Mystery cycles and miracle plays

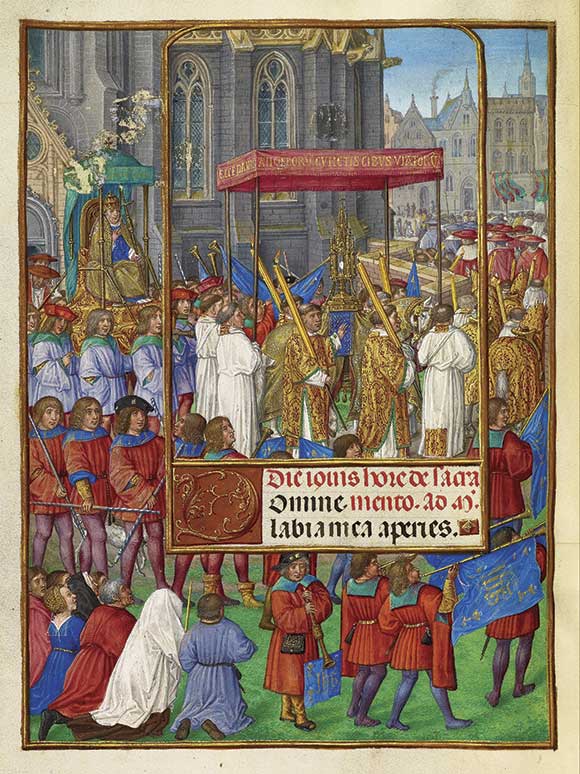

[Above: Master of James IV of Scotland, Procession for Corpus Christi, Tempera colors, gold, and ink on parchment, 1510 to 1520—Getty Center / Public domain, Wikimedia]

One need not search far or look hard for religious drama in the Middle Ages. There were Bible plays, saints’ plays, miracle plays, and so-called “morality” plays all over Catholic Europe. Of course, the Mass itself was a sort of production, with props, script, costumes, and ritual movements. Eventually, some dramatic elements, especially the Quem quaeritis? (Whom Do You Seek?) story of the women and the angels at the tomb, were included in the Easter services. We have definite evidence that in some religious houses, nuns (such as Hrotsvitha, see pp. 42–45) wrote and performed religious drama, usually about saints, sometimes based on pagan Roman plays. And a lively, improvisational, native dramatic tradition involving fantastic stories, stock comic figures (think Punch and Judy shows and characters costumed as hobby horses), and song and dance developed alongside and, in some cases, was absorbed into, the stories that mattered—primarily biblical stories and saints’ lives.

“Mystery cycles” (or Corpus Christi plays) and morality plays (or moral interludes) became very popular before the Reformation in England from the late fourteenth century until the middle of the sixteenth century. Many continued for a time afterward, usually with revisions that downplayed the roles of the Virgin Mary and the saints and, at least to some degree, fit better with new beliefs and practices. After the Reformation in England, representations of religious stories, characters, and themes were discouraged if not completely abolished (see pp. 17–20), though religion was not completely absent from the drama. Still, if a member of the court of King James (reigned 1603–1625) could have been transported to 1450, he would have seen biblical plays, saints’ plays, and other miracle plays regularly in local churchyards and town centers.

A DAY OF DRAMA

Specifically, if this same courtier had visited York on

June 4, the feast of Corpus Christi, he might have seen the entire spectacle of the biblical story, filtered through a mix of Roman Catholic doctrine, popular culture, and a strong dose of civic pride—all in one long day of performances, starting before sunrise at 4:30 a.m. with the arrival of the first pageant wagon.

The pageant wagon, an elaborate movable stage on wheels, would begin its trip from Pageant Green onto Mickelgate, stopping first at the gates of Holy Trinity Priory. There a civic official sat, checking the performance against the official script, or “register,” in this case of the first play of the day, “The Fall of Angels.” An actor performing the role of God (Deus in Latin), probably costumed in a golden mask, facial hair, and a wig and standing on some kind of upper level on the wagon stage, called the world and the Corpus Christi play into being:

Ego sum Alpha et O: vita, via, veritas, primus et novissimus.

I am gracious and great God without beginning.

I am maker unmade; all might is in me.

I am life and way, unto weal winning.

I am foremost and first; as I bid, shall it be.

Shortly, Deus created “nine orders of angels, full clear, / For love, in my worship, to sing,” along with the first “special effect” of the cycle, the sudden appearance of angels at different heights representing the different orders, in full angel gear. That gear included leather costumes coated with feathers. Immediately after their appearance, the angels broke into the Te Deum and a few minutes later sang the Sanctus.

Deus, too, sang praises, within the limits of Christian orthodoxy. He singled out one angel, costumed with something extravagant and gaudy:

Of these mights [powers] I have made, the most, next to me,

I make you, as master, to mirror my might;

I bid you obedient in bliss here to be.

I name you now “Lucifer, Bearer of Light.”

Of course, Lucifer’s special position as top angel and mirror of God wasn’t enough for him. Since “my power surpasses each peer,” he pridefully reasoned that “I shall be like the One who is highest on height.” But before you could say “special effect #2,” Lucifer and the rebellious angels fell to a lower level, where some kind of hellmouth, belching fire and smoke, received them. At the same time, the angel actors performed an amazing costume change into black masks and devil costumes:

Ah, ah! Help me! Helpless! So hot is it here!

This is a dungeon of dole in which I myself find!

What is my body, once comely and fair?

I am ugliest, loathsome, who once was sublime!

My brightness is black as a coal now;

My misery, endlessly kindling.

It makes me go growling and grinning!

Ah! Fury! I boil in woe now!

And that was just the first out of 48 plays!

PARADE OF PLAYS

Craft guilds sponsored each of the plays and their wagons, and many of them were amazingly appropriate. For example, the Shipwrights sponsored The Building of the Ark; the Fishers and Mariners, The Flood; the Vintners, The Marriage at Cana; the Bakers, The Last Supper; and the Pinners (pin makers), The Crucifixion. Each wagon was individually imagined and designed for its particular play, although there is good evidence that some of the action occurred on the street in front of the wagon as well. The wagons were hand drawn in and out of some 12 stations throughout the city, including the gate in front of York Minster and the final station, the Pavement (the commercial center of the city—site of markets, fairs, proclamations, and executions).

The final performance of the final play (The Last Judgment) would, almost certainly, have been after midnight. That would mean that, in years that the entire cycle was performed, 476 individual performances occurred in York on the feast of Corpus Christi. Before we ever again use “medieval” as an adjective meaning “primitive,” we should consider the commitment of the citizens of York (and other cities) in staging perhaps the most spectacular theatrical events in world history—Christian or otherwise—from the late fourteenth until the middle of the sixteenth century.

DRAMATIZING REDEMPTION’S STORY

Pageant content very much focused on biblical stories: the Creation, the Fall, the Incarnation, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, and the Last Judgment. As a specifically Christian version of biblical history, the pageants heavily emphasized the person and work of Jesus Christ. Old Testament characters and stories were included primarily if they were traditionally connected typologically with the New Testament, such as the stories of Noah, Abraham and Isaac, and Moses against Pharoah.

Eight plays roughly corresponded to the infancy and childhood of Christ—from the Annunciation to the Slaughter of the Innocents. Similarly, plays related to the Passion, Death, and Resurrection—from the Entry into Jerusalem to the Ascension—numbered 19. The cycle ended, as one might expect for late medieval popular religion, with four plays about the Virgin Mary, followed by the Last Judgment.

Much is made of the “incarnational” aspect of theater as an art form, but nowhere is this more evident than in the medieval biblical plays. Some might assume (and some might require) that “biblical plays” featured one-dimensional figures rather than “flesh-filled, blood-brimmed” humanity, as Gerard Manley Hopkins would later put it.

But the pageants gave us troubled Cain who resented his brother to the point of death; quarrelling spouses—Adam and Eve, and especially Noah and his wife, who yet saved the world of creatures; tormented Joseph, doubting yet loving his pregnant virgin wife; the anguished but resistant mothers of Bethlehem in the “Slaughter” play; wicked, ranting rulers like Herod, Pilate, and Pharoah; the rollicking but ultimately sentimental shepherds of the Townley Second Shepherds Play; the tender scene with Jesus and the woman caught in adultery, followed immediately in the same play by his encounter with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus; the disabled townspeople crying out to Jesus for help on his entry into Jerusalem at the York plays; and the sadistic soldiers, cracking jokes and mocking Jesus for over 250 lines as they nail him to the cross, only to find that they need some wedges because “the mortice-hole is over-wide; / that makes it wave instead of set.”

Among all this noise and tragicomedy, the figure of Christ, played over the day by 24 different actors, reigned from the cross. Here the Incarnation and the redemptive suffering of Christ spoke through the body of the mocked man on the cross in a powerful medieval popular lyric repurposed for the play, as one of many moments of direct address to the audience characteristic of medieval drama.

After the soldiers roughly swung the cross up into its position and their rude laughter died out, the play too settled into its groove. Likely some knelt, others wept, parents hushed their children, as they were drawn back into what all the noise and spectacle was about in the first place. Jesus, who had spoken only 10 of the 250 lines in the Crucifixion play heretofore, spoke from the cross:

All men that walk by path or street,

My sufferings take heed unto.

Behold my head, my hands, my feet,

And fully feel, before you go,

If any mourning may be fit,

Or torment, equal this unto.

My father that all pain may quit,

Forgive these men who these things do.

What they do, know they not.

Therefore, father, I crave

Their sins be punished naught.

But see their souls to save.

The audience wasn’t given much time to linger in this emotional identification with Jesus. The play and the soldiers, like life, must go on. They had people to execute, garments to gamble over, another performance a few hundred yards down the street.

1 SOLDIER: Well, hark! He chatters like a jay.

2 SOLDIER: I think he patters like a pie.

3 SOLDIER: Well, he’s been doing this all day,

Discussing mercy; who knows why?

We assume that many in the audience knew and felt why.

MORALITY PLAYS

When Western Christians think of allegory, they probably think first of John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). Of course, allegory had worked since long before Bunyan, and even long before Christianity, as a way of discussing or teaching philosophical, esoteric, or moral content. Prudentius (348–c. 413) in the late fourth century wrote Psychomachia, a highly influential poetic account of the battle for the soul of man in which seven sins (idolatry, lust, etc.) are opposed by seven virtues (faith, chastity, etc.).

Dante (c. 1265–1321) and many medieval Christians claimed that scriptural texts and even pagan texts could be read on four different levels, the literal and three different “allegorical” levels. Two of these we might classify as “religious” in that they dealt with salvation and questions of the afterlife (heaven, hell, purgatory). The other level is the moral level. The more or less allegorical plays from the medieval period typically dealt with that level and thus are called “morality plays.”

The major surviving English morality plays date from the late fourteenth to the early sixteenth century, and all deal with humanity and the struggle against sin in an allegorical manner. The five major ones are The Pride of Life, The Castle of Perseverance, Mankinde, Wisdom, and Everyman. The best-known of the morality plays, Everyman, is both a moral play and a salvation play. In it, the title character is summoned by death not just to die but to give an account or a “reckoning” of his life before facing the afterlife.

VICE AND VIRTUE

As such the play is very much about the virtues Everyman has neglected and the vices he has practiced. It is necessary for his salvation to rely upon his good deeds, but Good Deeds (the character) says something like “you should have thought of that earlier!” Just when it looks like it’s too late, Knowledge appears, who introduces Everyman to Confession, who gives him the whip of Penance, which he uses to scourge himself (as Good Deeds and Knowledge cheer him on). Scourged Everyman gets up with stripes on his back but a skip in his step, until Knowledge insists he wear the garment of Contrition for the rest of his life.

Although the play mentions incarnation and atonement, they seem tangential to the central action. This is an allegorical medieval play equally about morality and salvation, raising the significant medieval religious concern of how to die well.

Other morality plays are not nearly as clear cut as Everyman, the best example being Mankinde (c. 1470). Whereas Everyman is solemn to a fault, Mankinde, especially in its early critical history, was thought of as scandalous and profane to a most grievous fault. The lovable title character, a simple rural laborer carrying a spade, is taken under the guidance of Mercy, a clerical figure prone to long, boring Latinate moral sermons. Opposed to them both are a handful of lively “vice” characters (none of which clearly represents a traditional deadly sin): Mischief, New Gyse (New Fashion), Nought, Nowadays, and their pet devil, Titivillus, whom they bring in midplay, demanding that the audience pay for the thrill. Titivillus enters the stage with a blasphemous take on the entrance of Deus in the cycle plays: “Ego sum dominancium dominus [I am the Lord of Lords], and my name is Titivillus.”

Throughout the play the entertaining and sarcastic vices tempt Mankind, first to sin and finally to hang himself, since they have convinced him to despair. Finally, Mercy, who is neither entertaining nor lively, chases the comic vices from the stage, rescues Mankind, forgives him (again), and assures him that:

All the virtue in the world if we might comprehend

Your merits were not enough to buy the bliss above,

Not to the lest joy of heaven, of your proper effort to ascend.

With mercy you may [gain heaven]; I tell you no fable, Scripture doth prove.

The ending is characteristic of the strange mix of solemn and vulgar discourses in the play, both giving voice to the clerical speeches of “Mercy” and undercutting him. After he rescues Mankind by offering him God’s mercy, he then continues with 34 more lines of a tedious sermon on sin. He is interrupted, briefly, by Mankind’s simple, lovely exit lines:

Since I shall depart, bless me father, ere I go

God send us all plenty of his mercy.

Readers and audience members are not exactly sure where they stand in Mankinde’s uproarious and exhilarating dialogical imagination, and it continues to generate scholarly debate. But its quick switches between pompous sermons on sin and edgy vice characters reflect the uneasy but fascinating incarnational fusion of religious ideas and popular theatricality on display in much medieval religious drama, designed as much for the marketplace as for the church. CH

By Joe Ricke

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #152 in 2024]

Joe Ricke is a scholar, teacher, and writer with a lifelong emphasis on medieval and early modern drama.Next articles

Reforming drama

During religious change, English playwrights faced shifting attitudes about theater

Sarah R. A. WatersReading Christ between the lines

Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare wove Christian concepts into their works.

The editorsHeel kicking and holy jumping

Some early twentieth-century preachers enhanced their oratory with theatrical flair

Abram J. BookSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate