Editor's note: Medieval lay mystics

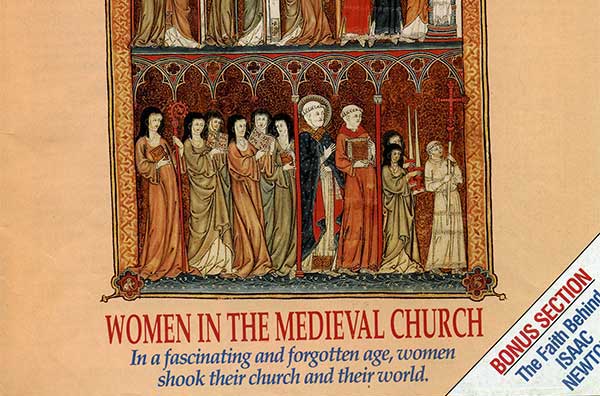

In the spring of 1991, I went to my college’s wall of mailboxes, twisted the little knob on the combination lock, and pulled out my first-ever issue of Christian History. I marveled at the beautiful cover of #30, Women in the Medieval Church. Little did I know that 27 years later, I would be writing to you as the magazine’s editor about an issue with a very similar theme.

That issue, along with issue #49, Everyday Faith in the Middle Ages, attempted to answer the question: what did it look like to be a medieval Christian? Kevin Miller’s words from issue #30’s editorial still ring true:

People danced around the Maypole, and built soaring cathedrals. They walked thousands of miles to view holy relics, and lit bonfires to ward off dragons. They illuminated some of the most beautiful books ever made, and fought plagues by carrying bouquets of flowers. They bathed in barrels, and saw visions of angels. And—impossible for us to understand—a massive Christendom ruled over all: kings and queens, abbots and abbesses, and countless peasant women and men.

Because the cultural differences are so great, it’s easy for us to question the faith of these believers. . . . We like things rational and orderly, so their emphasis on mystical visions perplexes us. We emphasize the individual, so their stress on communal life makes us blink. We live in an age of The Playboy Channel [we could now add the Internet], so their radical commitment to virginity strikes us as quaint.

New options for a new era

In this issue we’ve taken yet another path to understand these Christians, focusing on many of the most famous medieval mystics of the later Middle Ages, especially those who were not ordained. Scholars agree that around the twelfth century, a variety of forces led to a renewal of lay faith. Three centuries before the Reformation, the Bible began to be translated into vernacular languages (the everyday languages of a territory). Preaching in the vernacular became more common, and itinerant preachers traveled across Europe to reach new audiences with their sermons, calling people to a life of repentance.

Whereas many prior generations of serious seekers had joined religious orders to pursue a deeper spiritual life, now different movements sprang up giving laypeople new options.

Many people went on pilgrimages. Some women joined beguinages (see “A Spiritual Awakening for the Laity,” pp. 6–12). Some men became Franciscans or Dominicans, new kinds of religious orders that traveled around helping the poor and preaching rather than remaining behind monastery walls. Men and women alike became members of “third orders,” groups following part of the rule of a religious order while still living in the world.

And people from all these groups penned timeless devotional classics, many still popular, writing of their desire to reach a mystical oneness with the Christ they loved so much.

Here, I think, is the point where we can connect their lives with ours. We don’t bathe in barrels, and most of us don’t see visions. But we want to learn how to be more devoted to Jesus. Whatever the faults and misunderstandings of these medieval mystics, they did too. I responded to their call to be sold out to Jesus when I read issue #30 all those years ago, and I hope they will have a similar impact on you. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff-Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #127 in 2018]

Managing editor of Christian HistoryNext articles

Mystic women’s voices in the Middle Ages

Women outnumbered men in medieval mysticism.

Elizabeth Alvilda PetroffLike and unlike God

Much medieval mysticism had an unlikely source: the writings of an anonymous monk.

Edwin Woodruff TaitSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate