers and established Anabaptist political and religious control, but it also terrified most observers, who now saw all Anabaptists as threats to law and order. Münster’s collapse in 1535 put the movement under further stress. Even groups who avoided all violence and political power were considered guilty by association. Persecution intensified everywhere.

In southern Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, places—like Strasbourg—that had provided some haven to religious dissenters now implemented harsher measures against Anabaptists. In addition Anabaptists were divided among themselves on theological and ecclesiastical issues. In the Low Countries, those who survived Münster suffered extreme disappointment; their promised New Jerusalem had come to naught. David Joris (1501–1556), a Dutch Anabaptist leader claiming to be a prophet and a third David, advised dissenters to stay under the radar with public conformity and compromise.

At this critical juncture, two reformers provided leadership: Menno in the Netherlands, and further south in Strasbourg and Augsburg, Pilgram Marpeck (c. 1495–1556). Both emphasized nonviolence, the role of community, and adherence to Scripture as guiding principles. Both were also passionately Christ-centered, but their different understandings of Christology led to two distinct visions for the church.

Menno was already 40 years old when he broke with the establishment and became an Anabaptist fugitive. But his convictions about true faith had been growing for years as a Catholic priest. By his own account, Menno was a mediocre priest. He was skeptical about transubstantiation, but chalked that up to his lackluster faith and did not concern himself with the religious reform sweeping through Europe. Rather, he wrote in a later memoir, he and clergy colleagues spent time “emptily in playing [cards] together, drinking and in diversions as, alas, is the fashion … of such useless people.”

Eventually Menno began to study the New Testament for the first time in his life, alongside the writings of Martin Luther, and he became convinced that transubstantiation is unscriptural. As he continued to learn directly from the Bible, Menno became an increasingly popular preacher.

Meanwhile in 1530 Melchior Hoffman had bap-tized 300 converts in Emden, and Anabaptism was spreading in the Low Countries. When in 1531 an Anabaptist tailor, Sicke Freerks, was beheaded in Leeuwarden, not far from Menno’s home in Witmarsum, Menno was intrigued: “It sounded very strange to me to hear of a second baptism. I examined the Scriptures diligently and pondered them earnestly, but could find no report of infant baptism.”

He searched the writings of the church fathers and contemporary reformers, becoming certain that infant baptism is contrary to the Word and intention of God. Nevertheless he failed to put his new conviction into practice: “Although I had now acquired considerable knowledge of the Scriptures, yet I wasted that knowledge through the lusts of my youth in an impure, sensual, unprofitable life and sought nothing but gain, ease, favor of men, splendor, name and fame. …”

“Blood on my heart”

A shocking event closer to home pushed him to act. In 1535 several hundred Anabaptists, led by an envoy from Münster, attacked and occupied a Cistercian monastery seven miles from Menno’s parish. The Frisian magistrate’s army defeated and killed most of them a week later. Guilt gripped Menno. Why had he been too cowardly to try to channel the zeal of these Christians toward peace before it was too late? He wrote,

After this had transpired, the blood of these people, although misled, fell so hot on my heart that I could not stand it, nor find rest in my soul. … These zealous children, although in error, willingly gave their lives and their estates for their doctrine and faith. … But I myself was continuing in my comfortable life and acknowledged abominations simply in order that I might enjoy physical comfort and escape the cross of Christ.

Silent no more, Menno began preaching what he truly believed; by 1536 he had left his parish and position, and soon underwent adult baptism and ordination as an Anabaptist elder. Bringing leadership to a fragmented, despised, and demoralized movement became his second calling, which he attacked more passionately than his first career. Though an outlaw Menno traveled widely in northern Europe—from Amsterdam to Cologne to Gdansk—preaching, baptizing, debating, and writing. One sixteenth-century martyrology describes him as one who “drew, turned, and won to God a great number of men, from dark and erring popery; yea, from the dumb idols, to the living God.”

This success put a substantial price on Menno’s head—100 guilders, to be exact: “Envious men thirsted with such exceeding tyranny and great bitterness for his blood and sought and persecuted him unto death, yet the Almighty God preserved him, and most miraculously protected him from the designs of all his enemies.” At Wüstenfeld in northern Germany, Menno finally found refuge in his old age and set up his own printing press on the estate of a sympathetic noble.

The death of the children of peace

Some of his associates were not as fortunate. One man suffered execution on the wheel in 1539 for sheltering Menno in his home. In 1546 authorities confiscated a house whose owner had secretly rented a room to Menno’s “poor sick wife [Gertrude] and her little ones.” And in 1549 Elisabeth Dirks, arrested on suspicion of being Menno’s wife (she wasn’t), endured imprisonment, inquisition, torture, and finally death. Menno felt these losses deeply: coupled with firm pacifist convictions, they led him to a passionate theology of suffering.

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Following Christ’s example, he wrote, believers must be prepared to suffer arrest, torture, and even death rather than use violence in self-defense. But that did not mean Christians had to seek martyrdom. Stories—unsubstantiated, but oft repeated—tell how Menno managed to stay alive by his wits.

A large part of Menno’s influence and legacy stems from his publications. His writings instructed and encouraged a church under persecution, while answering and challenging opponents. In 1544 Jan Claess’s head was cut off on Amsterdam’s Dam Square and stuck on a stake; his body was placed on a wheel to be eaten by animals and birds. His crimes included rebaptism by Menno and publication in Antwerp of about 600 copies of Menno’s books, destined for Holland and Friesland (now a Dutch province). Menno was planning to distribute some of these himself.

What did authorities fear inside the covers of these books? Menno described his followers as different from violent Münsterites: “The regenerated do not go to war, nor engage in strife. They are children of peace who have beaten their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning forks.”

He denounced forced community of goods, which had been practiced at Münster and seemed to threaten the social order, but he advocated responsibility and love in economic as well as spiritual matters. He sought religious authority in Scripture alone, emphasizing the teachings and example of Jesus and rejecting prophecies made by Münsterite leaders and by his rival David Joris, who claimed new insights and inspiration from the Holy Spirit.

A major theme of Menno’s writings is the new birth, or regeneration. To commit to Christ is to become a new person required to imitate Christ as much as humanly possible. He became famous among later Mennonites for a statement that reads in part, “True evangelical faith … cannot lie dormant. … It clothes the naked, it feeds the hungry, it comforts the sorrowful, it shelters the destitute, it serves those that harm it … it binds up that which is wounded … it has become all things to all people.”

In his later writings, Menno became increasingly concerned with a pure church “without spot and wrinkle” and insisted on strict discipline—banning wayward members from participation in the Lord’s Supper and even excommunicating and shunning them (avoiding all contact, including business, family, and marital relations; some Amish groups still practice this today). Controversy over shunning came to a head during Menno’s lifetime, and Dutch Anabaptists split into two factions, the first of many schisms to come.

Two visions of one church

Why such a harsh stance? Influenced like all Dutch Anabaptists by Melchior Hoffman, Menno embraced Hoffman’s view, rejected by most Christians today, that Mary contributed nothing to Christ’s humanity and acted only as a vessel for the pregnancy (based on an understanding of human reproduction derived from Aristotle in which the woman’s “seed” is completely passive). Menno wrote, “The entire Christ Jesus, both God and man, man and God, has his origin in heaven and not on earth.” This emphasizes the purity of believers, who are wed to Christ: the church as the Body of Christ participates in Christ’s divine perfection. There is no room for sinners.

In contrast stood Pilgram Marpeck, an Anabaptist leader who by profession was an engineer and civil servant in Strasbourg, Augsburg, and elsewhere—moving from place to place as necessitated by banishments or danger. He led Anabaptist groups wherever he was, participating in the conversation among Anabaptists and other reformers. Like Menno (and unlike most first-generation Anabaptists), he died a natural death.

Marpeck, like Menno, was a strong advocate for peace and rejected the spiritualism of contemporaries like Caspar Schwenckfeld (1489–1561), who minimized the need for external ordinances like baptism or the Lord’s Supper. Marpeck countered that believers need to be part of a community bound by love. The invisible and visible church are inseparably linked, just as are Christ’s two natures, divine and human. To be a true disciple of Christ requires a complete inner change, a fundamental conversion; it happens only through the grace of God, but the vehicles for grace are tangible practices like baptism and Communion.

But Marpeck had a deeper appreciation for human limitation than Menno. He walked a middle road between harsh legalism and an anything-goes spiritualism: the community of the faithful keeps one another accountable to standards of behavior and belief, but errs on the side of love. Rather than a church without spot and wrinkle, the church should be a place where committed Christians grow closer to God and more Christ-like in their practice of love.

Though Menno lends his name to mainstream North American Mennonites in the twenty-first century, their theology most closely resembles Marpeck’s. Yet his writings and leadership failed to leave a visible tradition. In fact his importance as a theologian and leader has only recently been brought out of obscurity. Menno became the namesake for many Anabaptists, who survived into the seventeenth century and beyond, yet his vision of a pure church is today practiced mostly by the Amish and other conservative groups. Nevertheless his message of peace and discipleship continues to speak across time and space. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Mary S. Sprunger

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Mary S. Sprunger is professor of history at Eastern Mennonite University, author of numerous articles on Mennonite history, and coauthor with Piet Visser of Menno Simons: Places, Portraits and Progeny.Next articles

Another accidental revolutionary

The rise of the Reformed tradition in France—and its most famous son

Jon BalserakCalvin, Councils, Confessions, Did you know?

Calvin the teacher, Menno the preacher, Elizabeth the queen, and those unpronounceable French Protestants

the editorsEditor's note: Calvin, councils, and confessions

Setting out to renew the church, the reformers divided and subdivided it

Jennifer Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate