Sparks and trials

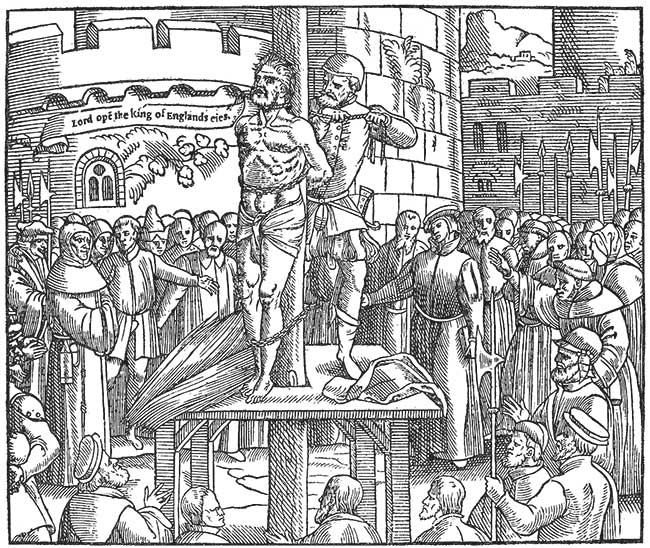

[John Foxe, Illustration of the Martyrdom of Tyndale in Book of Martyrs, 1563. Woodcut—Public domain, Wikimedia]

These reformers spoke and acted in the face of danger; two are well known, one had an unfamiliar story which inspired us and our readers alike.

Tyndale’s Betrayal and Death

By 1535 several Englishmen had hunted Europe for William Tyndale (1494–1536) under orders from English authorities. The one who actually succeeded in ferreting out the elusive Tyndale and bringing about his demise was a devious ne’er-do-well named Henry Phillips.

Phillips came from a wealthy English family. His father, Richard, had been a member of Parliament and high sheriff. In 1533 Phillips registered at Oxford for a civil law degree. Well-set to gain a good position, he ruined his prospects, however. Entrusted with a large sum of money by his father to pay to someone in London, he gambled it away.

After squandering his father’s money, Phillips felt afraid to return home. That is when he was hired to apprehend Tyndale. Someone supplied Phillips with a servant and a liberal amount of money. He made his way to Antwerp where he suspected Tyndale was living. He threw himself into the company of English merchants, and by his silver tongue and golden hand won the confidence of all except Thomas Poyntz (1480–1562), the man who gave Tyndale safe lodging.

Before long Tyndale found himself together with Phillips. Attracted by his easy manners and eloquent speech, Tyndale invited him to Poyntz’s home. Poyntz had misgivings about the stranger, but when Tyndale assured him of the man’s Lutheran sympathies, he suppressed his doubts. Within a few days, Phillips left. He had learned enough to know that it would be useless to work through the merchants or officers of Antwerp, who would almost certainly warn Tyndale.

So Phillips rode straight to Charles V’s court at Brussels, 24 miles away. He obtained the services of the emperor’s attorney and, with a few officers, headed back to Antwerp. Three or four days later, Poyntz left on business. Phillips struck without delay.

He arrived at the Poyntz home on May 21, 1535, and invited himself to lunch. He then returned to town, presumably to set officers in ambush. His scheme only required him to lure Tyndale into the trap. But Henry Phillips could not resist one more victory over his already-condemned prize. Almost as an afterthought, he asked Tyndale if he would lend him two pounds, on the pretext that he had, that very morning, lost his purse. Tyndale willingly loaned the money, and the two men left the house.

Outside Poyntz’s home they entered a narrow descent. Tyndale saw two figures ahead, sensed trouble, and moved back. Phillips stood over him, pointing down with his finger as a sign that this was the man; he then jostled Tyndale forward into the arms of officers, who bound him.

Tyndale was taken to the grim castle of Vilvoorde, six miles north of Brussels. Thrown into a foul, damp dungeon with squabbling moorhens outside and scurrying rats inside, he prepared for the end.

Poyntz was furious. This was an outrageous breach of the privileges of the English merchants. The merchants lodged a protest with the government of the Low Countries.

Complaints poured into the court at Brussels and into the court of King Henry VIII of England. Behind these protests was the never-tiring hand of Thomas Poyntz. But it was no use. Poyntz not only failed to free Tyndale, he was himself banished from the Low Countries, lost most of his business, was separated from his family for many years, and was left impoverished. He died in 1562. Henry Phillips gained nothing either. By 1542 he died as a prisoner himself—disowned by his family, by his country, and even by his collaborators.

Meanwhile in Vilvoorde Castle, Tyndale continued writing and translating. The winter was harsh, and he petitioned the prison governor for a few essentials to help him with his study and to warm his body. The letter, written in Latin, is the only letter in Tyndale’s own hand that

has survived.

After trial the reformer was condemned as a heretic and cast out of the church in August 1536. Doctors and dignitaries took seats on a high platform. Tyndale, wearing his priest’s robes, was made to kneel, and his hands were scraped as a symbol of having lost the benefits of the anointing oil with which he was consecrated to the priesthood. The bread and wine of the Mass were placed in his hands and at once withdrawn. This done, he was stripped of his priestly vestments, reclothed as a layman, and handed over to the state for punishment.

Two months later William Tyndale was brought out and urged to recant. Silence fell over the crowd as his lips moved in a final impassioned prayer: “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”—Brian H. Edwards, from CH #16

Legends About Luther

Martin Luther (1483–1546) became a legend in his own time. After the 95 Theses made him famous in 1517, stories and pictures painted him larger than life. One early woodcut portrays Luther as a young monk holding an open Bible, rays of light streaming from a halo surrounding his head.

Most misconceptions about Luther arose harmlessly and only gradually. Like all myths they contain a kernel of truth. Here are five often-told experiences from Luther’s life that need some clarification.

1. Thunderstorm “conversion”

After Luther finished his master of arts degree at the University of Erfurt, he embarked on the study of law until his return to Erfurt in 1505. Frightened by a thunderstorm near Stotternheim, he cried out: “Help me, St. Anna! I will become a monk.” This sudden decision made on the road in a flash of lightning reminded contemporaries of the conversion of St. Paul on the road to Damascus. But were the events actually alike? Not necessarily. Luther was certainly not converted in the sense that a formerly indifferent young man suddenly became serious about religion. Furthermore Luther ultimately regretted having made the vow.

2. Tower experience

Luther supposedly discovered the gospel all at once while reading Paul’s Epistle to the Romans in the tower of the Augustinian cloister. That notion was based on direct and indirect sources. A year before his death, Luther described how a new understanding of God’s righteousness finally came to him after he had meditated day and night on Romans 1:17–18. Table Talk, a compilation of notes by Luther’s students and associates, refers to his studies in the monastery tower and elsewhere.

It is most likely that the discovery came as the culmination of a long, painstaking attempt to understand Paul’s teaching on justification. As he diligently studied and lectured on the Bible in Wittenberg, Luther arrived at a new, positive understanding of righteousness as a gift of God received in faith.

3. Posting 95 Theses

Until recently the story of Luther nailing the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg was standard Luther lore. Nevertheless Luther himself never reported it. The tale stems from his colleague, Philipp Melanchthon (1497–1560), who was not in Wittenberg in 1517, and who did not record the incident until after Luther’s death. Catholic historian Erwin Iserloh pointed out in 1961 that the debate to which the theses were an invitation never took place in Wittenberg. Further, to provoke discussion of papal indulgences, Luther sent the theses to his superiors and to other scholars around Germany. According to Iserloh the theses were not nailed; they were mailed.

4. “Here I stand!”

In April 1521 Luther appeared before Emperor Charles V to defend his writings. At the end of his speech, the story goes, he spoke the famous words, “Here I stand; I can do no other. God help me.” The earliest printed version of Luther’s address gave these words, which were not recorded in the minutes. It’s possible they are genuine, but most scholars believe not. Luther’s speech was not a defiant, solitary protest, but a calm, reasoned account of why he had written the books piled on the table before him and why he could not recant their content.

5. Hurling an inkwell at the devil

Because Charles V declared Luther an outlaw, his prince, the Elector Frederick, had Luther kidnapped and hidden at the Wartburg Castle. Later stories of Luther’s 10-month stay at the Wartburg frequently told of his battle with the devil, who constantly disturbed his work—sometimes as a fly buzzing around his head. A famous story has Luther throw an inkwell at the devil. However, the first mention of the inkwell dates to the end of the sixteenth century and reverses the roles: the devil, dressed as a monk, threw an inkwell at the reformer.

This legend points to an important truth, though. Luther believed strongly in the existence of the devil with whom Christians are in constant battle. In his catechism Luther coached Christians to pray each day so that God would forgive their sins and strengthen their faith so they could survive this struggle.—Scott H. Hendrix, from CH #34

Our first woman reformer

Argula von Grumbach (1492–1554 or 1557) was a brave and extraordinary woman. Martin Luther knew her well: He dedicated a copy of his Little Book of Prayers to her in his own hand. This Bavarian noblewoman, with four little children dependent on her, took an incredible risk. In the autumn of 1523, she challenged the theologians of Ingolstadt University in Bavaria to a public debate with her in German about the legitimacy of their conduct. They had arrested an 18-year-old student, Arsacius Seehofer (d. 1545), and threatened him with death if he would not renounce his evangelical views. Von Grumbach knew the young man and reacted with horror.

Her challenge was unheard of. Theologians didn’t lower themselves to debate with laypeople, still less with women, much less in German rather than Latin. They tried to ignore her, but friends published her letter. Printers all over Germany and Switzerland raced to reprint it. It was a huge sensation: a mere woman challenging a university!

In words that ordinary people could understand, her pamphlet—followed by seven others from her pen—raised key issues about freedom of speech, the authority of Scripture, and the urgent need to reform the church. Von Grumbach pointed out that throughout Scripture and down through history, the Holy Spirit had moved women to speak out, and she sensed that she stood in this prophetic tradition.

Von Grumbach was not only an inspirational and controversial author but also a wife, mother, gifted correspondent, confidante of women, and mistress of a household. Yet what most impressed her contemporaries was her knowledge of Scripture. Her pamphlets quoted the prophets, Paul, the Psalms, and Jesus in a way that showed she had made the Bible her own.

Von Grumbach never received the public debate she asked for. However, she infuriated every leading institution of her time: the university, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the Bavarian princes under whose rule she lived, and her own husband, “Fritz.” Because he could not “control his wife,” Fritz lost his lucrative job in the service of the Bavarian dukes. Tragedies followed von Grumbach to the end of her life, when she was grossly mistreated, held captive, and forced to flee her family home in Bavaria.

Awareness of von Grumbach’s contribution to the Reformation never totally died out. In the mid-sixteenth century, Ludwig Rabus reprinted her works, hailing her as one of God’s elect witnesses. Historical scholarship began to take von Grumbach seriously in the twentieth century.

Her letters survived because authorities confiscated them as evidence for a legal challenge involving her son, Gottfried. They show she had contacts with many reformers. During crucial meetings she lobbied Protestant princes from the sidelines and worked hard to heal the rifts in the evangelical camp.

Today the cruel circumstances of von Grumbach’s life speak to our hearts while we are drawn to the prophetic character of her spirited writings and inspired by her exemplary courage.—Peter Matheson, from CH #131 CH

By Brian H. Edwards, Scott H. Hendrix, Peter Matheson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #150 in 2024]

Brian H. Edwards is a Christian minister, author, and editor; this article is adapted from his book God’s Outlaw. Scott H. Hendrix is emeritus professor of Reformation history at Princeton Seminary. Peter Matheson is emeritus professor at Knox Theological College, Dunedin, New Zealand.Next articles

A life of luxury meets the life of Christ

The lives of Christ and the saints filled Ignatius with a sense of “consolation.”

Katie M. BenjaminJohns worth knowing

A persecuted preacher, an innovative evangelist, and an "old African blasphemer"

E. Beatrice Batson, J. D. Walsh, Aubrynn WhittedThe golden age of hymns

Songs that spoke the language of Christian faith and aspiration

Vinita Hampton WrightFounding fathers

An innovative evangelist, a Christ-based preacher, and a pioneer missionary

James E. Johnson, Patricia Stallings Kruppa, Timothy GeorgeSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate