United with Christ in eternity and at the table

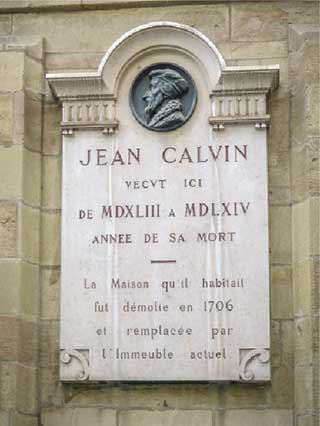

[Calvin memorial]

IF I SAY LUTHER, you say “95 Theses.” If I say Zwingli, you say “sausage in Lent.” And if I say Calvin, you say “predestination!” Predestination is a biblical theme and a perennial topic of Christian theology: how God’s sovereignty interacts with our free will. It was not something Calvin invented. Why has his name become so closely tied to the doctrine?

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound. . .

Some theologians throughout church history, like Augustine, have considered salvation the work of God alone creating faith and spiritual rebirth in a person (scholars call this monergism). Others have contended that while God’s grace is available to all, it is up to the individual to make use of it by believing and living as a Christian (synergism). Some late medieval theologians, like Gabriel Biel (d. 1495), were synergists. In Biel’s view predestination is based on God’s foreknowledge of a person using God’s grace to the best of his or her ability. God elects (chooses for salvation) those whom he foresees will do their best.

Martin Luther saw this synergism as a form of the old heresy of Pelagius (c. 360–418). And Luther had other late medieval theologians on his side, as well as his Augustinian mentor, Johannes von Staupitz (1460–1524). They emphasized predestination as God’s determination to give people faith and salvation, based not on God’s foresight of one’s faith or merit, but grounded in God’s grace alone. Biel contended that people must make the most of what is in them; Luther countered that all that is in the sinful person is more sin.

Calvin falls squarely within the Augustinian camp. God’s unconditional election of people, not based on any foreseen faith or merit, means salvation is entirely gratuitous and faith a free gift of God. He makes the traditional Augustinian distinction between election (God choosing who will be saved) and reprobation (God rejecting sinners who will not be saved). But to preserve both the goodness and justice of God, as well as the reality of human responsibility and free choice, Calvin needed to either leave certain questions in the realm of mystery (Lutherans commonly did this), or provide distinctions and nuances.

Calvin chose the latter course, and this made him a frequent target of criticism—especially regarding his doctrine of reprobation. But he saw predestination as an eminently practical doctrine that must be taught and preached as being of utmost comfort to the believer. He wrote, “We shall never be clearly persuaded . . . that our salvation flows from the wellspring of God’s free mercy until we come to know his eternal election, which illumines God’s grace by this contrast: that he does not indiscriminately adopt all into the hope of salvation but gives to some what he denies to others.”

Order Christian History #120: Calvin, Councils, and Confessions in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Calvin did not deny that human beings make real choices. But he contended that the relatively free choices human beings make fall within the scope of God’s providence. Moreover, like Luther, he took seriously the bondage of the human will that results from sin. Human beings are not as free as they pridefully fancy themselves, because sin affects their desires and choices. If salvation depended on a person’s choice, none would be saved.

Yet Calvin also needed to make clear that God is not the author of sin. People sin freely and voluntarily subject themselves to a bondage from which they cannot escape.

The sin and the sinner

Calvin wanted to affirm two biblical givens: that if a sinner is saved, it is solely because of God’s gracious election, and if a sinner is not saved, the only person to blame is the sinner. Calvin distinguished between reprobation and condemnation. He taught that God chooses whom he will elect to salvation and those whom he will leave in their sin (called the “reprobate,” that is, the rejected); but God does not condemn people because they are reprobate, but because they are sinners. Failure to understand this important nuance led many of Calvin’s opponents to conclude that his God was an unjust tyrant.

Calvin also distinguished between God’s eternal decree (the decision to elect some and reject others) and the execution of that decree in real time. God works out his eternal decree in genuine, cause-and-effect events and choices of the created world. Human beings make real choices, though sin limits the freedom of those choices, and in the elect the transforming power of the Holy Spirit motivates those choices.

Calvin warned against inquisitive speculation about God’s decree. One should not ask: why does God elect some and reject others? Or: what if I am one of the reprobate? Rather, one must look to Christ and his promises, and trust in Christ—which is far more reliable than trusting in one’s own decisions and one’s own wavering faith and efforts.

Criticism of his views drew Calvin into numerous controversies. Eventually he turned defense of the doctrine over to his trusted associate and eventual successor in Geneva, Theodore Beza (1519–1605), a gifted humanist scholar and poet whose theological and linguistic skills at least equaled Calvin’s own.

Jesus is here, but how?

What may surprise modern believers is that, in his own day, Calvin was just as engaged in controversies over the Eucharist, a hotly debated topic before and during the Reformation, as he was over predestination.

The dominant view inherited from the late Middle Ages was transubstantiation, Thomas Aquinas’s theory that the elements of bread and wine are transformed in their substance into the body and blood of Christ, while still retaining the external properties (called accidents) of bread and wine, such as taste and appearance.

None of the Protestant reformers accepted this view, but their alternatives varied widely. Huldrych Zwingli saw the sacrament primarily as a mental exercise of memory, a badge of identity, and a moral imperative to live as a Christian. At the other extreme, Luther sought to preserve a form of the bodily presence of Christ in the Eucharist without resorting to transubstantiation.

Protestant unity was a major motivation for Calvin, and his position between these two camps shifted along with the prospects for unity. When he wanted to find common ground with the Lutherans, he emphasized the presence of Christ in the Supper as a means of grace. But when confessional divides between Lutherans and Reformed began to deepen, he turned toward Zurich.

Calvin and Zurich theologians led by Bullinger forged the Zurich Consensus in 1549, and for a while Calvin moved much closer to Zwinglian emphases. Yet, in his last years, he returned to his earlier perspective, coming closer to the Lutherans once again.

Calvin adopted Augustine’s interpretation of a sacrament as “a visible sign of a sacred thing, or a visible form of an invisible grace.” He denied that sacraments are effective automatically or by their own power. Sacraments, he agreed with Augustine, are “visible words,” and their power comes not from the elements, but from the Word of God (rather than the words of consecration in the Mass) and from the Holy Spirit who creates the faith that receives God’s Word and promises. The sacraments confirm and strengthen the preached Word and have no effect apart from that Word.

Influenced by Strasbourg theologian Martin Bucer, Calvin developed a perspective that affirmed the true presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper. Unlike Luther and the Roman Catholics, Calvin did not understand this presence as physical, but mediated through the Holy Spirit. But in contrast to Zwingli, it was not “spiritual” in a human-focused sense.

For Calvin Christ was personally and truly present in the Lord’s Supper—but not in a bodily way, for his body remains in heaven at the Father’s right hand. When not attempting to conciliate the Zurich reformers, Calvin emphasized the Supper as a means of grace, in which Christ is not only represented, but actually presented to believers. What one receives through the sacrament, from the Spirit, is Christ himself.

Crucial to Calvin’s understanding is the sursum corda (“Lift up your hearts/We lift them up to the Lord”), one of the most ancient pieces of Christian liturgy. For Calvin this implies that one should not seek Christ in the bread and wine; rather, the elements cause us to look to heaven, where the incarnate Christ is seated at the Father’s right hand. The sacrament is a “mystical blessing”: Christ is not dragged down to earth, but in a mysterious way, the Holy Spirit lifts believers up into heaven for Christ to feed their souls, just as bread and wine nourish their bodies.

First, study your catechism

Perhaps because Eucharistic controversies loomed so large in his day, Calvin interpreted Paul’s requirement that believers “discern the body” as having to do with Christ’s physical body or sacramental presence, rather than with discerning that the poor also belong to the body of Christ. Thus he rejected the early church practice of inviting baptized children to the Supper.

After centuries of the church neglecting to teach laypeople the Bible and sound doctrine, Calvin emphasized the importance of knowing what one is doing when one participates. To allow very young children to partake would be tantamount to feeding them poison, he asserted. Children, he argued, must learn the faith from a Reformed catechism and make a profession of faith around the age of 10.

Because he thought that participation in the Lord’s Supper serves to strengthen a person’s faith and to bring him or her toward union with Christ, Calvin urged frequent (at least weekly) celebration of the sacrament. He condemned the medieval Roman Catholic practice of requiring participation only once per year. Calvin could not convince the Genevan authorities, however, who stipulated only quarterly celebration. The Lord’s Supper was, though, integral to the practice of church discipline in Geneva; the elders of the church had the duty to bar seriously erring people from the Lord’s Supper—but they were to do this primarily for the purpose of restoring such people to fellowship.

In the end, for Calvin, the Lord’s Supper was God’s gracious accommodation to our creaturely limitations and physical senses—pointing beyond this world, to the ascended Christ, who is not absent, but present with us; for when we receive the Supper in faith, he said, “we are truly made partakers of the proper substance of the body and blood of Jesus Christ.” There, united with Christ by the Spirit, one could find comfort and rest in his promises. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Raymond A. Blacketer

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #120 in 2016]

Raymond A. (Randy) Blacketer is lead pastor of First Cutlerville Christian Reformed Church in Byron Center, Michigan, and the author of The School of God: Pedagogy and Rhetoric in Calvin’s Interpretation of Deuteronomy.Next articles

Words to ponder from Calvin’s Institutes

Man never attains to a true self-knowledge until he has contemplated the face of God

John CalvinA faith that could not be contained

How Reformed Christians spread across a continent

Jennifer Powell McNuttSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate