Johns worth knowing

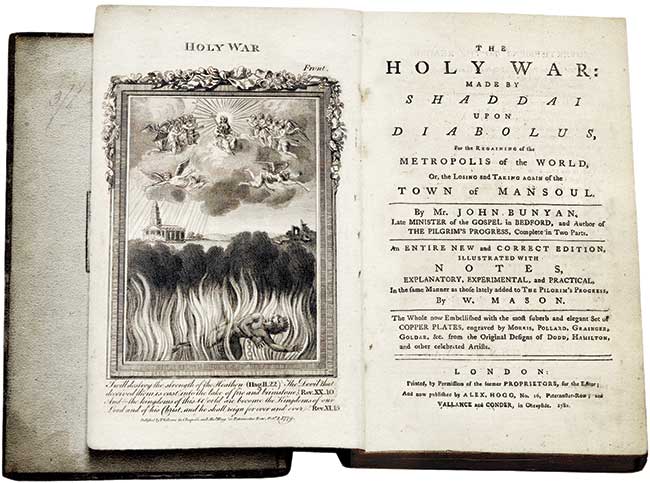

[John Bunyan, Frontisepice of The Holy War, 1792. Published by Alex Hogg, Vallance and Conder, London—Public domain, Duke University Libraries]

Here are our website’s most-searched men from the age of reason and revival.

Preacher, prisoner, pilgrim

John Bunyan (1628–1688) was born at Elstow, near Bedford, England, the oldest son of a tinker. When he was 16, the Parliamentary army summoned Bunyan in a county levy. What active service he knew is uncertain. After approximately three years, his company disbanded and he returned to Elstow and continued the family work. Bunyan loved music but had little money for instruments, so he made them out of his furniture.

He married twice. His first wife, as poor as he, brought him a simple dowry of two well-known Puritan works, Arthur Dent’s The Plain Man’s Pathway to Heaven and Lewis Bayly’s The Practice of Piety. They had four children, including a blind daughter, Mary, before she died. His second wife, Elizabeth, a brave woman, stood in the face of hostility, even when she feared John would be jailed for his preaching. They had two children.

Bunyan recorded his spiritual progress in a series of vignettes. He first discovered Christian fellowship by overhearing “three or four poor women sitting at a door in the room, and talking about the things of God.” Later he said: “They spoke as if joy did make them speak.” Bunyan found himself drawn into this same fellowship.

Prior to 1654 he met, and was counseled by, John Gifford, minister of the open communion Baptist Church at Bedford. He moved from Elstow to Bedford and began to preach near there. His ministry coincided with the Stuart Restoration of 1660, meaning that unauthorized preaching would be a punishable offense. Arrested in November 1660 for holding a conventicle (an illegal religious meeting), Bunyan was sentenced in January 1661, initially for three months, to imprisonment in Bedford jail. His continued refusal to assure authorities that he would stop preaching if released prolonged his imprisonment until at least 1672. Authorities granted him occasional time out of prison, and church records show that he attended meetings at the Bedford church. In prison he made shoelaces, preached to prisoners, and wrote various works.

Bunyan wrote much in prison, but his most memorable work was The Pilgrim’s Progress. Published in 1678, this book, next to the Bible, was for generations the most deeply cherished in devout English-speaking homes.

On January 21, 1672, the Bedford congregation called John Bunyan as its pastor. In March he was released from prison—even though he spent six additional months in prison in 1677—and on May 9, he was licensed to preach under Charles II’s Declaration of Indulgence. During the same year, the Bedford church became licensed as a Congregational meeting place. Bunyan’s dedication, diligence, and zeal as preacher, evangelist, and pastor earned him the nickname of “Bishop Bunyan.” Although he frequently preached in villages near Bedford, and at times in London churches, Bunyan remained a resident of Bedford.

Combined with preaching and pastoral responsibilities was a heavy writing schedule. He wrote more than 60 books, publishing the last in 1686. After riding on horseback in a heavy rain from Reading to London, Bunyan contracted a fever and died on August 31, 1688, at John Strudwick’s home in London. He is buried there in Bunhill Fields.—E. Beatrice Batson, from CH #11

Wesley Vs. Whitefield

John Wesley (1703–1791) and George Whitefield (1714–1770) had a complicated friendship. Whitefield came to Oxford University from the family inn and was working his way through college waiting on richer students. Still, Charles Wesley (1707–1788) asked him to join the “Holy Club,” drawing him into fellowship. Charles rather than John became Whitefield’s chief mentor. Whitefield spoke highly of both. He called John his “spiritual father in Christ,” addressing him as “Honoured sir” in letters.

In 1736 John Wesley entrusted the newly ordained Whitefield with oversight of the Oxford Methodists. Whitefield soon soared to national fame as “the boy preacher.” As Whitefield freely confessed, it went to his head. Though his evangelistic success far outstripped his former instructor’s, he showed Wesley deep respect. Still, as revival unfolded, young, exuberant Whitefield took the lead, dragging behind him the older, more cautious Wesley.

In spring 1739 Whitefield took preaching outdoors—first to the coal miners around Bristol and then to the street poor of London. Whitefield pushed the reluctant Wesleys to do the same. Now Whitefield and the Wesleys worked as equals. When Whitefield won converts, he relied on Wesley to help organize and instruct them.

A few months later, however, theological tensions came to a head. By 1740 two camps split the infant Methodist movement. The Wesleys, unshakable “Arminians,” denied predestination, yet the revival drew zealous recruits from the Puritan Calvinists. At first Whitefield was no predestinarian, but after sailing to America in 1739, contact with fervent Calvinists and reading Calvinist books changed his mind.

Even before Whitefield left, John had attacked the Calvinist theory of grace. In March he preached and published his passionate sermon, “Free Grace.” John feared that Calvinism propagated fatalism and discouraged growth in holiness. Charles feared that predestination represented a loving God as a God of hate. Whitefield, always more irenic than John, demurred before replying. Nonetheless, on Christmas Eve 1740, Whitefield wrote his riposte, defending the Calvinist doctrine of grace.

Wesley then provocatively published “Free Grace” in America. Whitefield, when invited to preach in Wesley’s headquarters at the London Foundery, scandalized the congregation by preaching election “in the most peremptory and offensive manner,” with Charles beside him, fuming. From then revival moved along parallel lines, and Whitefield’s growing “Calvinistic Methodist” societies rivaled Wesley’s “United Societies.”

Whitefield was a moderate Calvinist, and John Wesley allowed (for a time) that some souls might be elected to eternal life. When not overheated both men saw such issues as nonessentials. No merger of the two camps occurred, but there was at least reconciliation and an “agreement to differ” between the leaders. This friendship continued even though the old split remained. Ultimately what eased relations was Whitefield’s decision, in 1749, to abandon formal leadership of the Calvinistic Methodist societies. He thus posed no threat to Wesley as chief organizer of the revival.

Ultimately the two men complemented each other. Gifted Whitefield could scatter the seed of God’s Word across the world. Wesley, preeminently, could garner the grain and preserve it. On Whitefield’s death Charles penned a noble elegy. And at Whitefield’s request, his funeral sermon was preached by none other than his former opponent, John Wesley.—J. D. Walsh, from CH #38

An amazingly graced life

John Newton’s (1725–1807) mother had a strong Christian influence on him. She taught him Scripture, catechisms, and hymns. Tragically she died before he turned seven. At 11 he went to sea with his father, a merchant navy captain. John became a foul-mouthed and impetuous youth, shocking even the most hardened sailors.

Young Newton had no self-control. He briefly worked in a merchant’s office but lost the job due to “unsettled behavior and impatience of restraint.” Remembering his mother’s faith, he tried and failed repeatedly to turn his life around.

Pressed into the Royal Navy, he deserted to be with his future wife, Mary, whom he loved dearly. But he was caught, put in irons, and flogged. Allowed to leave the navy in 1745, he became involved in the slave trade, a business venture that quickly soured. A slave trader left him in West Africa, and the man’s African wife abused and enslaved Newton. In 1748 Newton was rescued and sailed home on the Greyhound.

The ship was caught in a severe storm. Newton prayed for God’s mercy. The storm calmed. By the time the Greyhound reached port, he was converted. However, he later admitted, “I cannot consider myself to have been a believer, in the full sense of the word.”

Newton married in 1750 and later adopted his two orphaned nieces. He returned to work as captain of a slave-trading vessel. Though Newton sympathized with the enslaved people he transported, he continued working in the trade. At times he fell into old temptations. It was four years before he left the active slave trade, but he continued to invest in the lucrative business.

Greatly influenced by George Whitefield and others, he pursued ministry. It took years for his ordination application to be accepted, but finally, in 1764, he was ordained in the Church of England. He served in Olney, where he would stay for 16 years. Newton started a weekly prayer service, which poet and lay minister William Cowper helped lead. The two wrote hymns to sing at prayer meetings, later published as the Olney Hymns (see p. 35).

Eventually Newton’s eyes were opened to the hideousness of the sin of slavery. In 1788 he published Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade. He repented for his active involvement in slavery and referred to himself as “the old African blasphemer” who had been saved by “Amazing Grace.”

He also influenced abolitionists like Hannah More and William Wilberforce. Britain passed the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act on March 25, 1807. Newton died that same year on December 21. Over 200 years later, Newton is remembered for his fight against the slave trade. His hymns are sung worldwide, and his legacy lives on.—Aubrynn Whitted, from our Torchlighters website. CH

By E. Beatrice Batson, J. D. Walsh, Aubrynn Whitted

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #150 in 2024]

E. Beatrice Batson (1920–2019) was emerita professor of English at Wheaton College (Illinois). J. D. Walsh (1927–2022) was emeritus fellow in history at Jesus College, Oxford. Aubrynn Whitted interned with CH and is a writer, a freelance editor, and an administrator at Christian Counseling & Education Foundation.Next articles

The golden age of hymns

Songs that spoke the language of Christian faith and aspiration

Vinita Hampton WrightFounding fathers

An innovative evangelist, a Christ-based preacher, and a pioneer missionary

James E. Johnson, Patricia Stallings Kruppa, Timothy GeorgeSurprised by Christ

Three spirits conquered by Christ

Lyle W. Dorsett, Matt Forster, Kaylena RadcliffSupport us

Christian History Institute (CHI) is a non-profit Pennsylvania corporation founded in 1982. Your donations support the continuation of this ministry

Donate